Are you a scribbler? Do you regularly commit your thoughts by putting pen to paper? Or does that sound a ridiculously old fashioned notion in this age of social media? On the other hand, perhaps you keep a handwritten diary, or you make your own ‘to do’ lists, or you may find yourself ‘doodling’ during a long work meeting...

Fortunately – for historians – several post-war Prime Ministers have been ‘scribblers’ in their official capacity, and their handiwork in the Prime Minister’s Office (PREM) files held at The National Archives, can make for fascinating reading. Comments written in the Prime Minister’s own hand (‘marginalia’) can be very revealing about the personality and guiding principles and values of a PM. Consider the following example from Margaret Thatcher’s first premiership.

Home truths

In a file concerning expenditure on government accommodation1, we learn that, in June 1979, following a Parliamentary written question about the costs of refurbishing accommodation for ministers, the Department of the Environment published a breakdown of spend for each of the government departments without consulting the Prime Minister’s office. An official in Thatcher’s office appears sceptical of the alleged costs for refurbishing Number 10, stating ‘I find these figures impossible to believe’. Thatcher voices her agreement writing 'So do I!'. Referring to the flat at No.10, the cost for bedding is queried with Thatcher noting “we use only one bedroom”, and that she can use her own crockery and the price of an ironing board prompts her to state, more than once, “I will pay for the ironing board”.

It’s an amusing example (on its release the press dubbed Margaret Thatcher the ‘Ironing Lady’), but it’s also a powerful illustration of Mrs Thatcher’s values, which are rooted in her strict upbringing - an emphasis on personal responsibility, thrift, self-reliance, and an instinctive antipathy towards unnecessary expenditure of tax-payers money – and this approach did not stop at home – it was an essential part of her government’s strategy in the early 1980s.

Forthright comments

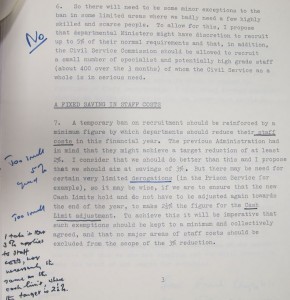

More hard evidence of the ‘Thatcherite’ approach can be found in a file entitled ‘Freeze on Civil Service manpower; action to reduce Civil Service numbers and staff costs’2. On a draft paper for Cabinet, by the Lord President, Christopher Soames, we see comments by Mrs Thatcher written in the margins made by her own hand. These comments are very direct – when Lord Soames suggested ‘some minor exceptions to the ban’ [on recruitment], Mrs Thatcher simply and emphatically, using her blue felt tip pen, wrote ‘No’. When he suggests a reduction of Civil Service staff cost of 3%, Mrs Thatcher wrote ‘Too small’, and gave her preferred figure of 5%. We can also see, from studying the documents, that Mrs Thatcher frequently underlined particular sentences or phrases which she found significant in memos - evidence of intense concentration on the details of the subject in hand.

Many of Lady Thatcher’s personal papers are available online at the Margaret Thatcher Foundation website, and are also rich in marginalia. The original personal papers are held by the Churchill Archives Centre.

All kinds of everything

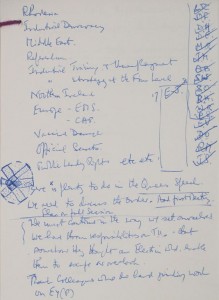

The next example shows the huge pressures to which Prime Ministers are subjected – it’s from a file entitled ‘Forward Look’3. In the autumn of 1978, the Labour Government were exploring key policy areas for the term ahead (James Callaghan had decided against an October general election). The file contains 23 pages of handwritten notes made by Callaghan during a meeting on future policy initiatives on 19 September 1978. The notes reflect a virtual ‘A-Z’ of government activity: devolution, educational standards, fuel costs, immigration, inner cities, law and order, pollution, public expenditure, unemployment, technological change...the list goes on and on. It is almost breathtaking in its scope – the longest ‘to do’ list ever?

True feelings

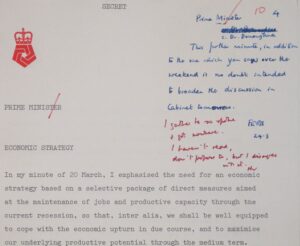

The Prime Ministers’ marginalia can include comments of astounding frankness concerning papers produced by ministerial colleagues. Prime Ministers could afford to reveal their true feelings when commenting on such papers as they were aware that they would not see the light of day for 30 years, and that they could rely on their private secretaries to convey their opinions and decisions in a polite fashion. In 1975 all the economic indicators were pointing the wrong way. The government was wrestling with rampant inflation, unemployment, and a balance of payments deficit. Chancellor Denis Healey’s strategy was to trim public expenditure and to keep wage increases in line with prices.

Tony Benn, Secretary of State for Industry, urged PM Harold Wilson to adopt an alternative, protectionist strategy, calling for direct intervention such as import restrictions, high tariff barriers and selective aid to industry. On 24 March 1975 he sent Wilson a memo reiterating the need for an alternative approach to the nation’s problems. Wilson’s terse comment on this memo was a model of conciseness: ‘I haven’t read, don’t propose to, but I disagree with it’4

As we’ve seen from this selection of choice examples, the marginalia in the Prime Minister’s Office files held by The National Archives are fascinating as they often include comments which can be very revealing about a PM’s reactions to memoranda and letters, giving insights into their approach to the job, personal style and aspects of personality – reflecting the human side to national leaders who were often under great pressure. When you see the handwritten comments of Prime Ministers, you are connected with the person and how they are feeling at that moment in time.

The digital challenge

The public records released each year by TNA under the 30 year rule - which will, in due course, reduce to 20 years – are in paper format and are likely to continue to be so for a good many years to come; but at some point they will become predominantly digital. Will email and social media formats be as revealing as paper files when historians of the future come to appraise them? These formats will certainly offer something different. Archivists have been grappling with the challenges posed by digital records for some time now; and increasingly historians are reflecting on this matter as well. Is the pen mightiest? Only time will tell.

Further information

Learn more about Past Prime Ministers on GOV.UK

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.

Suggested further reading

Robert Blake, The Office of Prime Minister (1975)

Vernon Bogdanor, From New Jerusalem to New Labour: British Prime Ministers from Attlee to Blair (2000)

Peter Hennessy, The Prime Minister: The Office and its Holders since 1945 (2000)

6 comments

Comment by Archer posted on

Interesting and revealing.

Comment by Sam posted on

I'm impressed by the new history available on the .Gov blog. It makes information easily accessible and is demonstrated in an educational fashion.

Hats off to whom ever thought this idea up.

Comment by nal posted on

wow

Comment by Graham Francis posted on

A friend of mine has printed out the picture of James Callaghan's to-do list ("middle east. referendum") and has put it beside her computer at work - to give her a bit of perspective when it's needed...

Comment by Simon Fowler posted on

As might be expected Clem Attlee's comments were terse. Generally he just writes 'I Agree' or even 'yes', but occasionally there is more, which can present problems to modern historians as his handwriting was truly awful. But best of all he was a compulsive doodler so researchers can sometimes find intricate doodles in his papers at The National Archives (series PREM 8).

Comment by google posted on

Every weekend i used to visit this site, for

the reason that i want enjoyment, as this this web page conations actually good funny stuff too.