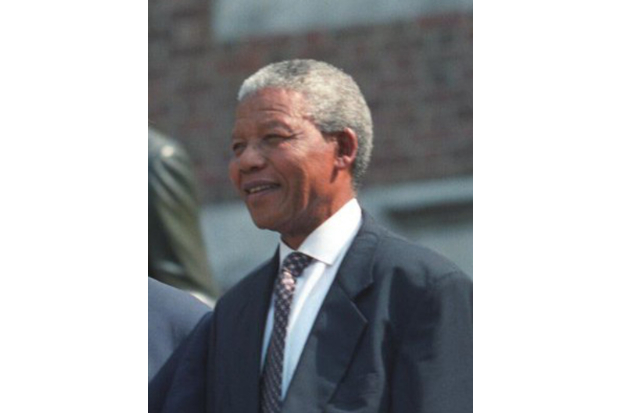

The release of Nelson Mandela from the Victor Verster Prison in Cape Town on 11 February 1990 was the most striking symbol of the end of apartheid in South Africa. His dramatic walk from the gates of the prison, hand in hand with his wife Winnie, captured the world’s imagination.

Mandela had been a prisoner for 27 years, arrested in 1962 and convicted in 1964 of conspiring to overthrow the state. For 18 of those years, Mandela endured the harsh conditions of Robben Island. By the late 1970s the almost invisible prisoner had become a symbol of South African oppression. During the 1980s ‘Free Nelson Mandela’ became a worldwide campaign.

His release was an act of political courage by the new South African president, FW de Klerk. But de Klerk’s decision, and its timing, were the culmination of decades of political, economic and social change that had brought apartheid to the brink of destruction.

A bankrupt system

The apartheid system was established by the Afrikaner-dominated National Party following its electoral victory in 1948. It was designed to enforce the ‘separate development’ of the white, black and coloured populations of South Africa, using a series of harsh laws and petty regulations, as well as inferior-quality education for black children.

In the 1960s black South Africans were deprived of their citizenship and forced to live in impoverished rural ‘Bantustans’. They had no right to settle permanently in the cities or near the mines where most of them worked. Yet South Africa’s wealth depended on those same workers, whose demands for better pay and conditions were becoming more vocal. Apartheid was beginning to fracture under the weight of its own contradictions.

Black resistance

Founded in 1912, the African National Congress (ANC) was nearly as old as South Africa itself.

In response to apartheid, a new generation of young activists such as Nelson Mandela organised a series of non-violent strikes and boycotts. These were met with arrests and the banning of both the ANC and the South African Communist Party (SACP).

After the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960, the ANC abandoned its policy of non-violence and launched a sabotage campaign; it was this that led to Mandela’s arrest.

By the 1970s, with many of its leaders in jail, the ANC was losing ground to the radical Black Consciousness Movement led by Steve Biko. In 1976, a strike of black schoolchildren in Soweto against the compulsory teaching of Afrikaans developed into a major uprising. A year later Biko died in prison as a result of multiple injuries. And the ANC was not alone: there were many peaceful protests led by the Churches and by the women’s Black Sash movement.

But a new wave of violent protests arose in the townships in 1984. It provoked the deployment of thousands of troops and the widespread use of terror tactics by both the government and its opponents.

Meanwhile, the ANC stepped up sabotage and armed attacks from its bases in neighbouring states. South Africa was becoming ungovernable.

The anti-apartheid movement

A British campaign to boycott South African goods launched in 1959 was renamed the Anti-Apartheid Movement after the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960. Led by Bishop Trevor Huddleston, it fought successfully to cut South African sporting and academic links with the rest of the world. Joined by similar movements across the world, its campaign to impose economic sanctions failed to persuade most governments banks and other businesses reduced or terminated their involvement in the South African economy.

Sanctions may not have had much direct impact, but white South Africans felt deeply their isolation from international cricket and rugby.

The Cold War

The Soviet Union’s commitment to world revolution helped to legitimise the South African government’s fight against the ANC at home, and its campaigns against Cuban forces in newly independent Angola and Mozambique.

After a prolonged stalemate, Cuban and Angolan forces achieved a major defensive victory over the South Africans at the battle of Cuito Canavale in 1988. As Gorbachev had come to power in 1985 and renounced Russia’s revolutionary ambitions, it was no longer credible for South Africa to portray the ANC as an agent of communism.

The Commonwealth

South Africa was expelled from the Commonwealth in 1961 but its members were increasingly determined to end apartheid. Sir Sonny Ramphal, Commonwealth Secretary General 1975 to 1990, took the lead in maintaining pressure on South Africa.

The Commonwealth agreed to ban sporting contacts at Gleneagles in 1977. A number of economic sanctions were also agreed at the Nassau Heads of Government Meeting in 1985 in the face of resistance from the British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher. In 1986 a Commonwealth ‘Eminent Persons Group’ visited South Africa and made recommendations that were rejected at the time, but formed the basis of the compromise achieved after 1989.

The South African government

Surprisingly at first sight, members of the South African government were aware by the late 1970s that apartheid would have to be reformed if it were to survive. Minor reforms began under the hardline former defence minister PW Botha (prime minister 1978 to 1984, state president 1984 to 1989) but these only provoked fiercer opposition.

Radical change came only when FW de Klerk became state president in 1989. Like Gorbachev in the Soviet Union, a reformer had emerged from within the system. A former hardliner, de Klerk realised that apartheid was politically, economically and morally untenable. But, like Gorbachev, de Klerk hoped to reform the system rather than overthrow it. One of his first actions was to order the release of Nelson Mandela. Between 1989 and 1994, he negotiated with Mandela and the ANC for an outcome that would preserve special rights for the white population, only to be ultimately outmanoeuvred.

The British government

Although all British governments were hostile to apartheid, they did not want to jeopardise Britain’s large economic stake in South Africa or provoke an exodus of up to a million British passport-holders.

In 1977, Labour Foreign Secretary David Owen started to take a tougher line. The South African government were relieved when the Conservatives came to power under Margaret Thatcher 2 years later, but they were wrong. Thatcher admired much of what white South Africans had achieved. She regarded the ANC as a terrorist organisation and was relentlessly hostile to economic sanctions. But she was not a racist. In her secret correspondence with PW Botha she kept up the pressure for change and called repeatedly for the release of Nelson Mandela.

Meanwhile, British diplomats reported on the terrible conditions in the townships and did what they could to support community efforts. In 1989 Britain’s Ambassador to South Africa, Robin Renwick, gave crucial support to de Klerk as he began to dismantle apartheid.

One person who bore no bitterness towards Margaret Thatcher was Nelson Mandela himself. They first met at No. 10 Downing Street on 4 July 1990. Having been asked to allow Mandela to speak without interruption for at least half an hour, since he had waited 27 years to tell his story, Thatcher listened to Mandela for over 50 minutes (‘possibly a record’, her private secretary Charles Powell remarked).

Sources and suggestions for further reading:

Documents on British Policy Overseas, Series III, Vol. IX, The Challenge of Apartheid: UK-South African Relations, 1985 to 1986 (2017)

Documents on British Policy Overseas, Series III, Vol. XI, The Unwinding of Apartheid: UK-South African Relations, 1986 to 1990 (2019)

Saul Dubow, Apartheid, 1948 to 1994 (2014)

Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom (1994)

Robin Renwick, A Journey with Margaret Thatcher: Foreign Policy under the Iron Lady (2013)

Anthony Sampson, Mandela: The Authorized Biography (rev. ed. 2011)

Keep tabs on the past: sign up for our email alerts

Follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians