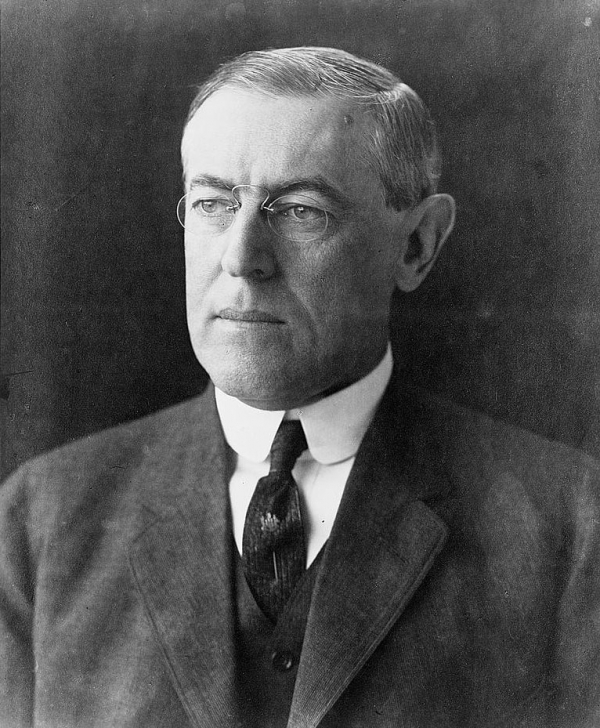

One hundred years ago today US President, Woodrow Wilson, gave his famous speech to Congress articulating the Fourteen Points and principles that he believed should be the foundation of post-war peace.

The speech

When he declared war on Germany in April 1917 Wilson did so stating that the United States was an ‘associated power’ rather than an ally with France and Britain, distancing it from allied war aims.

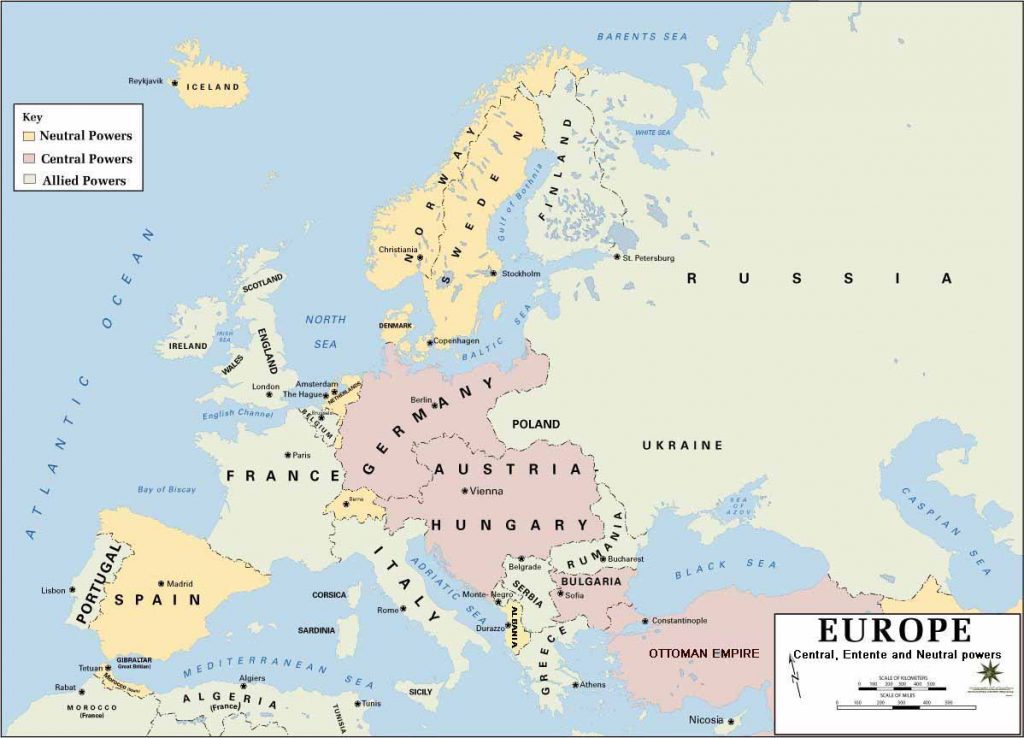

The Fourteen Points set out Wilson’s programme for world peace. These addressed the actions he considered to have been responsible for the war, namely secret covenants, economic barriers to trade, lack of freedom of navigation of the seas, and national levels of armaments. Eight points elaborated on territorial matters related to specific countries, including the restoration of Belgium, Alsace-Lorraine being returned to France, the creation of an independent Poland, an adjustment of the Italian frontiers, and granting Serbia access to the sea. There were additional points proposing the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires (despite the fact that the US did not declare war on the Ottoman Empire). The longest point related to Russia, which at that time was in separate peace negotiations with Germany at Brest-Litovsk. The treatment of Russia, President Wilson argued, would be the acid test of the belligerents’ good will. Some commentators regarded this as an attempt to keep Russia in the war.

The last, and most famous point, was the suggestion for the formation of an international association of nations ‘for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small nations alike’. Interestingly, although the speech is associated with national ‘self-determination’, that phrase was not used on this occasion, although there were criticisms of imperialism – but with specific mention of the Empires of the Central Powers only.

Reception

The speech was reported around the world, international reactions varied. The British Press were positive. But while the British and French Governments seemed to welcome the speech, they were non-committal about the points raised, and did not modify their war aims in response. Wilson had not consulted them before making the speech. The British Government differed on the principle of freedom of navigation of the seas (which the Royal Navy would not accept). The Prime Minister, Lloyd George, felt that Russia could ‘only be saved by her own people’. The French Government thought that Wilson was naïve in trying to negotiate with Germany, and that the goals were overly ambitious. As President Clemenceau wryly pointed out, Wilson had Fourteen Points, God only had ten.

The response from the German Government, made by Chancellor Count von Hertling, was largely conciliatory. He accepted the principles about open discussions and economic barriers. Other points were open to discussion, such as arms limitations, and an international gathering of nations. He considered that President Wilson’s principles in relation to freedom of the seas should be applied to the allies as well. But the frontiers of specific countries were a matter for peace negotiations or those countries concerned only. On this basis, the question of Russia was being dealt with by Russia and the Central Powers.

‘Peace without victory’

At the time of the speech, the war appeared to be turning in favour of the Central Powers. As Russia was no longer fighting, Germany would shortly be in a position to transfer large numbers of troops from the Eastern Front to France and Belgium. Although US troops had started arriving in France in June 1917, they were neither deployed nor ready to fight. In January 1917, Wilson had famously advocated a ‘peace without victory’ but by the time of his speech a year later, the US had not suffered the large scale losses of men as the other belligerents had. The acceptance of such heavy casualties since 1914 without a victory would prove impossible to both sides as it would signify to their peoples that the war had been for no purpose.

On 11 February 1918 President Wilson made a further speech to Congress, expanding upon the Fourteen Points. In it he stated that the fate of nations and peoples should not be a matter of bartering and well-defined national aspirations should be granted as much as possible. From this speech onwards, the different parties diverged more.

President Wilson’s blueprint was significant but not because it brought an early end to the war. In November 1918, when the Germans indicated their willingness to consider signing the armistice it was with the understanding that the Fourteen Points would be used as the basis for the negotiations. The problem was that Wilson’s vision did not take into account the claims of France and Britain and their allies.

Its most noted legacy was in the establishment of the League of Nations (although unlike Wilson’s ideal this was separate from the peace treaties and initially Germany was not admitted). Ironically, the US never joined due to opposition in Congress and American unwillingness to involve itself in European affairs.

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.