Sunday 15 October marks the centenary of the execution of Madame MacLeod, neé Margaretha Zelle, best known as Mata Hari. A Dutch dancer, in the early twentieth century she was considered one of the most dangerous female spies of the First World War. Although she was a Dutch citizen who never lived in Britain, her story was more international and British, than originally apparent.

Early years

Born in the Netherlands in 1876, her father’s business failed when she was 13, and her mother died less than two years later. At 18 she made an improvident marriage to Captain Rudolph MacLeod, a Dutch Army officer of Scottish descent. When the marriage broke up in 1902 she moved to Paris and started a career as an exotic oriental dancer.

By 1914 her career was no longer flourishing, but she supported herself through occasional work and the contributions of wealthy sponsors. She was a courtesan. At the start of the First World War she was in Berlin. Because of her residency in Paris, the German Government regarded her as a French citizen. They froze her bank account. As her agent and the costumier were concerned they would not be paid, they retained her furs and her jewellery. She was only able to return to Holland with the assistance of a Dutch compatriot.

British suspicions

Travelling into or out of a country in the war zone was not straight forward. It required the correct permits, and meant transiting through Switzerland, Britain or war-torn Belgium. In December 1915, when returning to France from Holland, Mata Hari was detained and questioned by British police. They searched her belongings, but found nothing incriminating. After her departure, MO5, the forerunner of MI5, issued a note to port authorities stating that she should not be allowed to return to Britain. A few months later they issued a further circular, stating that if she returned she should be arrested.

Why was the British Government suspicious of her? Britain was in a state of spy fever during the First World War. Mata Hari’s lifestyle would have raised particular suspicion. She was a divorced woman, who obviously liked luxury (she had ten trunks of luggage with her when she was arrested), her act was considered highly sexual. She was a talented linguist. She liked soldiers, irrespective of their nationality. Although she was a citizen of a neutral country she was travelling into and out of France, and was in Berlin at the start of the war. The most damaging fact against her was that she provided conflicting reasons for travelling to France. On her return to Holland MO5 kept her under observation through their correspondent in the Hague.

French actions

The British informed the French of their concerns. Captain Georges Ladoux, the Head of the French Intelligence Bureau, decided to test her and asked her to spy for France. She agreed but demanded a million francs in return, enough for her to stop working and marry her Russian lover, Captain Vladimir de Masloff. She targeted the German Military Attaché in Madrid, Major Arnold Kalle, but her clumsy attempts at ascertaining information alerted him to her intentions. Using a German code which he knew had been broken by the British, he transmitted the message ‘The British are now running France’. Unsurprisingly, the French intercepted it.

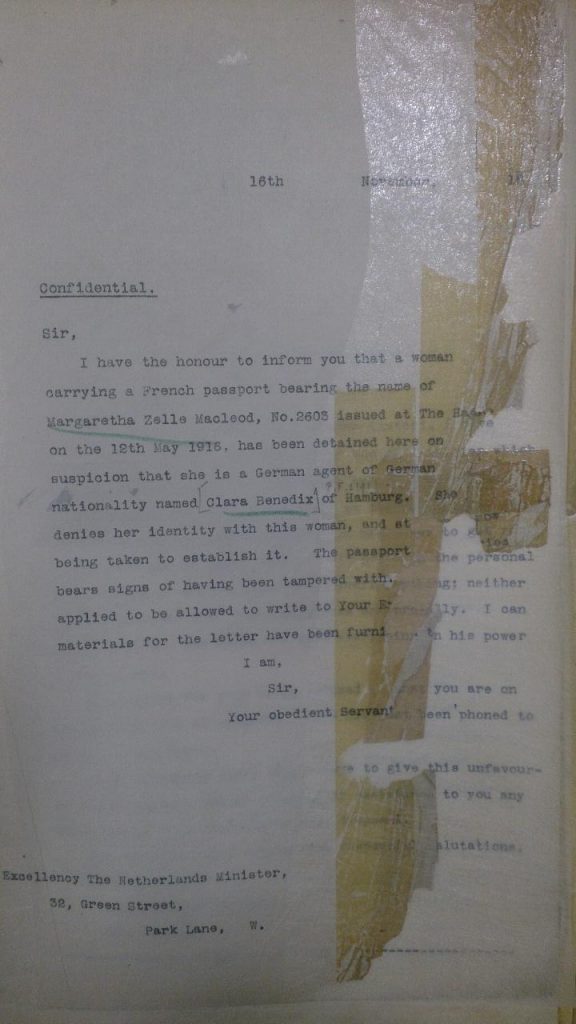

In spring 1916, attempting to return to Holland via Spain, Mata Hari was forced to transit through Britain. Following a case of mistaken identity, where she was assumed to be Clara Benedix, a German spy, she was detained and questioned for a number of days. The file notes indicated that her passport showed signs of tampering. The British authorities realised that if she were a spy, she was an ineffective amateur rather than a master-criminal. On their reporting the interview to the French, Ladoux denied that she was spying for France and requested that she should be returned to Spain. The British authorities obliged. All the time she was desperate to travel to Vittel in France, where Captain Masloff was recuperating, but travelling there required a permit. She applied for one but was refused. When she asked the Dutch authorities to enquire about why she was not permitted to travel to France, they informed her that it was because she was ‘on the English list of suspects’.

On her second war-time trip to France in June 1916, the Police Intelligence Bureau began to follow her.

The French arrested her in February 1917 on a charge of espionage and put her on trial in July the same year. Amongst the many accusations made against her, the prosecution claimed that she had discovered and betrayed vital information about the British tanks, prior to their first deployment at the Somme in 1916. Yet when she was executed in October 1917 the French Government did not inform Britain about her execution, as it was not felt to concern them. The British Government discovered the news in the press.

The press variously described her as Dutch, Indonesian, Indian, and even Japanese, reflecting the exotic persona she adopted as Mata Hari. The number of languages they claimed she spoke was even broader, including all those of her alleged nationalities as well as German, French, English and Portuguese.

MI5’s files on Mata Hari were made public by The National Archives as part of a wider release of intelligence papers related to the centenary of the First World War. Rather than portray her as the exotic, dangerous intriguer of repute, they show the intelligence services dismissed her as a threat.

Further reading

Julie Wheelwright, The fatal lover: Mata Hari and the myth of women in espionage (London: Collins & Brown, 1992)

National Archives Files KV 2/1, KV 2/2, MEPO 3/2444

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.