Britain’s involvement in the Second World War began at 11am on 3 September 1939. The declaration came after eleven days of mounting international tension and was just one part of a flurry of governmental activity. Over three million people had already been evacuated, five million posters had been printed, 15 million ration books awaited delivery, thousands of temporary civil servants had been employed, and a handful of new government departments were ready to organise life on what was referred to as the ‘Home Front’.

The Ministry of Information was among the most high profile of these new departments. The Ministry was in many ways an unprecedented experiment in the British government’s control of communication. It was designed as ‘the centre for the distribution of all information concerning the war’. This meant that, unlike its First World War namesake, it would be responsible for both the issue and censorship of news.

Censorship in the Second World War

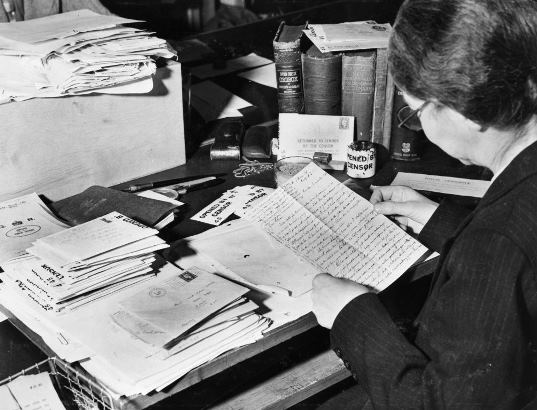

Press censorship in the Second World War worked on a principle of self-enforcement. Newspapers were issued with guidance about topics that were subject to censorship and invited to submit any story that might be covered by these so-called ‘Defence Notices’. Submitted stories would be scrutinised by the censor and redacted in accordance with the guidelines. Any information of potential military significance – from weather reports, to the exact location of troops – would be removed.

If a story were suitable for publication, it would be returned to the newspaper bearing an official stamp, with any changes marked in blue pencil. Any story that was not ‘Passed for Censorship’ was liable for prosecution if it were found to contravene the guidelines. Reports directly issued by the Ministry of Information were censored before release.

The system was designed to strike a balance between press freedom and national security. But it was only a week before it came to the brink of collapse. This was a result of a chaotic attempt to apply retrospective censorship to news about the arrival of the British Expeditionary Force in France. Subsequent events led to a crisis in government, stoked press hostility, and threatened the very existence of the Ministry of Information.

The Story Breaks

The crisis began at midday on Monday 11 September when an official broadcast in Paris wrongly announced that British troops were engaged in offensive action against Nazi forces. The claim was subsequently repeated in a second broadcast by the French author Roland Dorgeles. Before long, it had been cabled to the USA and spread worldwide by the United Press and Reuters press agencies.

In London, where news about the British Expeditionary Force had been subject to a D-Notice since the first landings on 4 September, officials in the Ministry of Information concluded that any military value in the news had been lost. And so they wrote to the War Office requesting that reports about the existence of British troops in France should be released.

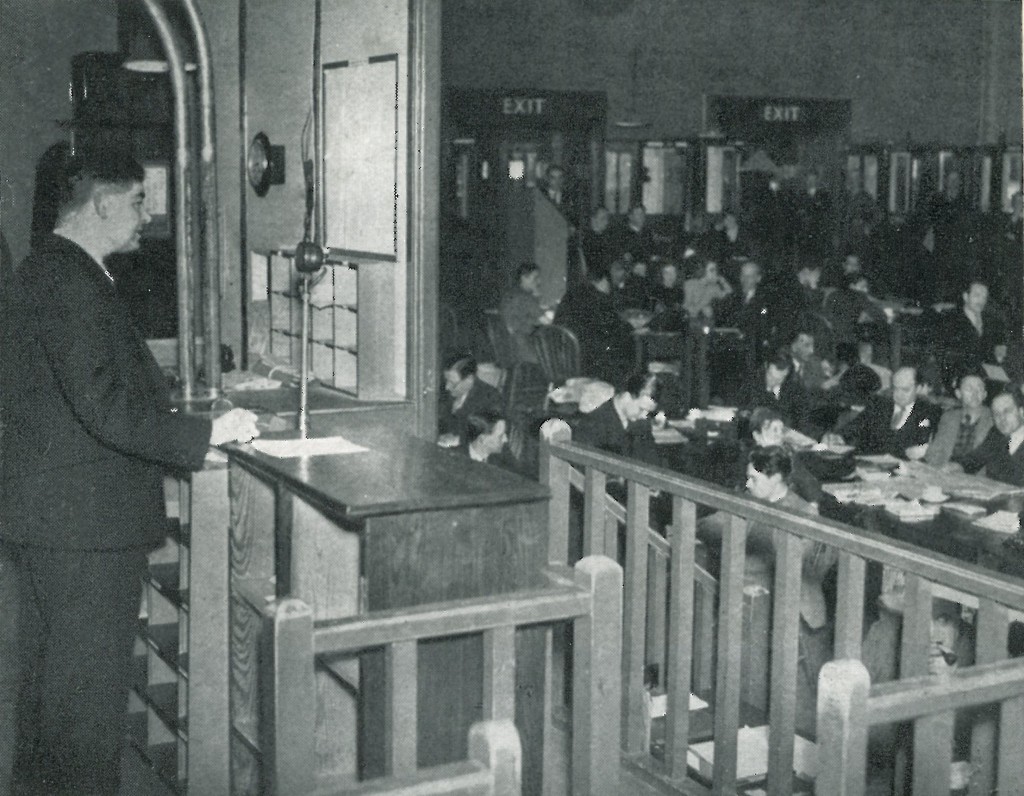

It was 9pm before the War Office confirmed to the Chief Censor that the story could be released and 9.40pm before the decision was transmitted to the Ministry of Information’s Press Room. With the assembled journalists anxious to make their morning editions, many decided to submit drafts that had been prepared from the press agency reports of Dorgeles broadcast. These reports included the claim that British troops were engaged in active combat. Because the Censorship Division was under strict orders to confine the news to the bare fact that troops had arrived in France, all such reports were passed back to the War Office for further vetting. Their contents caused the military authorities considerable worry.

From Censorship to Chaos

Leslie Hore-Belisha, the Secretary of State for War, was informed of the situation within an hour of the first reports reaching the War Office. He held an emergency telephone conversation with the Ministry of Information’s Deputy Director at 11pm but was unconvinced by the Ministry’s assurances. Fearing that the censors would not be able to protect vital information from leaking out, Hore-Belisha decided that the War Office would re-impose its original ban on the news at 11.30pm.

This decision forced the Ministry of Information to make a desperate request for retrospective self-censorship. It was explained that the previous decision was void and that any such mention could result in prosecution. Indeed ‘All possible steps’ would be taken to protect ‘the national interest’.

The Ministry was certain that editors would alter their front pages to ensure compliance with the new ruling. The Home Office, which had been contacted directly by Hore-Belisha, was not so sure and one unnamed senior official decided additional measures were necessary. Scotland Yard were instructed to arrange the seizure of all newspapers, police officers were deployed to newspaper offices and wholesale newsagents throughout Britain, roadblocks were erected in Fleet Street, and newspaper trains were stopped en route from London. The situation was widely described as one of ‘chaos’ and ‘complete confusion’.

The Ministry of Information continued to petition the War Office but their pleas were ignored. Things became almost farcical when the Ministry’s French equivalent (the Commissariat Génèral à l’Information) released additional information about the British troops in the early hours of 12 September. This led to a second change of heart in the War Office and the ban was finally lifted at 2.55am. However, the decision came too late for some newspapers to include the story in their early editions, and many papers were delivered hours late on the morning of Tuesday 12 September.

Implications

The events of 11-12 September led to a storm of criticism in the press. An editorial in the Daily Mirror attacked ‘muddle-headed bureaucrats’ and accused the government of acting in a ‘true Gestapo manner’. The Daily Mail pointed out that ‘all of the details originally given were originally passed by Ministry of Information censors’ and claimed that some had been ‘suggested by Ministry officials’. This theme was continued by the Daily Express which singled out Hore-Belisha for blame.

The situation became more serious when Francis Williams, the editor of the Daily Herald, pressed the opposition Labour Party to find out why he had been woken at 1.45am to be told that the police had seized control of his office. The parliamentary debate held on Wednesday 13 September served to shift the blame back onto the Ministry of Information. This changed the nature of debate within government and the Ministry came under pressure to undertake radical reform.

After two weeks of further criticism, it was decided that the current system was broken beyond repair. The Ministry of Information’s responsibility for issuing and censoring news was duly removed on 9 October 1939 and passed to an independent Press and Censorship Bureau. This episode brought the Ministry to the brink of collapse and necessitated a lengthy process of rebuilding that was not completed until 1942.

This was a defining moment in the British government’s relationship with the press. It is one of many rich examples in The National Archives that illustrate the challenge of war for an open society.

Further Reading

The Ministry of Information is the subject of a major AHRC-funded research project being undertaken by the School of Advanced Study in collaboration with The National Archives and the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College London.

You can find out more at http://www.moidigital.ac.uk

See also:

Ian McLaine, Ministry of Morale: Home Front Morale and the Ministry of Information in World War II (London: Allen & Unwin, 1979)

Robert Mackay, Half the Battle: Civilian Morale in Britain during the Second World War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002)

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.

2 comments

Comment by Gerard J. de Boer posted on

Can you tell me where censor 5111 was located ? I have several envelopes from 1948 with his marking. Is there a book that lists those locations in Germany ? Thasnk you much,

Gerard J. de Boer

Gjdeboer@omsoft.com

Comment by Henry Irving posted on

I'm afraid that I've not found any such list. Postal censorship was organised separately from press censorship so has not been part of my project's focus. Good luck with your own search!