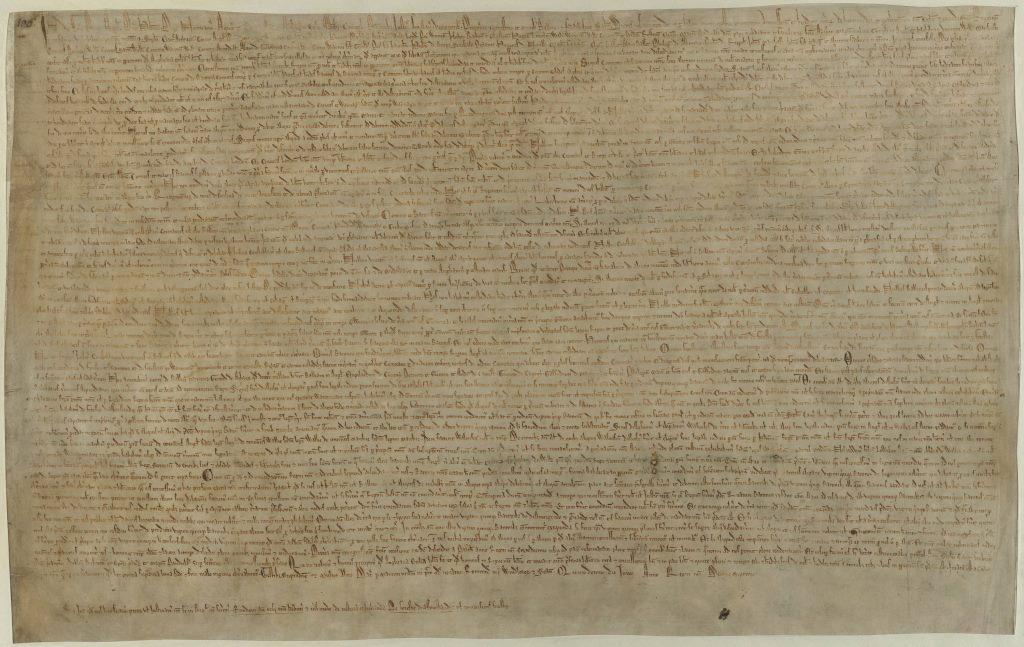

This year marks the 800th anniversary of the granting of Magna Carta by King John. Today, the Great Charter is viewed as the foundation of many of our rights and liberties and throughout the year there are commemorations, exhibitions and activities around the anniversary, as well as lots of new books, online resources and TV and radio programmes on the subject.

This anniversary is one of the reasons that 2015 has been designated as the year for celebrating ‘Parliament in the Making’ so in this blog I am going to focus in particular on the clauses of Magna Carta that relate to the emergence of Parliament as an institution. This also fits in with my earlier blog on Simon de Montfort’s historic Parliament in 1265.

Medieval councils and counsel

Medieval kings were expected to consult with and take advice from the leading churchmen and nobility of their kingdoms. The greater nobility were generally tied to the king through bonds of kinship, ancestry and tenure – in post-Conquest feudal society the king’s tenants-in-chief held their lands of the king. They were considered natural leaders of the kingdom with both a right and an obligation to give counsel to the king. Their meetings were mostly frequently referred to as ‘councils’, although in the reign of Henry II we do see some early use of the French term ‘parlement’ to describe a royal council. Whatever they were called, these councils were far from the representative Parliament that we have today. Neither, though, were they mere facades. Kings wanted counsel and took the advice they received seriously – and there was no particular remit of the council. Henry II, King John’s father, was a king who consulted a great deal with his magnates, and the frequent absences of Richard I, John’s older brother, during his reign meant a further expansion of the role of the council.

The impact of taxation

Over the course of the 12th century though, it had become customary that general taxation should not be levied without the counsel of the barons. This process started with the taxations imposed by Henry II to pay towards the needs of the crusader states in the Holy Land. Before this point, barons were expected to pay towards certain ‘feudal incidents’ – such as to raise money for the marriage of the king’s daughter – but the overall burden of tax upon them was rarely large. Royal government did raise money through ‘geld’, a direct tax, but this ceased to be imposed after 1162.

But as new taxes were imposed to pay towards the crusader states, the burden of tax fell more heavily upon the baronial class, and so developed the custom that its counsel would be sought – with the implication that it would consent. On a purely practical basis, the need for counsel doubtless also reflected the fact that in order to collect taxes from across his kingdom, the king relied on local networks, making it vital that he had the support of those barons who had great power in their own localities.

King John’s approach to counsel

As mentioned, the reign of Richard I, with that king’s long periods of absence, had resulted in an expansion of the role and importance of the king’s council. King John, however, was a very different sort of king. From the very beginning of his reign, John was accused by contemporary chroniclers of listening to ‘evil counsel’ and ‘familiar counsel’ – the latter suggesting that he listened to his own friends and confidantes but overlooked the advice of the wider baronial community. Even worse, in the eyes of the traditional nobility, was the fact that many of John’s confidantes were ‘new men’ from outside the elite and often indeed from outside England. He was also restless and frequently on the move, taking advice from those around him; those barons who were not usually in his retinue doubtless felt sidelined.

Of course, the situation was far from clear cut. John did hold great council meetings and not all of his friends and close counsellors were arrivistes on the English political scene. Further, as John Maddicott points out ‘notions of proper counsel were a matter of unstated conventions, as yet too shapeless and amorphous to be easily codified’. Contemporary commentators could identify ‘evil counsel’, but that is not to say that it would have been easy for anyone to define exactly what ‘good counsel’ ought to look like.

Nonetheless, it was clear that John was not adhering to the conventions of seeking counsel that had been developing. In 1207, he levied a great tax on the kingdom. The tax was imposed at a great council, held in Oxford, but the evidence suggests that limited notice was given of the occasion and that the council itself lasted only a day and half. All of this rather implies that John was managing events to ensure limited attendance with no time for proper debate.

Magna Carta – codifying how to seek counsel

This sort of behaviour helped to crystallise ideas of the occasions on and means by which the king should seek counsel. This is illustrated in Magna Carta, issued a few years later, in which we see the beginnings of attempts to codify the ways in which the king should seek advice. The dominant theme is taxation: clause 12 of the Charter lays down that ‘no scutage or aid is to be levied in our kingdom, save by the common counsel of our kingdom’. Scutage was the fee that a tenant in chief could pay to the king in lieu of providing military service; aid could refer to specific feudal obligations but could also mean general taxes. Only three exceptions were specified: the king could levy aid with counsel for ‘the ransoming of his body, and the making of our first born son a knight, and for the marrying a single time of our first born daughter’, all incidents for which a king could traditionally expect to levy aid from his kingdom.

Clause 14 outlines how this ‘common counsel’ must be gained: the king would summon the leading churchmen and barons to meet at a specified time and place, with at least 40 days’ warning. This would mean that there was plenty of time for the barons to assemble – addressing the issue that John’s very mobile court had made settled councils infrequent. It was a two-tier system – the ‘greater’ men were to be summoned individually; all the other tenants in chief would get a general summons via the royal officials. In total, this could have amounted to hundreds of people. In addition, the king would ‘express the cause of the summons’ – so that those attending would know in advance what was on the agenda. This was no doubt a direct response to John’s attempts to impose taxation with the minimum of consultation earlier in his reign.

Clearly the councils outlined in these clauses are a very long way from what we would now consider a Parliament. Further, Magna Carta was primarily codifying what was already customary. This was no radical departure from traditional methods of rule. Nonetheless, Magna Carta was issued in direct response to the grievances and concerns of John’s barons; the fact that it engages so closely with the issue of how and why royal government should seek counsel shows how important this issue was, and how thinking around it was developing. The idea of the ‘common counsel of our kingdom’ shows that the barons were thinking of themselves as the embodiment of the community of the realm. While these clauses only deal with taxation, it is hard to believe that the barons did not see beyond this to a system of government in which their views on wider issues would be taken into account as a matter of course. Further, they were attempting to impose some kind of routine on the methods by which counsel was sought and given, ensuring that there was sufficient time for them to assemble and discuss. Magna Carta certainly did not ‘invent’ Parliament, but it was a small but important step for Parliament in the making.

If you are interested in Magna Carta, its place in history and its role in the development of ideas about freedom and democracy, don’t miss the exhibition Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy which is at the British Library until 1 September. See the British Library website for further information.

Suggestions for further reading:

J.R. Maddicott, The origins of the English parliament, 924-1327 (Oxford, 2010).

D.A. Carpenter, Magna Carta (London, 2015).

J.C. Holt, Magna Carta (2nd edn., Cambridge, 1992).

Nicholas Vincent, Magna Carta, The Foundation of Freedom (Third Millenium, 2015).

See also the excellent commentaries on these clauses on the website of the Magna Carta Project

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.