Forty-five years ago this month 35 nations signed the Helsinki Final Act following the 2-year Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE). A politically binding agreement, the Final Act consisted of 3 ‘baskets’ containing a broad range of measures designed to reduce Cold War tensions, and marked the highpoint of détente in Europe.

Basket I contained a Declaration of Principles Guiding Relations between Participating States (including an all-important Principle VII on human rights and fundamental freedoms). Basket II covered economic, scientific, technological and environmental co-operation. Basket III was devoted to co-operation in humanitarian and other fields: freer movement of people; human contacts; freedom of information; and cultural and educational exchanges.

Principle VII and Basket III together became known as ‘The Human Dimension’. Whilst the significance of the Helsinki Final Act in helping to end communism in Eastern Europe has been debated, what is clear is that there would have been no Human Dimension in the Final Act were it not for the policies pursued, and the tactics employed, by the West at the multilateral preparatory talks (MPT) which preceded the CSCE.

Setting the stage

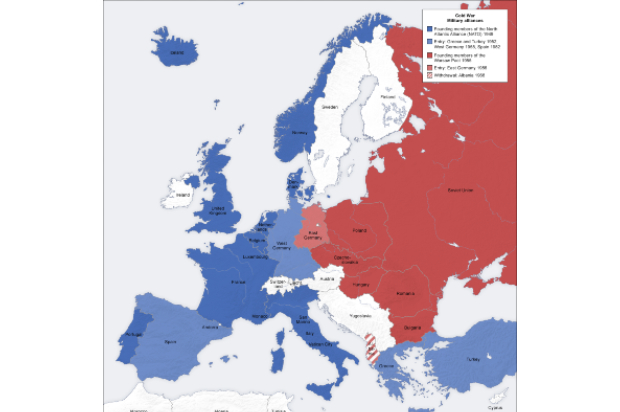

A conference on European security and cooperation had a long history. The Soviet Union had first proposed one in the 1950s to settle post-war problems, particularly in relation to Germany and Berlin, and obtain recognition for the post-1945 political boundaries in Eastern Europe. However, it was not until the early 1970s that the international situation allowed preparatory talks for such a conference to take place.

British officials were initially unenthusiastic. The general view was that the Soviet Union intended to use the conference to reinforce its hegemony in Eastern Europe, disrupt the economic and political integration of Western Europe, weaken NATO, and secure commercial advantages and greater access to Western science and technology.

Soviet détente initiatives rang hollow in the face of sustained and widespread intelligence activities within Britain. In September 1971, in an unprecedented move, the government found it necessary to expel 105 Soviet officials from Britain in order to check this activity (Operation Foot). However, as the realistic prospect of a conference grew Foreign and Commonwealth Office officials decided to try to use the occasion to turn the tables on the Russians.

Enter the ‘whippersnappers’

The British delegation to the MPT consisted mainly of young high-flying First Secretaries who brought both energy and ability to the negotiations. Their lack of seniority annoyed the Russians—who sent ambassadorial level officials—but this was deliberate. As George Walden, one of the British delegates, recalled: ‘One of the reasons we sent whippersnappers like us was to show our scepticism... And of course, being whippersnappers, we were quite keen to sort of bounce around in the way that inexperienced youth tends to do.’1

The ‘whippersnappers’ would need all their energy over the 199 days of discussions between 22 November 1972 and 8 June 1973, carried out in plenary sessions, working groups, corridor conversations, and even the bar of the Students’ Union where the talks were held. As Walden recalled: ‘we waited for spring to arrive, and it never did.’2

A natural cynicism towards Soviet rhetoric, the recent success of Operation Foot, and a certain fearlessness all served to fire up the British negotiating team. They were determined to see more emerge from the conference than merely a Soviet consolidation of the division of Europe. They wanted to find ways to expand the discussion into areas such as the free movement of people, ideas and information – areas traditionally outside the Russian comfort zone.

‘So we went out there—yes, sceptical—and, if you like, a bit aggressive on the subject, but I have to say when I look back what I recall is really how exhilarating the whole process was,’ recalled Andrew Burns, another member of the team. ‘It was the hunt; the chase. For the first time we were able to discuss issues openly with the Warsaw Pact countries, issues which they always tried to keep off the table.’3

Like others on the team, George Walden had lived in the Soviet Union and found it a dispiriting experience. ‘So we got stuck into this conference, saying, “Why don’t you have freedom of information?” asking these absurd questions that no-one would normally ask of the Russians. It was seen as somehow indelicate to bring these matters up. We persisted in doing that and . . . we had help from a lot of other delegations who were similarly, when roused, hostile to the Russians.’4

The end of the beginning

Western success in the preparatory talks was put down to careful advance preparations carried out in NATO and the European Communities, the maintenance of cohesion during the talks, and winning the sympathy and support of neutral countries. But a key Western tactic was not to commit to a conference unless they were satisfied the results of the preparatory talks warranted it.

‘It was very clear,’ recalled deputy head of the British delegation, Brian Fall, ‘that the Russians wanted the preparatory talks, if there had to be preparatory talks, to last a week and a half, to agree the agenda, date, and place for the conference proper, and then to go for it. We were arguing that we wouldn’t go to a conference unless we had reasonable expectation that there would be scope for detailed discussion of the subjects we thought important, and the prospect of worthwhile conclusions.’5

In the end the Russians fought hard for a more restrictive agenda but ultimately had to give way when they realised it was the price they had to pay in order to have any conference at all.

The West had managed to turn the Soviet desire for a short conference, focussing on high-level political declarations, into a three-stage conference, with time for substantive discussion on Human Dimension issues.

With the agenda and procedures fixed by the MPT the Soviets never fully regained the diplomatic initiative, despite several attempts, during the Conference proper. In this sense, the pre-conference talks were key to shaping the provisions of the Final Act. It is impossible to appreciate what was achieved at Helsinki without an understanding of the preparatory negotiations.

To mark the anniversary, FCO Historians have published an account of the MPT, written by Brian Fall: Preparing for Helsinki: The CSCE Multilateral Preparatory Talks. View a digital version on the FCO Historian’s Issuu page or you can buy a copy.

Keep tabs on the past: sign up for our email alerts

Follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Office Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians