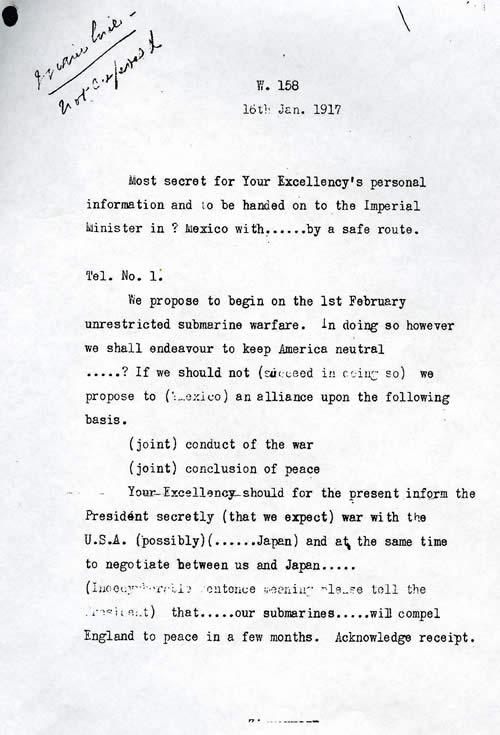

A 100 hundred years ago today the German Foreign Minister, Arthur Zimmermann, sent a telegram that was to have profound consequences for the course of the First World War.

At the beginning of 1917 American opinion was anti-German, and largely in favour of Britain and her allies. However, this bias was tempered by British efforts to block trade with Germany. Neutrality was still important to the United States at this point - it was the platform on which President Woodrow Wilson was re-elected in November 1916. Britain was actively trying to influence America in favour of entering the war on the Allied side, and Germany was conscious of the risks that US entry to the war would pose. Nevertheless, owing to the effect of the Allied blockade combined with a poor harvest, Germany felt forced to take drastic action, including the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare on 1 February 1917. This policy was bound to antagonise the Americans.

It was for this reason that, on 16 January 1917 Zimmermann sent a pre-emptive telegram to the Mexican Government. It indicated that the new policy on submarine warfare might bring Germany and the USA into conflict, and asked if, in such an event, Mexico would be willing to fight on the German side. In order to 'sweeten the deal', Zimmerman suggested that Mexico would get back her lost territories in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona when Germany won the war.

Dilemma for British Naval Intelligence

The proposal, which built on poor US- Mexican relations, was refused. Unbeknown to Germany, British Naval Intelligence had intercepted the telegram and deciphered it. Whilst the British authorities wanted to pass this information to the Americans, to do so would reveal that communications were being intercepted. The Americans would not appreciate the thought that their signals might also be collected. If the Germans then became aware of this and changed their codes, the intelligence advantage would be lost. Only when the Admiralty found a solution to this was the decrypted telegram sent to the Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour.

The answer was that there were several copies of the telegram, with slightly different language. By handing over the decoded version sent via the German Embassy in Washington to Mexico, the British Government hoped to hide the fact that the message had been intercepted, so that it would appear that the document had been leaked in Mexico instead.

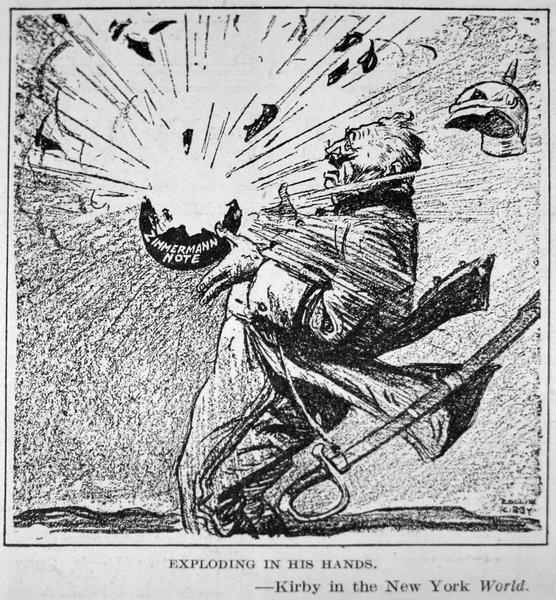

On 3 February, America broke off diplomatic relations with Germany following the German resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Although they did not declare war, the environment was now more receptive to change. On 24 February 1917 Britain released the message to President Wilson. Shortly afterwards reports of the telegram issued in the American press. Some believed that the telegram was Allied propaganda and a fake. The doubt ended when Zimmermann acknowledged authorship. The result was public outcry in the US. On April 2, 1917, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany, stating, ‘The world must be made safe for democracy,’and war was declared on Germany on 6 April. David Kahn, the cryptographic historian, has said that ‘No other single cryptanalysis has had such enormous consequences.’

Signals intelligence in the First World War

German naval and diplomatic communications were decoded by the Admiralty in Room 40, the centre of Naval Intelligence codebreaking in the First World War. The War Office had its own team dealing with signals intelligence, MO5b, later called MI1b. Deciphering German telegraphic traffic was a challenge that initially both teams worked on together. They separated in early November 1914 and it was in 1915 that Room 40 acquired responsibility for intercepting and decoding German diplomatic traffic. The biggest difference between the approach of the Admiralty and the War Office was that for the British Army most cryptology was in the field, whereas for the Admiralty it was centralised in Whitehall.

Despite several vital documents passing through it (both the Zimmermann telegram and the notice that the German fleet had sailed just prior to the Battle of Jutland), there are many mysterious elements about Room 40. Some key facts relating to its operation were forgotten or not clearly recorded. During the war secrecy about sources was considered more important than using the data. In particular there has been uncertainty and misinformation about the location of the room, about which there has been both speculation and mystery. There have been different theories about the source of the codebook used to decipher diplomatic traffic. Even today, some people raise the question of authenticity of the Zimmermann telegram.

Further reading

Nicholas Black: The British Naval Staff in the First World War, (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2009)

GCHQ, The story of signals intelligence 1914-2014,

Saul Kelly (2013): Room 47: The Persian Prelude to the Zimmermann Telegram, Cryptologia, 37:1, 11-50

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.