When governments communicate, the medium can be as valuable as the message. In the modern age of instant news and response through social media, it is often easy to lose sight of the importance of the method of interaction as well as the specific information being transmitted.

Language has always been key to effective communication. In 2014 the Government Digital Service announced clear guidelines for writing in plain English on government web pages. Accessible language in official information remains one of the main factors in encouraging the participation of citizens in the democratic process.

A focus on language and the methods by which the population hears about policy or receives important information is not a new concern of the Crown. Some previous landmarks in the official use of English required statutes. The 1362 Pleading in English Act permitted courtroom business to be done in English. The Anglo-Norman French normally used by judges and attorneys was not easily understood and left lay people confused about what happened in court. The written records of Common Law cases remained in Latin until the Proceedings in Court of Justice Act of 1730 required that English become both the language of pleadings and of the written record of cases in the law courts of the Untied Kingdom of Great Britain.

English documents created by the Crown

Documents written in English are found in the Crown’s archive during the medieval period but they are rare before the growing standardisation of written English by the Crown’s secretariat - the chancery – during Henry V’s reign (1413-22) [1]

Occasionally before that time, voices in English can be heard in records sent to the crown, such as vernacular petitions or legal records that captured direct speech. More difficult to locate are English documents created by the Crown itself. Where examples do occur, we can be sure that their creation was significant. One of the earliest deliberate post-Conquest uses of English by government dates from October 1258. It relates to the enforcement of the agreements known as the Provisions of Oxford, between King Henry III and the lords.[2]

Previous constitutional crises of Henry III’s reign had been managed by negotiation between the king and his ruling elites; often resulting in a re-issue of the Magna Carta of 1225. By the start of the 1250s, however, Henry was running out of chances to deliver previous commitments to uphold the clauses of the Great Charter. Henry III was mindful that his father, King John, had triggered a civil war in 1215 by rejecting earlier agreements.

Crises during Henry III’s reign

As a series of crises overstretched the capacities of Henry’s regime, he was in danger of repeating his father’s underestimation of the importance that the nation placed upon the rights and liberties recorded in the clauses of the Charter. Foreign war and an attempt to build support for a crusade left the king heavily in debt. Pressure to generate funds began to be felt throughout the country. Henry was also failing to keep the church happy as the privileges of clerics were squeezed to fill the Crown’s coffers. The 1255 uprising of Prince Llewellyn ap Gruffydd in Wales and confusion in England’s wider foreign policy drove the aristocratic lords into conflicting factions.

A sudden combination of war, harvest failure and a disintegration of King Henry’s relations with the church over papal taxes brought the crises to a head. In the spring of 1258, Henry summoned the lords and senior churchmen to parliament. To avoid pushing political opposition into armed rebellion, King Henry had to agree to be bound to the type of collaboration in government and guarantees over rights that were found in Magna Carta.

A group of nobles led by Simon de Montfort, earl of Leicester, forced the king to accept the advice of a council of fifteen barons. This council was to be elected from two groups of twelve men nominated by the barons and by the king. The Council of Fifteen would also elect the main officers of state and all would be accountable to parliament, which would meet three times each year. The Previsions also required that the conduct of local officers be investigated and monitored.

Since so much of the crown’s business passed through the sheriffs, much attention fell on how their role would be reformed.

Reaching ‘all the King’s subjects’

To publicise this agreement, in 1258, the Crown issued for the first time, official letters with the same text in Latin, French and English. This was a crucial moment in the government’s use of the English language to communicate in a way that could reach all citizens directly. The letters were addressed to ‘all the king’s subjects’ and not to named officials in the counties. Sheriffs or other officers would normally have received instructions in Latin writs or letters, often including a formal text that was to be the basis for proclamations. Staff in the sheriff’s office would translate, summarise or re-work that text into a vernacular form that could be proclaimed by criers at the sheriff’s court or other public gatherings such as markets. That process created an opportunity for the text to be presented in regional dialects that would connect directly with local communities. A system that allowed local officials discretion over how the crown’s instructions were transmitted within their own districts was flexible, but remained open to manipulation; especially when the conduct of sheriffs was an issue. The letters of 18 October 1258 were produced in English precisely because they concerned how the sheriffs behaved in representing the Crown and in upholding the reforms that had been imposed upon the king. Those documents were to be stored in the sheriffs’ treasuries of each county as a permanent point of reference.

The letters required that an identical text was published or proclaimed as it was written. Does this moment represent the traceable origin of civil-service English? This document captures the tone of the type of English spoken in London in the mid-thirteenth century. The clerk who drafted and wrote these letters was Robert of Fulham. He was an experienced Exchequer official, who also worked in the Exchequer of the Jews. His linguistic skills might therefore have stretched from Latin and French to Hebrew and English. He was rewarded with the huge sum of 50 shillings for the preparation in English and French of the letters issued by the lords of the council to be issued in support of the Provisions of Oxford.

Making the language accessible

Linguistic historians have noted the language used in this letter is conservative, even old-fashioned.[3] Where anglicised versions of French words might be expected in the text, a form of English is used that reflects a pre-Conquest older English style. Near the start of the letter, thurgh Godes fultume, meaning by God’s grace or help, is written instead of something based on the French par la grace de Dieu. The literate and illiterate subjects whom the letters were meant for – the ilærde and ileawede (literally, the learned and unlearned or lewd), are addressed in a form related to older English rather than the French clerics and lays. In these letters, the king’s natural advisors are his redesmen and not the older French language equivalent of conseillors. Many of the witnesses are titled as eorls and not French contes. These changes suggest a deliberate attempt by the administrators at the centre of government to link the language of the letters directly to the speech of the majority of the population.

Would knowing that this proclamation was written and delivered as the Crown intended have made the king’s subjects more willing to pay attention to the message it contained? One of the major consequences of the Norman Conquest of 1066 had been a conscious cultural eclipse of Anglo-Saxon Old English as the language of formal government charters and other documents. No-one would have remembered that fact in 1258. The distribution of letters in English would, however, have made a difference to the reception of specific news about the king and lords collaborating in government. The medium helped to set the tone and intention of the agreement in terms that related directly to the type of rule that people experienced on a daily basis. Although the Provisions were soon undone, with the lords themselves reverting to Latin in their documents to emphasise the legality of their position, the principle of plain English communication direct to the population had been established.

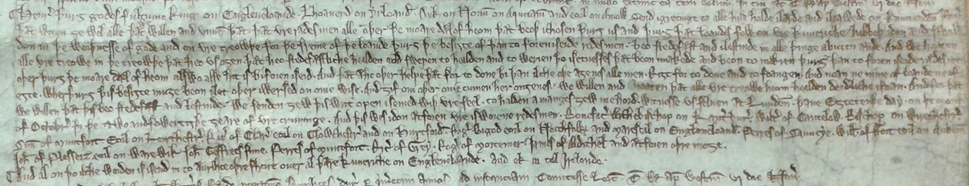

C 66/73, m/ 15 Transcription

Henri, thurgh Godes fultume King on Engleneloande, Lhoauerd on Yrloande, Duk on Norm[andi], on

Aquitaine, and Eorl on Anjow, send igretinge to aIle hise holde, ilærde and ileawede, on Huntendoneschire.

Thæt witen the wel alle thæt we willen and unnen thæt, thæt ure rædesmen alle, other the moare dæl of

heom, thæt beoth ichosen thurgh us and thurgh thæt loandes folk on ure kuneriche, habbeth idon and

shullen don in the worthnesse of Gode and on ure treowthe, for the freme of the loande thurgh the besighte of than to foreniseide redesmen, beo stedefæst and ilestinde in alle thinge a buten ænde.

And we hoaten alle ure treowe in the treowthe thæt heo vs othen, thæt heo stedefæstliche healden and swerien to healden and to werien tho isetnesses thæt beon imakede and beon to makien, thurgh than to foren iseide redesmen, other thurgh the moare dæl of heom, alswo alse hit is biforen iseid; and thæt æhc other helpe thæt for to done bi than ilche othe agenes alle men right for to done and to foangen. And noan ne nime of loande ne of eghte wherthurgh this besighte mughe beon ilet other iwersed on onie wise. And gif oni other onie cumen her ongenes, we willen and hoaten thæt aIle ure treowe heom healden deadliche ifoan. And for thæt we willen thæt this beo stedefæst and lestinde, we senden gew this writ open, iseined with ure seel, to halden amanges gew ine hord.

Witnesse vs seluen æt Lundene thane eghtetenthe day on the monthe of Octobre, in the two and fowertighthe geare of ure cruninge.

And this wæs idon ætforen ure isworene redesmen, Boneface Archebischop on Kanterburi, Walter of

Cantelow, Bischop on Wirechestre, Simon of Muntfort, Eorl on Leirchestre, Richard of Clare, Eorl on

Glowchestre and on Hurtford, Roger Bigod, Eorl on Northfolke and Marescal on Engleneloande, Perres of

Sauueye, Willelm of Fort, Eorl on Aubemarle, lohan of Plesseiz, Eorl on Warewik, lohan Geffrees sune,

Perres of Muntfort, Richard of Grey, Roger of Mortemer, Iames of Aldithele, and ætforen othre inoghe.

And al on tho ilche worden is isend into æurihce othre shcire ouer al thære kuneriche on Engleneloande,

and ek in-tel Irelonde.[4]

Translation

Henry by God’s grace, king of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Normandy and of Aquitaine and Earl of Anjou, sends greeting to all his subjects, learned and lewd, in Huntingdonshire. You all know well that we want and desire that our counsellors the greater part of whom have been chosen by us and by the people in our kingdom, have acted and should act according to the honour of God and loyalty to us, and for the good of the realm, according to the provisions of those aforesaid counsellors, that they be steadfast and firm in all things forever.

And we command and admonish all faithful and loyal men by the fealty that they owe us, firmly to hold and to swear to observe and maintain those statutes which have been made or shall in future be made by the council or by the majority thereof in the manner stated. And that all men aid each other in doing this by the same oath against all men who either give or receive a bribe. And that none shall take land or goods to any way which would infringe or impair this provision in any way. And if any should oppose this decree, we will and command our faithful subjects to treat them as our mortal enemies. And since we wish this act to be firm and enduring we are sending our letters patent sealed with our seal, to every county to remain there in its archives.

Witness ourselves at London the 18th day of October in the 42nd year of our reign.

And this act was done in the presence of our counsellors Boniface, archbishop of Canterbury, Walter di Cantelup, bishop of Worcester, Simon de Montfort, earl of Leicester, Richard de Clare, earl of Gloucester and Hertford, Roger Bigod, earl of Norfolk and marshal of England, Humphrey de Bohun, earl of Hereford, Peter of Savoy, William de Forz, earl of Albermarle, John de Plessis, earl of Warwick, Roger de Quincy, earl of Winchester, John FitzGeoffrey, Peter de Montfort, Richard de Grey, Roger de Mortimer, James de Audley, Hugh Despenser and others after them

And similar letters are to be sent to every other shire within the kingdom of England and likewise into Ireland.

[1] M. Richardson, ‘Henry V, the English Chancery and Chancery English’, Speculum, 55, no. 4, October 1980, 726-50

[2] The significance of this document has been thoroughly analysed in M.T. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England 1066-1307 (2nd edn, Oxford, Blackwell, 1993), pp. 220-2. This blog post offers no new insights, but does put themes in a broader context.

[3] David Burnley, The History of the English Language: a sourcebook, pp. 116-17; Hans Friede Nielsen, From Dialect to Standard English, 1154-1776, vol. II, pp. 123-7; Seth Lerer, Inventing English: A Portable History of the Language p.p. 54-8.

[4] This is the Middle English version of the French text found in Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1247-58, p. 655-6 (C 66/72, m. 1). This also exists in a different translation in R.F. Treharne and Sandars, Documents of the Baronial Movement of Reform and Rebellion, 1258-1267 (Oxford, OUP, 1973), pp. 118-22.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.