On 31 August 1907, Britain and Russia signed an agreement in St Petersburg which put in place the final piece of the alliance system which has widely been considered to have been a major contributing factor regarding the outbreak of the First World War.

Since 1918 the Entente has been attributed to concerns about the rise of Germany. Yet the agreements did not mention Europe, but focussed on Persia, Tibet and Afghanistan. There were good reasons why Britain and Russia focused on this area, including resolving the historic tension over the region that dated back to the 1830s which had been described as ‘the Great Game’.

In the usual manner of colonial agreements, the negotiations were conducted without consulting the countries concerned, and effectively made them protectorates. Although frequently regarded as one subject, the Entente consisted of three separate agreements about Persia, Afghanistan and Tibet, combined into one for ratification purposes.

The agreement

In 1901 Russia opened two consulates in Persia, investing in the Persian railways. The two countries shared a border of more than two thousand kilometres. Persia was an important export market for Russian manufacturing. The agreement divided Persia into three zones, a large Russian zone to the north, and two smaller zones, one which neither country dominated, and a British zone to the south.

Afghanistan was less of a trade partner to Russia, but there were concerns about the border, in relation to crime, refugees and diseases. This was the area over which there had been the longest disagreement between Britain and Russia. For Britain, Afghanistan signified access to India.

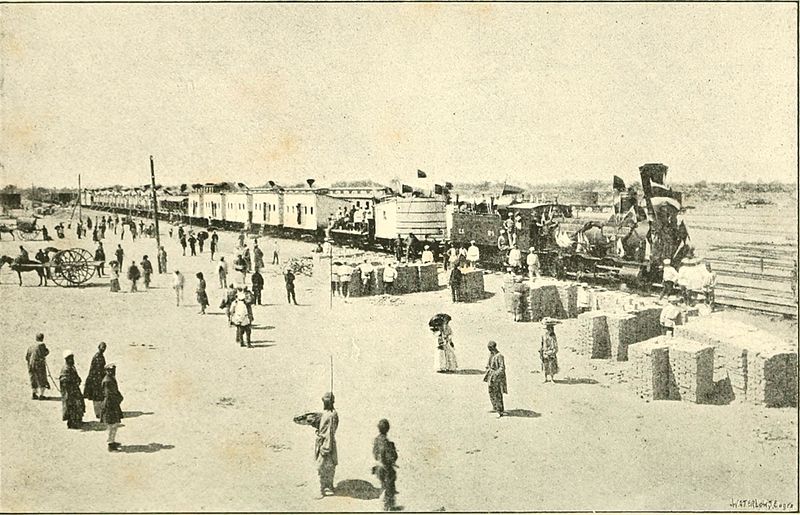

The Russians were conscious of British sensitivities with regards to any country bordering India. Russia had built railway lines up to the border with Afghanistan. The British Government feared India would be attacked but calculated that increasing the number of troops stationed there to the levels necessary to resist any attack was prohibitively expensive. Britain had already faced the cost of the Second Boer War: diplomacy was cheaper. The agreement over Afghanistan was a concession by Russia, recognising Afghanistan as “outside the sphere of Russian influence”.

With regards to Tibet, Russia’s proclaimed interest was in enabling their Buddhists to consult with the Dalai Lama on religious matters. Its significance was the potential interest of the other country. Both countries affirmed that business with Tibet would be conducted through the Chinese Government.

The wider bilateral relationship

By the beginning of the twentieth century Britain was moving out of the so-called ‘splendid isolation’ it had adopted in the late nineteenth century. In 1902 it entered an agreement with Japan and in 1904 established the Entente Cordiale with France. From the British perspective, the Anglo-Japanese Alliance was created partly with the aim of preventing Russian expansion or, even worse, a separate Russo-Japanese understanding which would undermine the British position in the Far East. This alliance with Japan was renewed in 1905 in the midst of its war with Russia; its focus was on broader stability in the Far East.

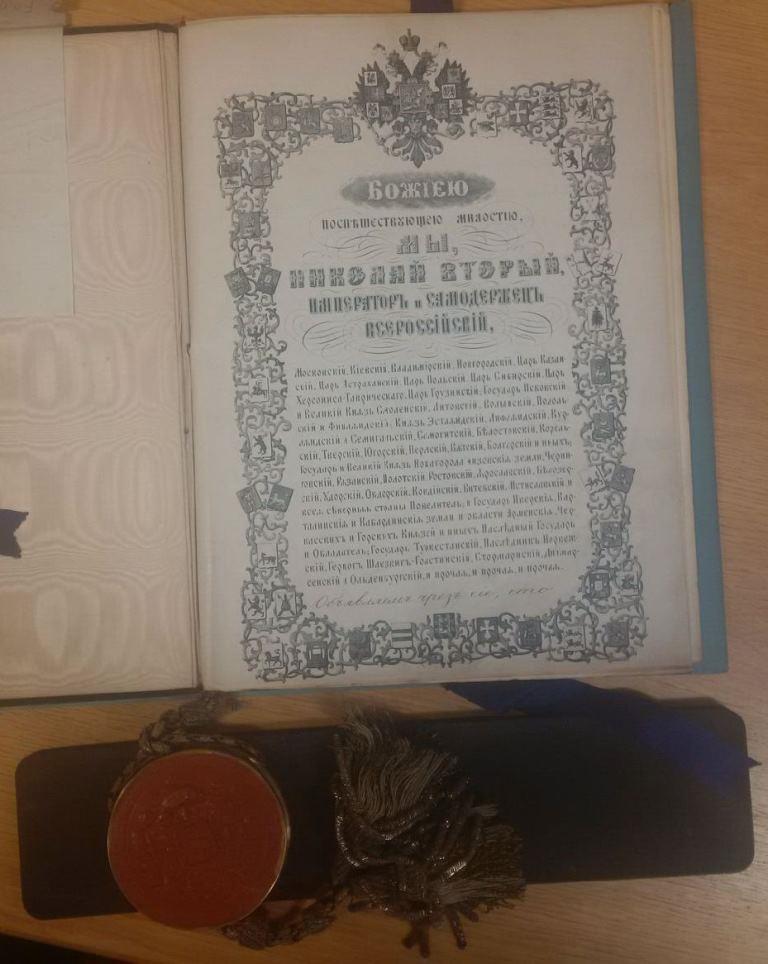

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 was the turning point in Russia’s bilateral relations with Britain. Russia had decisively lost the war, whilst at the same time experiencing revolutionary turmoil. The resulting Russian Constitution of 1906, its first, removed the absolute power of the monarchy and established a parliament, taking inspiration from several established constitutions, including that of Japan. Russia was beginning to look outwards again.

Despite Britain’s alliance with Japan, neither Britain nor Russia wanted to fight one another. This was demonstrated in the Dogger Bank incident of October 1904, when boats from the Baltic Fleet wrongly identified British fishing vessels as Japanese warships and fired upon them. Both sides agreed to refer the matter to international arbitration and further escalation was avoided. Aside from this incident, the likelihood of Britain and Russia declaring war against one another was low. The greater risk lay in the possibility of a proxy war or a crisis in another country escalating, with the entrance of other countries creating a large scale war.

Similar tensions to those about Persia and Afghanistan were addressed with the Anglo-French Entente. Under this agreement, neither Britain nor France would obstruct the other in Morocco or Egypt, and would maintain the status quo there.

Diplomatic actors

There were a number of key individuals who were instrumental in furthering the understanding between Britain and Russia. The Russian Ambassador to the UK, Sergei Dmitrievich Sazonov, was on his second tour of duty in the UK from 1904-07. The Russian Foreign Secretary, Alexander Petrovich Izvolsy, worked with his allies in government to promote the agreement. He supported the entente, despite domestic opposition, and in 1907 succeeded in introducing an agreement with Japan. Cecil Spring-Rice was the British Ambassador to Moscow from 1903-06, then to Tehran from 1906-08. Inversely, Arthur Nicholson, who had previously served in Tehran, became British Ambassador to Moscow in 1906. The turning point in British commitment came with the election of the Liberal Government in 1906 and the appointment of Sir Edward Grey as Foreign Secretary.

International agreements did not mean that the agreeing nations were automatically allies, although these understandings made wider cooperation more likely, nor were they always reflections of mutual trust and values. Treaties were a diplomatic means of reducing the risk of war, by identifying potential flashpoints and agreeing the division of interests. Ultimately the entente reduced tension between Britain and Russia at a critical point.

Many countries in Asia were covered by such agreements, with the colonial powers marking their interests through them, but this type of approach was not just limited to far away countries. There was even an agreement in 1907 between Russia and Austria about maintaining the status quo in the Balkans, one that would be long abandoned by the summer of 1914.

Suggestions for further reading

Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe went to war in 1914 (London: Allen Lane, 2012)

Dominic Lieven, Towards the flame: Empire, war and the end of Tsarist Russia (London: Allen Lane, 2015)

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.