On Sunday, 20 February 1938, after two days of fraught Cabinet discussion, Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden told Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain that he must resign rather than agree to enter into early talks with the Italian government led by Mussolini. Eden’s resignation has often been portrayed as a principled rejection of appeasement, but in fact, as the Cabinet discussions showed, he and Chamberlain differed not on principle but on method and timing. Eden felt Mussolini must offer some sign of good faith first, such as stopping Italian submarines attacking British ships off the coast of Spain. Chamberlain, though he described Italy as a ‘hysterical woman’, felt it important to show Mussolini ‘that he might have other friends beside Herr Hitler’.

Neither Chamberlain nor Eden saw appeasement as a dirty word: it meant the pacification of Europe, a state profoundly to be desired. Both men accepted the need to improve relations with Italy, to weaken the Rome-Berlin axis and avoid fighting two major European enemies at once (with an aggressive Japan waiting in the wings); both rejected Hitler’s ambitions for a free hand in Eastern Europe and Russia and for territorial changes brought about by force; both accepted that conflict with Hitler’s Nazi Germany was probably inevitable, but that delaying that confrontation was essential to give time for Britain’s rearmament. So why did Eden resign? The reasons lie in the personal and psychological, as well as political context.

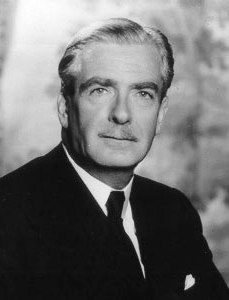

Eden and Chamberlain: men with a mission

Eden and Chamberlain had poor personal chemistry and had become exasperated with each other. Each thought himself better qualified to work for peace and to delay, if not avoid war. Eden had longer professional experience in international affairs, but Chamberlain had been dabbling–many said interfering–in foreign affairs long before he became Prime Minister in May 1937, and understood the costs of rearmament. A tough-minded man with a strong belief in his own convictions, Chamberlain was impatient with the professional caution of the Foreign Office. He relied on his own advisers, principally senior civil servant Sir Horace Wilson, and Sir Joseph Ball, former MI5 officer now Director of Research at Conservative Central Office, for information and back-channel diplomacy.

Eden was also confident in his own judgement, encouraged in this by his FO officials, who followed the line that Britain should reject territorial change by force but neither say it would, nor that it would not fight in any given circumstance. The support of men like Oliver Harvey, who told Eden he was the most important person in the Cabinet and that the government would fall if he resigned, increased the Foreign Secretary’s willingness to dispute Chamberlain’s authority. Sir Alexander Cadogan, FO Permanent Under-Secretary, thought Eden ‘exaggerates as much one way as PM does on the other’.

Facing the Dictators: the European context

The British government had been actively seeking better relations with both Nazi Germany and Italy since the summer of 1937, Chamberlain taking the opportunity of Eden’s holidays to see if anything might be done to deflect Hitler and Mussolini from aggression, Eden working through the League of Nations and other international groupings. The Chiefs of Staff insisted that Britain would not be ready for war before 1939, and refused to enter into any meaningful staff talks with the French, whom they did not trust. In Cabinet on 16 February 1938 the Minister for the Coordination of Defence pressed for action to reduce the number of potential enemies since Britain was not equipped to defend the Empire against three major powers. British forces were already stretched: for example, 20,000 troops were committed against the Arab rebellion in Palestine which had erupted again in November 1937. Britain’s overseas intelligence organisation, the Secret Intelligence Service, was overstretched and underfunded, and unable to supply reliable information on German or Italian military preparations. Military and intelligence chiefs alike agreed that Britain was not ready to go to war.

Hitler and Mussolini also hoped to avoid war with Britain while achieving their own ambitions. Mussolini was agitating for recognition of his conquest of Ethiopia, and sought dominance in the Mediterranean; Hitler, ostensibly angling for colonial concessions in Africa, was firming up his plans for action against Austria and Czechoslovakia. At the beginning of February 1938 Hitler engineered a major purge of the military, assuming personal command of the armed forces (leading the Chief of SIS to try and recruit disaffected German officers). In the Soviet Union, although purges were decimating the military hierarchy, Stalin played all ends against the middle, developing his links with Germany while promoting Russian influence in Western Europe. The backdrop was the Spanish Civil War, a proxy conflict with the Soviet Union, Germany and Italy all trying out their latest armaments against, or in support of General Franco. International efforts to negotiate a peaceful solution or impose non-intervention had failed.

The Far Eastern Context

The outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in July 1937 threatened British interests, particularly in China. Japanese policy was to dominate mainland China before risking armed conflict with other major powers, but Tokyo had strong links to Berlin and Rome. Chamberlain sought back-channel negotiations with Japan to try and avert the danger of a Triple Alliance against Britain; Eden put his faith more in the Americans, though Roosevelt, while making speeches about lawless behaviour, was unwilling to commit the US to action. Chamberlain considered it ‘best and safest to count on nothing from the Americans but words’, but though Eden shared his frustration with American isolationism, he was horrified when in January 1938 Chamberlain gave a dismissive reply to a rather vague Roosevelt initiative for a peace plan. FO policy was to keep the Americans close at all costs, and the profound disagreement between Eden and Chamberlain on this point contributed to the crisis culminating in Eden’s resignation.

In the end, it was personal incompatibility rather than policy that was decisive in Eden’s resignation. As Cadogan put it: ‘an ordinary man ought to have stayed. A., being what he is, was right to go.’ Over the past 80 years, that resignation has enhanced Eden’s reputation, while Chamberlain’s has declined. In the context of British policy, this is unfair.

Suggestions for further reading

Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1939, Second Series, Volumes XIX and XXI

George C. Peden, ‘Sir Horace Wilson and Appeasement’, Historical Journal, 2010, 53(4)

Gill Bennett, ‘The Roosevelt peace plan of 1938’, FCO Historians Occasional Papers, No. 1, 1987

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.