The Berlin Blockade began 70 years ago, in June 1948, and became one of the first great tests of the Cold War. The Allied response, in the form of the Berlin Airlift, contributed to the formation of NATO and the creation of the Federal Republic of Germany. It also prevented the starvation of the two and a half million inhabitants of Berlin. But the Airlift was entirely improvised, and for a long time no one could be sure that it would succeed.

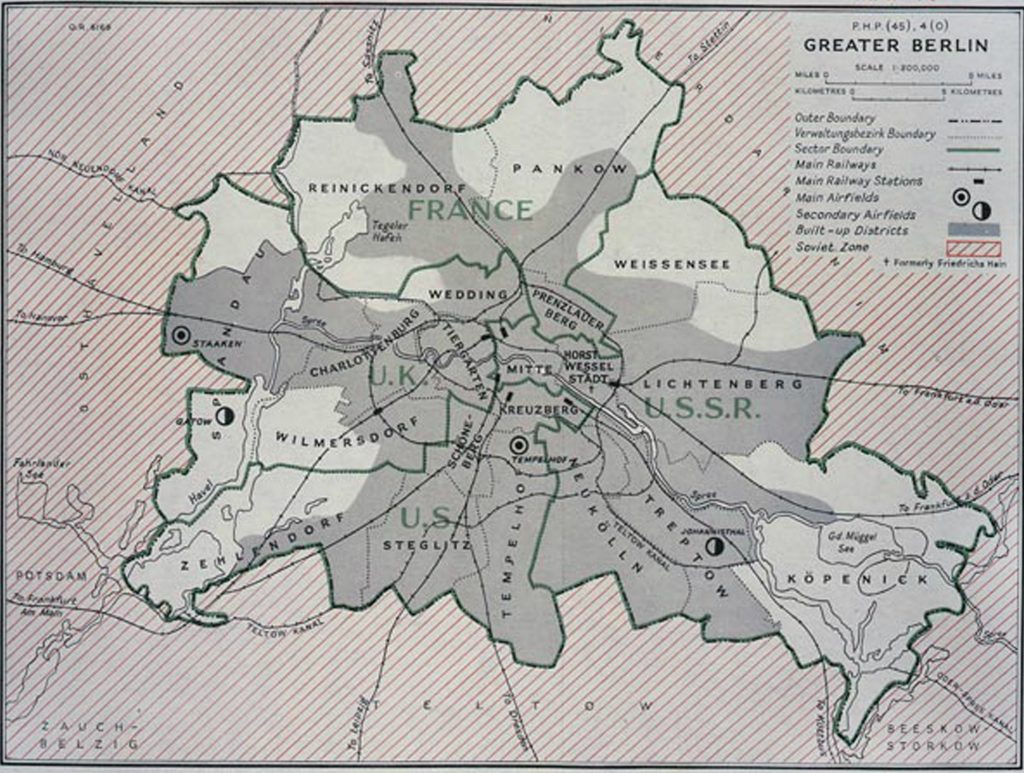

Immediately after the Second World War, Europe was divided in two, in Churchill’s words, by an iron curtain, with communism versus capitalism, and East versus West. Nowhere was this division more apparent than in Berlin, a city divided into four allied occupation zones, those of the USSR, US, France and Britain. An Allied Control Council, made up of all four powers, took joint decisions on the running of the city.

Economically, Germany was a mess. By 1948 industrial output was down to half of its pre-war rate. Looting and other crimes were rife. Approximately a third of the economy in the US-British sectors in Berlin was based on barter as people sold their belongings to survive. Rations in some parts of Germany fell to as little as 900 calories per day.

In February 1948 the Americans and the British proposed that the four occupying powers should introduce a new currency for all of Germany. This did not suit the Soviets, who had been stripping assets from East Germany as war reparations. In March, the Soviets argued that the bipartite agreements between the US and Britain contravened the principle of collective decision making and withdrew from the Allied Control Council. A unified approach to the city was no longer possible.

Berlin was a hundred miles into Soviet-controlled territory in East Germany. The presence of a capitalist area isolated like an island a hundred miles inside communist territory irritated the Soviets, who wanted the western powers to leave Berlin. They also did not want Germany to be rebuilt.

The final straw for the USSR came on Friday 18 June when the Americans, British and French collectively launched the Deutschemark. Although the new currency was not a surprise, the timing had been kept secret until after the banks had closed that day. The Soviets anticipated that the introduction of the new currency would make the Reichsmark worthless, declared its replacement illegal and immediately began to close access to West Berlin. Street blockades were erected and Allied trains turned back, so that they could not enter the occupation zones. Over the next ten days the Soviets also extended the blockade to all rail and water routes. This cut the two million people in West Berlin off from outside support. The only option for the allies to support the population was by air, since air corridors into Berlin had been agreed by the victorious powers at the Potsdam Conference in 1945, and the Soviets never seriously challenged this agreement. At first both the British and Americans doubted whether such an ambitious operation would be possible. But the alternative was to abandon the city to the Soviets, a principle contrary to the Truman doctrine of opposing the expansion of Soviet territory. Czechoslovakia had fallen to the Soviets in February 1948. If Berlin also fell, the Allies believed, Stalin’s expansion would not stop there.

The first American and British planes arrived on 28 June at the US airhead at Tempelhof and RAF Gatow. Initial estimates were that the airlift needed to transport 4,500 tonnes of goods into West Berlin every day, although it took a while to reach that amount. By the autumn this was raised to 5,000 tonnes. Of this, food accounted for around 2,000 tonnes with coal the majority of the rest. The Soviets also restricted the electricity supply to West Berlin to between 11pm and 1am. In November, the French finished building Tegel airport in their sector, completed in 90 days to ease the pressure on Tempelhof and Gatow, while the British also flew Sunderland flying boats from Hamburg, landing on the River Spree and the lakes surrounding Berlin.

The conveyance of goods was always challenging. There were only three air corridors, each 20 miles wide, into West Berlin, so the arrival of planes needed to be carefully timed. By winter, freezing conditions made flying difficult. With only a few airports, turn-around time needed to be swift. This was the first time a city had been kept alive solely by air supply and no-one knew how long the blockade would last. The Soviets gave the West Berliners the option of transferring to East Berlin and registering for a ration card. In total, only 20,000 people did; life in the communist zone was not a popular aspiration.

The airlift provided more than essentials however. A US pilot, Gail Halvorsen, noticed a group of children gathering near the airport. Whilst children usually asked servicemen for candy, these children made no request. Halvorsen offered them the two sticks of gum he had with him, which they shared between them. Touched by what he saw, he promised to bring more candy the next day. He kept his word and persuaded other pilots to give the children their sweet rations. To this day he is known in Berlin as the ‘Candy Bomber’.

The blockade lasted until 12 May 1949 when the Soviets realised that their strategy had failed and reopened the land routes into West Berlin. The airlift continued until 30 September to ensure sufficient supplies in Berlin in case the barricade was re-imposed. Over the course of the blockade, 277,804 allied flights carried 2.3 million tonnes of supplies. At its busiest, one flight landed in Berlin every minute. By fine-tuning the process, ground crews were able to unload planes in an average of thirty minutes. In 1949, one crew unloaded a C-54 Skymaster in a record time of 5 minutes 45 seconds.

But the position of Berlin remained precarious. In 1961, the city was again physically divided by the construction of a wall that remained until 1989.

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.