It has been 30 years since Communist rule in Eastern Europe finally ended with mass demonstrations, an end to one-Party rule, free elections and the opening of borders.

Illegal organisations, like the trade union Solidarity in Poland, formed governments. Jailed dissidents, like Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia, became Presidents. Long ruling dictators, like Romania’s Nicolae Ceauşescu, were toppled in days, and the Berlin Wall, the most potent symbol of the Cold War, opened.

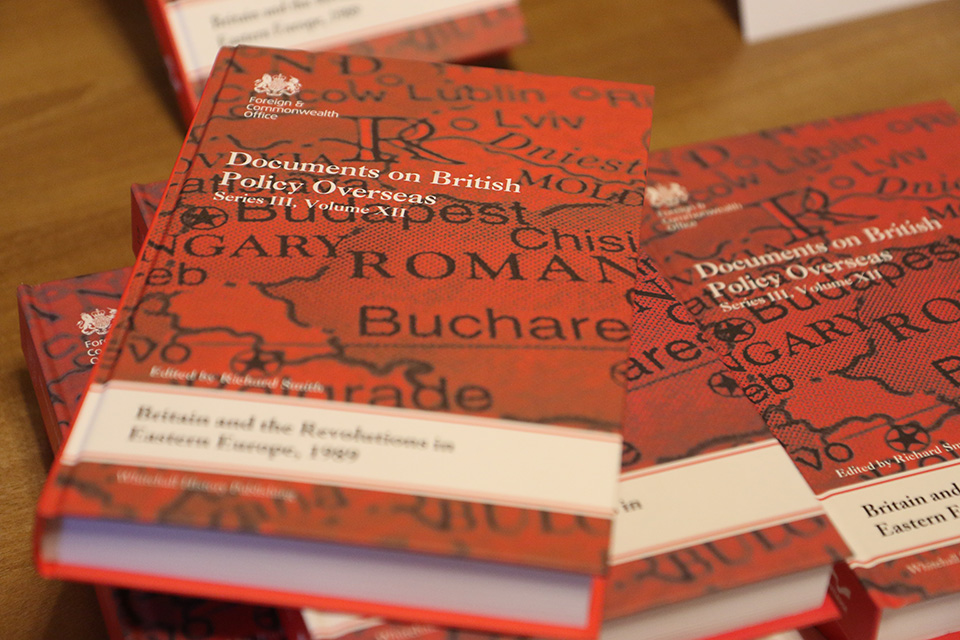

A new volume in the series Documents on British Policy Overseas (DBPO) charts the events of this historic year in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania. It contains reporting from British embassies on the rapidly changing political scene, and documents attempts in London to develop policy against the backdrop of unfolding revolution.

What was British policy?

From 1985, the UK adopted a new policy towards Eastern Europe, calling on diplomats to be more active in the region and to engage Western influence ‘in all areas and at all levels’. This aimed to encourage a gradual evolution away from Soviet influence.

Countries showing some independence from the Soviet pattern (primarily Hungary and Poland) were to be favoured but other countries should not be ignored, ‘just because they have nasty leaders’. Trade, economic reform, cultural engagement, human contacts and travel were all to be encouraged. Human rights were to be championed, even at the risk of damaging political relations.

The policy was a mixture of carrot and stick:

- encouraging political and economic reform with the promise of increased high-level contacts and economic assistance

- exploiting the attraction of Western societies and economies, and

- helping Eastern Europeans to change economically and politically

And this is what British diplomats enthusiastically set about doing – engaging with every section of society that the embassy could reach. Diplomats became well connected with dissident groups, which not only allowed them insight into current events, but also brought potential influence with new emerging post-Communist governments.

In some ways they were pushing at an open door. Popular calls for reform from within the Eastern bloc were legitimised by President Mikhail Gorbachev’s new policies of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness). They were emboldened by the Soviet Union’s increasing reluctance to intervene in the internal affairs of its Warsaw Pact allies. British officials returning to Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, after having served in the region in the 1960s and 1970s, noted this change.

There was now a momentum which British diplomats, through this policy of engagement and encouragement, were attempting to help along its way.

Change was not inevitable

But this momentum was not uniform. With hindsight there is a temptation to see events of 1989 as an inevitable chain reaction. Reading the documents, this was certainly not how it appeared at the time.

In March 1989 the FCO Planning Staff thought that although the governments in Hungary and Poland were now trying to ‘ride the wave of reform rather than fighting against it.’ The chances of seeing a genuine multi-party system with free elections were ‘extremely ambitious’.

The Cold War was still very much in evidence. In May, members of the Czech Embassy in London were expelled on spying charges and a visit by the Foreign Secretary to Prague cancelled. British officials, and Europe Minister William Waldegrave, were still assisting people caught trying to escape over the Berlin Wall, taking up their cases with the East German and Soviet authorities.

Providing assistance

In London, planning in early 1989 inevitably focused on Poland and Hungary, where the process of change was evident, where there was a clear direction of travel and time existed to devise and implement a strategy. Without the financial clout of the USA or West Germany to effect change, officials came up with innovative solutions to aid and support the transition they wished to see.

One such solution was the ‘Know-How’ Fund. This technical assistance programme aimed to transfer knowledge and skills in areas such as governance and management, financial services, law and justice, economic and monetary policy, and also political democracy. It funded carefully targeted initiatives in key areas where the UK had vast experience. There was a recognition that the UK had undergone a decade of economic restructuring and the new regimes in Eastern Europe were keen to learn from the British example. Again, it was about giving things a push in the right direction.

Making the most of Thatcher

By the autumn of 1989, Poland and Hungary both had non-Communist governments. British officials realised that they needed a new strategy towards Eastern Europe, looking ahead to the post-Communist era, and making the most of the Prime Minister’s popularity in the region.

Margaret Thatcher was the best asset the UK had. She was seen across the region as an uncompromising opponent of Communism, a champion of freedom and influential on the world stage. In February, she gave short shrift to a US proposal, inspired by Henry Kissinger, to seek an agreement with Gorbachev, over greater freedoms for Eastern Europe. She saw it as ‘an unwelcome element of super-power bilateralism, conducted over the heads of the Europeans’.

She herself was determined to take the lead amongst Western nations in supporting political change. Her November 1988 visit to Poland was seen as key to helping pave the way for the round table discussions between the Polish government and the trade union Solidarity the following year.

International partners

Britain was, of course, only one of many players and diplomats were determined that Western policy should remain as united as possible. This was especially true as the pace of change quickened with the fall of the Berlin Wall on the evening of 9 November. The Foreign Office set out how the European Community (EC) might manage its future relations with the region and developed proposals for EC economic support to ensure ‘the right positive response to the changes in Eastern Europe’.

Also of importance was the relationship with the Soviet Union. The British government was anxious that nothing should undermine President Gorbachev’s position. The government thought a change in the Soviet leadership would inflict major damage on the prospects for the further spread of democracy in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

Witnesses to change

As the year drew to a close, diplomats continued to report on increasingly dramatic events: the opening of the Berlin Wall, demonstrations in Wenceslas Square, fighting on the streets of Bucharest. On 13 December 1989, the eighth anniversary of the declaration of Martial Law in Poland, one diplomat in Warsaw noted that, Ceauşescu apart, Jaruzelski was the only East European leader at the beginning of the year who was still on top. ‘I wonder how many would have put their money on that in January’ he said – not knowing, of course, that by the end of year Ceauşescu would also be gone.

Sources:

Documents on British Policy Overseas: Series III, Volume XII: Britain and the Revolutions in Eastern Europe, 1989 (Routledge, 2020)

Witness seminar: British Embassies and the East European Revolutions of 1988–89

Transformational Diplomacy after the Cold War: Britain's Know How Fund in Post-Communist Europe, 1989-2003 (Routledge, 2013)

Keep tabs on the past: sign up for our email alerts

Follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians