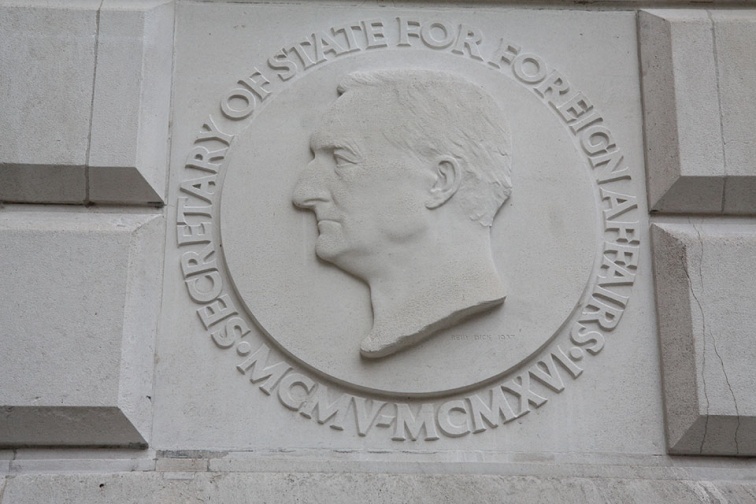

For almost 80 years the distinguished profile of Sir Edward Grey has looked on as the great and the good have made their way in and out of the ‘Ambassador’s Entrance’ of the Foreign Office. But how did this memorial to Britain’s longest continuously serving Foreign Secretary come to be there?

Grey was in office from 1905 to 1916 and is chiefly remembered for being Foreign Secretary when Britain entered the First World War in 1914. Created Viscount Grey of Fallodon in 1916, he died on 7 September 1933. Soon after his death a committee was formed to devise a fitting tribute to keep alive his memory as a statesman and public figure.

Their initial plan, for a memorial in the precincts of either Westminster Abbey or the Palace of Westminster, was dashed by a new rule which barred such memorials until ten years after a person’s death. So the committee proposed a bust of Grey, in Italian stone within an architectural surround of Portland stone, to sit in the Downing Street Garden wall facing the Foreign Office.

But the First Commissioner of Works, the minister responsible for overseeing the erection of public memorials in London, disliked the scheme. As an alternative he proposed a medallion, featuring Grey’s profile, along with a suitable inscription, to be placed on the Downing Street wall of the Foreign Office. Meanwhile the Foreign Office preferred to see a bust of Grey placed in a ‘suitable niche’ on the Grand Staircase.

When the issue came before the Cabinet in July 1935 they favoured the Foreign Office option.

However the committee thought that the memorial had to be accessible to the public, given the fact that it was being paid for by public subscription, and instead pushed for the medallion in the Foreign Office wall. There was some confusion as to whether this option had already been rejected by the Cabinet. (In fact they had remained silent on the point.)

The First Commissioner wrote to the Prime Minister and the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, to recommend the proposal. Eden strongly opposed the medallion which he thought would be unsatisfactory from an aesthetic point of view. He pressed again for a bust on the Grand Staircase, opposite statues of other former Foreign Secretaries, where it would be seen by the majority of visitors to the Foreign Office and where Grey would be ‘in good company’.

When the First Commissioner met the committee in February 1936 he had before him a letter from the Prime Minister agreeing to the scheme and a letter from the Foreign Secretary strongly opposing it. The First Commissioner deferred to the Prime Minister. Eden, who thought it absurd that the Foreign Office had no power to control memorials ‘about its walls’ called it ‘a wretched business’.

In July 1936 Sir Edwin Lutyens submitted a scheme consisting of a portrait panel set into the masonry at the side of the Foreign Office doorway at the end of Downing Street with an inscription cut into the stone base below. The plans were sent to the Royal Fine Art Commission to see if their comments might provide an opportunity to cancel the offer of the site but they replied positively. Eden subsequently dropped his objections.

On Tuesday 27 April 1937 the memorial was unveiled by Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin in front of a distinguished company of friends and admirers of Lord Grey. Over 1,000 people had subscribed to the fund, raising over £4,000 for the memorial and other commemorative projects.

(The Times / News Syndication)

The plaque consisted of a classical portrait of Grey, in relief, surrounded by a circular inscription: ‘Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, MCMV—MCMXVI’. Carved in the wall below the plaque, after Grey’s name and dates, was the following tribute: ‘By uprightness of character, wisdom in council and firmness in action, he won the confidence of his countrymen, and helped to carry them through many and great dangers’.

Despite the differences of opinion the choice of memorial has stood the test of time. The plaque’s location, next to the door used for eleven years by Grey to enter the Foreign Office, proved appropriate, even though Downing Street is now closed to the public.

But decades of weathering eventually took their toll. Until recently it was in a poor state of repair, with parts of the inscription hardly legible. In 2014, the year of the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office restored the memorial to its former glory. It now forms an intrinsic part of the fabric of the building.

For more on how the memorial came to be built see: http://issuu.com/fcohistorians/docs/fco896_gray_memorial_booklet_-_web_812e11dc3c95ff

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.