On 5 December 1916 Herbert Henry Asquith, the Liberal Prime Minister who had governed Britain for more than eight years, resigned. Asquith did not relinquish office willingly. He had successfully reconstituted his government as a wartime Coalition with Conservative and Labour support just eighteen months earlier, and his fall from power took many observers by surprise. No general election had been held, no vote of confidence had been lost in the House of Commons, nor had any formal challenge been made to his position as leader of the Liberal Party. His ejection from office was effectively a political coup d’état, the result of an intrigue between the War Secretary David Lloyd George – a fellow Liberal, who had served before the war as Asquith’s Chancellor of the Exchequer – and senior members of the Conservative Party. Having lost faith in Asquith’s ability to secure victory in the Great War, Lloyd George, supported by the Conservative leader Andrew Bonar Law, threatened to resign from the government unless the Prime Minister agreed to turn over responsibility for the day-to-day running of the conflict to a small executive ‘War Cabinet’. Rather than acquiesce to this humiliation Asquith dissolved his government, and two days later Lloyd George formed a new Coalition ministry with the backing of the Tories.

Scourge of the establishment

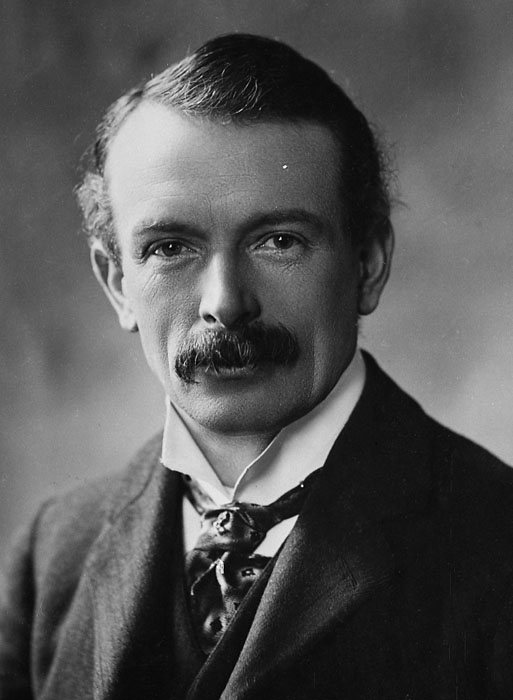

The installation of Lloyd George in 10 Downing Street with Conservative support would have seemed almost unthinkable, even a few years earlier. During the decade before the outbreak of the war he had cultivated a reputation as the scourge of Britain’s Tory, aristocratic, and Anglican establishment. As Chancellor of the Exchequer, and architect of the famous ‘People’s Budget’ of 1909, he had enraged Tory opinion by promising to levy new taxes on land and engaging in inflammatory rhetoric against his political opponents in the House of Lords – a body he described as comprising ‘five hundred ordinary men chosen at random from amongst the unemployed’.

Lloyd George’s emergence as a prospective ‘war leader’ was no less remarkable. He had first achieved national prominence at the turn of the century as a critic of the British war in South Africa – a stance which had earned him the enmity of Tory imperialists. According to one legend, he had been forced to flee from Birmingham town hall in 1901 disguised in a police uniform, when an anti-war meeting was attacked by a ‘jingo’ mob. Even in 1914, as the diplomatic storm clouds gathered over Europe, Lloyd George had initially appeared ambivalent over the prospect of British involvement in a continental war. He was not, however, a pacifist, and once the die was cast he threw himself behind the war effort. In a powerful speech at the Queen’s Hall in London on 19 September 1914, he declared that ‘it will be a terrible war; but in the end we shall march through terror to triumph’.

‘man of push and go’

Recognising that this would be a new type of ‘total war’, Lloyd George soon became frustrated with the government’s ‘business as usual’ approach. In 1915 he took charge of the newly-created Ministry of Munitions, where he overhauled the production of high explosive shells. More controversially, he also began calling for the introduction of military conscription in order to sustain the large army that would be needed to inflict a ‘knock-out blow’ on the Central Powers. Compulsory service was supported by many Conservatives but opposed by most of the Liberal leadership. By the time it was finally introduced in 1916 a political gulf had opened up between Lloyd George and most of his senior Liberal colleagues, including the Prime Minister, whose equivocations and delays over conscription had infuriated the government’s Conservative critics. Tories now hailed Lloyd George as a ‘man of push and go’, a patriot with the vision to deliver military victory, while Asquith was derided for his ‘wait and see’ approach and his failure to exert a firm grip on the direction of the war.

Fight for the soul of the Liberal Party

Yet the struggle for power between Asquith and Lloyd George was not simply a contest between two different styles of wartime leadership. It quickly came to be seen as a fight for the very soul of the Liberal Party. Admirers of Lloyd George denounced the Asquithian Liberal leadership as being ideologically inflexible and lacking in vision, clinging to laissez-faire Gladstonian principles that were at best outdated and at worst dangerous in the context of a national struggle for survival. On the other side, supporters of Asquith claimed that Lloyd George had betrayed not only his leader but his party and his political principles. In his enthusiasm for military conscription he had cast aside traditional Liberal concerns for individual conscience and the liberties of the citizen; he was to be Britain’s last Liberal Prime Minister, but in a government propped up by Tories. The reputation he gained during the war – of a cynical politician who abandoned his Liberalism in pursuit of power – followed him to the end of his life. In the damning verdict of the economist John Maynard Keynes, Lloyd George was merely a political adventurer, ‘rooted in nothing’.

In fact, both narratives distorted the truth. Asquith was never as ineffective a war leader as many of his critics claimed. During his premiership, Britain raised the second-largest volunteer army in history (the largest was the Indian Army during the Second World War), the military high command was reorganised, and the machinery of state was adapted to meet the challenges of industrialised warfare. By the end of 1916, many of the building blocks that would make possible the final victory of 1918 were already in place.

Ideological compromises of Asquith’s regime

In this context, those who condemned Lloyd George for abandoning his Liberalism often tended to forget just how many ideological compromises had already been made by the Asquithian regime. It was Asquith who had dissolved the last Liberal government in May 1915 and brought the Conservatives into his Cabinet, while many of the most notorious ‘illiberal’ wartime measures – the Defence of the Realm Act and, of course, military conscription – were introduced on Asquith’s watch. Indeed, the Prime Minister’s cautious approach to the conscription controversy had been driven less by fidelity to Liberal principles than by the pragmatic calculation that such a radical innovation could only be introduced with something approaching ‘general consent’ from the public, and in particular the trade unions, whose cooperation remained vital to the war effort. Military compulsion could not be rushed, but could only be introduced once the volunteer system were seen to have ‘failed’.

Ultimately, the collapse of Asquith’s premiership arguably owed less to his personal shortcomings as a war leader or his inflexibility as a politician than to the inherent weakness of a particular model of coalition government. Asquith had invited the Conservatives to join his administration in 1915 largely as a means of avoiding a risky wartime general election. But he never had any serious interest in sharing power with them, and went to considerable lengths to keep key ministerial posts in Liberal hands. The Conservatives would share responsibility for the management of the war effort, but would have only limited power to shape it. Asquith’s coalition never became a ‘National Government’ in any meaningful sense. It was never marked by any significant unity of purpose. Partisan rancour between Liberals and Tories continued to simmer beneath the surface, and few Conservatives developed any sense of loyalty to the Prime Minister.

Overhaul of Liberal principles

Once elevated to the premiership, Lloyd George was far more generous to his Tory partners – Conservatives were offered control of the Exchequer, Foreign Office, Home Office, Admiralty, and War Office. But it would be wrong to describe him as being in thrall to the Conservatives. He might have been more flexible in his political thinking than many other leading Liberals of his day, but he always denied that he had abandoned his Liberalism. Rather, he argued that Liberal principles needed to be reconsidered and applied in new ways in the peculiar context of war. Even conscription, Lloyd George argued, could be defended as the most ‘democratic’ and egalitarian means of raising a national army – one which enshrined the principles of ‘equality of sacrifice’ and common citizenship, and had been embraced throughout history as a tool in defence of democracy, from the Levée en masse of the French Revolution to Abraham Lincoln’s efforts to save the Union during the American Civil war.

A Radical still

Despite the enmity of many of his former Cabinet colleagues, Lloyd George retained the support of a sizeable element of the Liberal Party in Parliament – in particular the backbenchers in the pro-conscription Liberal War Committee – and of Liberal intellectuals and journalists such as the historian H. A. L. Fisher and C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian. Above all, in his dynamic and resourceful approach to politics, Lloyd George remained a Radical. The manner in which the Conservatives turned on him and ejected him from office in order to return to single-party government in 1922 demonstrated how few of them had ever truly accepted him as one of their own.

The pre-war partnership between Asquith and Lloyd George as Prime Minister and Chancellor had been one of the most effective in modern British political history. The rift between them in 1916 was hugely damaging to the fortunes of the Liberal Party. It forced Liberals to choose between two rival leaders – a split in the party that was formalised in the 1918 ‘Coupon’ Election, and only healed in 1923. By this time a surging Labour Party, whose electoral horizons had expanded markedly during the war, had overtaken the Liberals as the principal opposition to the Conservatives. The politics of the 1920s was to be shaped around a contest between Labour socialism and Tory anti-socialism, and the Liberals slipped into irrelevance. They never again held power as an independent party of government.

Further Reading:

G. H. Cassar, Asquith as war leader (1994)

J. Grigg, Lloyd George: war leader, 1916-1918 (2002)

J. Turner, British politics and the Great War: coalition and conflict, 1915-1918 (1992)

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.

2 comments

Comment by James Temple posted on

As an American, many of the nuances of British politics and government are a bit vague to me, but I very much enjoy these blog entries as a way to enlighten myself. I find them well written and informative without being stuffy or too academic.

Keep up the good work!

Comment by Mark Dunton posted on

Thank you James, for the great feedback