The early Exchequer was once described as an occasion not an institution, referring to the somewhat ad hoc nature of its foundation and early days. Over 9 centuries later, the modern Exchequer retains a similar place in our national consciousness – once a year the Chancellor holds up a battered red despatch box outside No.11 Downing Street for photographers, before delivering his budget speech to the House of Commons. The first Exchequer budget was prepared in 1284; it did not balance and showed that the Crown was spending far more than it could possibly bring in, hence the rapid introduction of taxation to cover the shortfall.

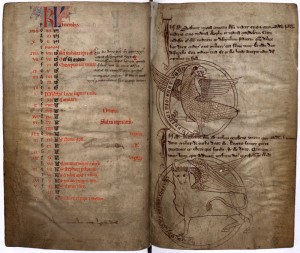

(Facsimiles of Irish Manuscripts, volume III, plate xxxvii.)

The origins of the Exchequer

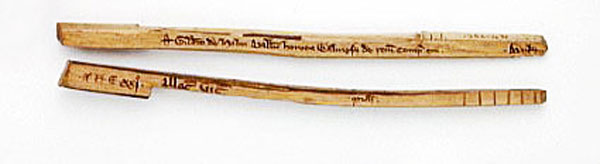

The Exchequer’s rather unusual name was derived from the chequered cloth on which the confrontational audit process took place between the powerful Barons of the upper Exchequer and the hapless accountants summoned before them, who were regularly interrogated about the state of their accounts. The cloth was used to visually record the sums of money that were demanded and received, and an accountant was only discharged of their debt on the provision of evidence – a writ authorising expenditure on behalf of the Crown, or a wooden tally denoting that a payment had been made into the lower Exchequer. All these transactions were then carefully recorded on parchment rolls.

We know a great deal about the 12th century Exchequer thanks to the Dialogus de Scaccario, an intimate (if somewhat self-important) account written by royal treasurer Richard fitz Nigel. The Exchequer started life as an expedient means by which the King could manage his financial affairs without actually being present – government by proxy through appointed officials – which was particularly important given Henry II and his sons spent most of their time abroad fighting over their continental possessions.

An ancient archive full of wonders

Although its main task was to ensure every penny was collected and accounted for, the Exchequer was always more than just a breeding ground for medieval accountants - it was seen as a place of receipt for written records as well as money. Its own formidable archive include not only the longest consecutive set of public records, the Pipe Rolls (from 1155 to 1832 though admittedly of limited use for the last few centuries) – but also treasures such as Domesday book, royal wills and the various chests that were used to house them. Indeed, it was an ill-judged attempt to burn superfluous wooden tally sticks (used for recoding payments) that saw the Houses of Parliament consumed by fire in 1834.

Other functions included acting as a court of law – the Exchequer of Pleas – whilst it also played a key role in the management of royal lands, especially via the special revenue courts that appeared after the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Decline and fall

Nevertheless, the bureaucratic procedures that had been the Exchequer’s core strength were increasingly viewed as a hindrance to the speedy process of government, and such was the disillusionment with Exchequer protocol by the fifteenth century that it was decreed in Richard III’s time that:

‘The Court of Exchequer be clearly dismissed and discharged from any meddling with any foreign livelihood in taking of accounts, as Wales, Duchies of Cornwall, York or Norfolk, Earldoms of Chester, March, Warwick, Salisbury and of all other lands being in the King’s hands by reason of forfeiture’.

The Audit Office subsequently emerged, and the Exchequer's remaining work was increasingly eclipsed by the Treasury in the 17th century, though aspects of Government business continued to be discussed and recorded in the Exchequer. However, the 19th century saw further reform and the Exchequer's function as a financial department of state formally ended in 1833.

All that remains today is the honorific post of the Queen's Remembrancer, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer (now part of the Treasury Board) - plus an unparalleled set of records that reflect the richness and diversity of life from the middle ages to the Victorian era which can be consulted at The National Archives at Kew.

Related post

'Follow the money': The Treasury

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.