Today's release of Prime Minister’s Office records and Cabinet Papers from 1985-1986 covers the mid-point of the Thatcher premiership. If this period is beyond your living memory, you might be tempted to think that the files would reflect the Thatcher revolution at full steam. The Conservatives had won two general election victories (1979 and 1983) and the Miners’ strike had been defeated. During the mid-eighties, ‘yuppies’ were becoming a cultural phenomenon, and disposable incomes for many were beginning to rise. However, the files reveal that this period was far from being ‘plain sailing’ for the government.

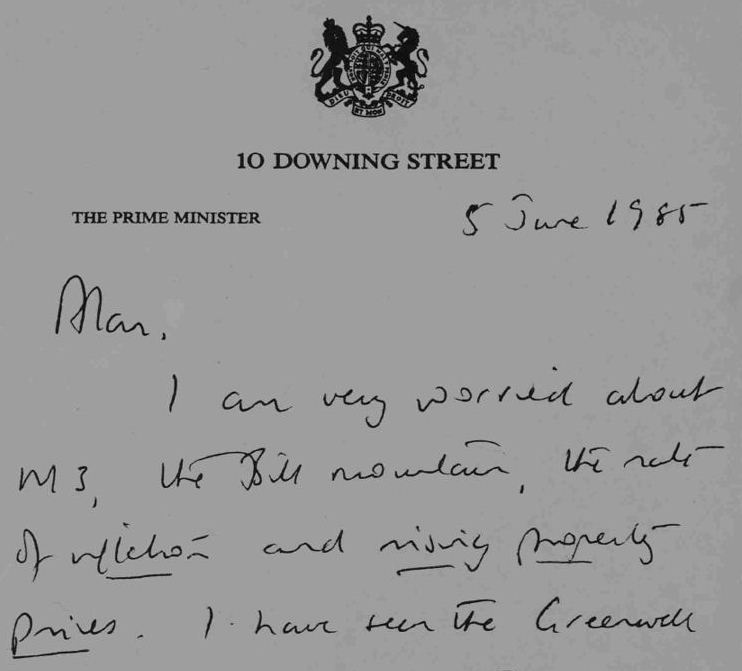

The Westland crisis, which Michael Heseltine described as ‘the complete breakdown of Cabinet Government’1 attracted a great deal of media attention during late 1985 and early 1986. Taking a wider perspective on these years, the files show that there was a great deal of concern, expressed by advisers, Treasury officials, Cabinet ministers, and the Prime Minister herself about losing control – of public expenditure, inflation, and the money supply; as well as concerns about high interest rates, sterling crises, a credit boom and an unemployment level which remained stubbornly high. These concerns are shown most graphically by Mrs Thatcher’s marginalia in the Prime Minister’s Office files, for example, on a memo from Professor Alan Walters dated 4 June 1985 about ‘monetary control’, Thatcher writes: ‘I had no idea we had let things go to such an extent’ and the next day she replies to Walters in a handwritten note: ‘I am very worried about M3, the Bill mountain, the rate of inflation and rising property prices’2.

Catching the Prime Minister’s eye

Many of the problems the government were wrestling with have a very familiar ring, and have resonance for today, particularly the need to control public expenditure. Some of the most outspoken comments originate from advisers, such as David Willetts (of the Policy Unit): ‘it really is pretty pathetic that Government running costs have risen faster than inflation every year since 1980’3. After a rise in interest rates in January 1985 John Redwood (Head of the Policy Unit) writes: ‘we need to use this period of gloom and doom to sharpen the knives on public expenditure’4. Advisers such as David Willetts and John Redwood consistently write memos in a very direct style, making arresting statements in order to catch the Prime Minister’s eye, so that their papers stand out in the huge flow of paperwork which crosses the Prime Minister’s desk.

Under the annual Public Expenditure Survey (PES), public expenditure was decided through negotiations between individual departments and the Treasury, with the Prime Minister becoming more involved during the later stages, and with final recourse to a Cabinet Committee, the ‘Star Chamber’ to decide on the most difficult cases. As more and more files are released from the 1980s, we see the problematic nature of the PES process, with Departmental ministers frequently pleading their case for no further cuts, as the deadline for settlement approaches.

Colourful language

Bernard Ingham, No.10’s Chief Press Secretary, using typically colourful language, writes that the PES exercise ‘has built into it levels of conciliation and (increasingly) degrees of bloodletting on the Government, or No. 10 carpet, which, to mix metaphors, is meat and drink to the media’. He asks: ‘can we drastically shorten the Government shooting season?’5. Responding to this, Robin Butler, Principal Private Secretary, discusses the possibility of bringing together decisions about expenditure and taxes – which might help – but he says such a move would be fraught with difficulties. The files show that worries about public expenditure levels extended into 1986. Following a series of spending ‘overbids’ by Ministers, Chancellor Nigel Lawson tells the Prime Minister in July 1986 ‘‘I believe we are not far from creating the impression that in the run-up to the next Election we are throwing all restraint on public expenditure to the winds’6.

The mid-eighties saw a debate about the ‘death of monetarism’, and the newly released files touch on this. The difficulties of targeting the growth of the money supply were becoming increasingly apparent, and the Chancellor preferred to concentrate on the sterling exchange rate as the key monetary indicator. Increasingly Lawson advocated the benefits of joining the European Rate Mechanism, partly as a means of encouraging financial discipline. Again, John Redwood’s advice to the Prime Minister on this subject was very clear: we should ‘drop all reference to the EMS [European Monetary System] at all’7. Mrs Thatcher’s scepticism about this financial system kept Britain out of the ERM until October 1990.

Recurring themes

Any researcher exploring modern public records will soon discover that there are certain recurring themes in modern British history – and will be struck by how the patterns of the past reflect the present. For example, following the collapse of Johnson Matthey Bankers in 1984, and against the background of the deregulation of the stock exchange (the ‘big bang’), the files show that there was a great deal of concern about the issue of banking supervision in 1985-86. On 6 November 1986 David Norgrove of the Policy Unit writes to Rachel Lomax of the Treasury: ‘the Prime Minister has asked whether the Treasury and other relevant departments are confident that the arrangements now being put in place for supervision of banks, other financial institutions, brokers, conglomerates, etc., are comprehensive’8. Nigel Lawson was making the first moves towards a more rigorous system of banking supervision at this time, moves which resulted in the Banking Act of 1987.

Having looked through many bulging files documenting the Government’s economic policies in the mid-eighties, I am left with an overriding impression of the sheer complexity of the roles of Prime Minister and Chancellor, particularly in the highly technical fields of economics and state finance. Many worries or concerns are expressed about losing control of economic forces, and there is closely argued debate about ‘which levers to pull’, for example, the vexed question of whether interest rate levels should be increased in order to dampen down the demand for credit. This particular responsibility was removed when the Government allowed the Bank of England to set domestic interest rates from 1997 onwards, when the Bank was granted operational independence – but the burdens on those in the ‘core executive’ remained heavy, and these obviously included the full range of political, diplomatic and social issues as well as economic . Those at the very heart of government may enjoy a huge range of powers, but these roles carry unenviable responsibilities – and this is reflected in the fascinating and revealing marginalia and other notes within governmental files. With many of the issues highlighted in the files from 1985 and 1986 sounding very familiar thirty years on, the release shows the value of archives in providing insight into the complex deliberations behind the scenes, offering lessons for the future.

Other stories from the 1985-86 releases include: the Government’s policy on chemical weapons, the defection of KGB Officer Oleg Gordievsky, a series of heated exchanges between the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition, and some issues associated with football hooliganism.

See The National Archives website for more details

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.