We’ve got to have this thing over here, whatever it costs. We’ve got to have the bloody Union Jack on top of it.

“This thing” as British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin put it, was the Atomic Bomb. Bevin was quoted thus by Sir Michael Perrin, formerly deputy to Lord Portal who was Controller of Production, Atomic Energy, in a BBC Timewatch programme on 29 September 1982.[1] This blog recalls the international and domestic factors that Clement Attlee's government had to weigh in the balance when coming to this historic decision.

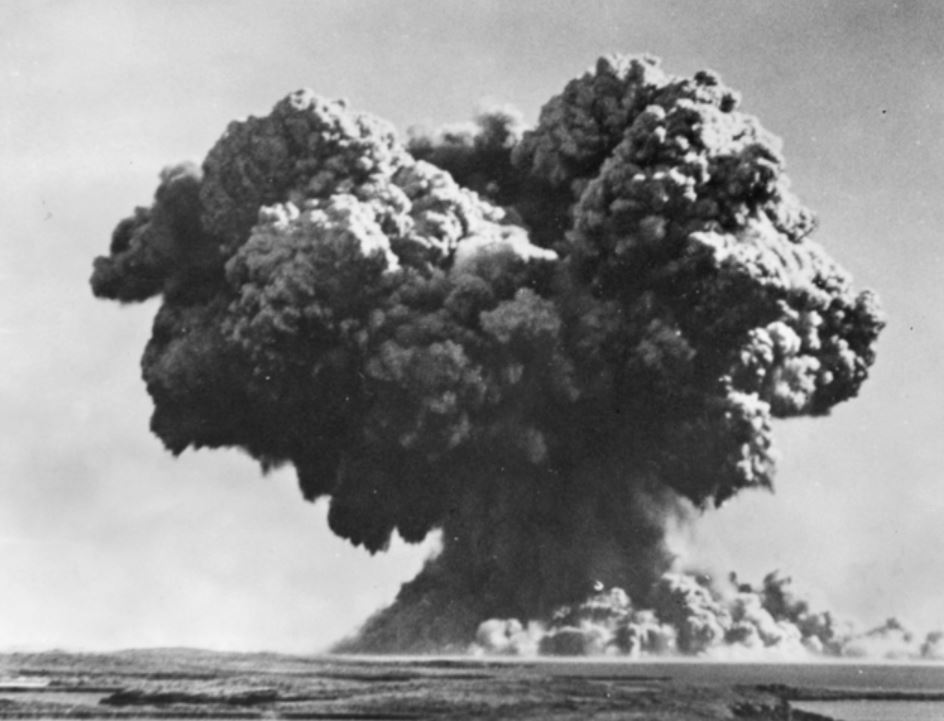

Seventy-Five years ago a small group of government ministers agreed that research and development on atomic weapons should be undertaken in the UK, under conditions of special secrecy. It was a decision both momentous and essential. Momentous because it was taken against the wishes of Britain’s closest ally the United States, and because it committed huge government resources that Britain could not afford. It was essential because although no atomic weapon would be ready for 5 years, to ensure a future national capability for deterrence or retaliation the decision could not wait. The same has been true of all subsequent decisions to replace or renew atomic weapons systems. Such decisions are always controversial and difficult, but they are also impossible not to take.[2]

The decision in January 1947 formalised what many had assumed ever since the use of the first atomic weapons against Japan in August 1945. When Churchill, now Leader of the Opposition, said in Parliament in November 1945 ‘This I take it is already agreed, we should make atomic bombs’, no one challenged him. As Peter Hennessy puts it, there was an ‘atomic bias’ in all the deliberations of GEN 75, the ministerial committee set up in August 1945 to deal with atomic matters.[3] Yet it was not until 8 January 1947 that the decision was taken, not by GEN 75 but by a specially convened ministerial committee GEN 163 at its sole meeting; and the context was complex.

We ought not to give the Americans the impression that we cannot get on without them; for we can . . . and, if necessary, will do so.[4]

Although Ernest Bevin’s comment about the Union Jack on Britain's own bomb catches the eye, Prime Minister Clement Attlee was the prime mover on nuclear issues in the postwar Labour government. Convinced that the atomic bomb changed the whole calculus of future warfare, he had been pressing President Truman since August 1945 for cooperation and international control. He received soothing responses but little more. The bomb had been developed through wartime cooperation between British, Canadian and US scientists. But hopes of postwar collaboration were dashed by US determination to control access to the ‘atomic secret’. The McMahon Act passed by Congress in August 1946 prohibited sharing nuclear information, even with close allies. The Truman administration also hoped to use the nuclear monopoly as leverage with the Soviet Union.

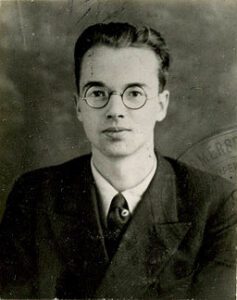

The Americans argued that a nuclear plant in the UK would be ‘insecure’ and incompatible with proposals for international control under discussion in the UN Atomic Energy Commission. Attlee rejected these arguments, but the US context was not simple either. There was much political in-fighting, with some Republicans determined to discredit the late President Roosevelt and any ‘secret’ wartime agreements. The military wanted exclusive control of any weapons, and many Americans remembered the Canadian spy scandal exposed in 1946, when a British atomic scientist was revealed as a Soviet agent. But the Americans also knew that Britain would be able to draw on the expert knowledge of scientists (including Klaus Fuchs)[5] who were now returning to the UK after working on the Manhattan Project. This made the British the next most likely country to be able to develop an atomic weapon. Helping Britain to do so was not considered to be in US interests.

Attlee did not give up on Anglo-American collaboration. But he, like Bevin, was determined Britain should have its own bomb and insisted the decision to site a nuclear plant in the UK was for the British, not the US government to take. It was not just a question of prestige or in hope of securing American cooperation. Ministers took their decision knowing that Britain’s financial situation was desperate and the government could not afford the major financial commitment involved. It was no coincidence that spending ministers were not present at the meeting. Many factors were straining British resources, whether to fund domestic reform or meet global military and financial commitments. These factors also made it seem vital that Britain should embark on nuclear research and development that would both protect the nation and fuel industrial recovery.

At home, there were concerns about communism. Two days before the nuclear decision, another ministerial committee set up a Cabinet Committee on Subversive Activities.[6] Overseas, although East-West tension had not yet solidified into open enmity, the international scene looked menacing enough. Bevin was engaged in a series of adversarial negotiations on peace terms, regional influence and access to resources, recognising Soviet resentment at what it saw as exclusion from the spoils of war even as he despaired of Russian intransigence. Ministers were well aware of Soviet interest in the atomic bomb, even if they did not realise how much information had already reached Moscow through agents like Fuchs and Maclean. That made a British bomb even more necessary.

The decision of 8 January 1947 was taken in the context of vulnerability, an aspiration to independence and a determination to secure Britain’s future. This context trumped all, including the fact that a commitment to an expensive nuclear future could not be justified economically. Mutual defence arrangements under NATO were more than 2 years in the future. For now, "if Britain wanted to be sure of being covered by an atomic deterrent, she had no option to make it herself."[7]

Sources for further reading

[1] The formal minutes of the meeting on 8 January 1947 are printed in Documents on British Policy Overseas (DBPO), Series I, Vol. XI, No. 36, and record Bevin’s views in a more measured way. See also Peter Hennessy, The Secret State: Preparing for the Worst 1945-2010 (Penguin revised edn, 2010).

[2] See Matthew Jones, The Official History of the UK Strategic Nuclear Deterrent, Vol. I, From the V Bomber Era to the Arrival of Polaris, 1945-1964 (London: Routledge, 2017).

[3] Hennessy, Secret State, p. 49. On GEN 75 see DBPO, Series I, Vol. II.

[4] Message from Attlee to Bevin (who was in New York), 27 November 1946: DBPO, Series I, Vol. VII, No. 97.

[5] Fuchs was exposed as a long-term Soviet agent in 1950: see https://history.blog.gov.uk/2020/03/02/whats-the-context-sentencing-of-atomic-spy-klaus-fuchs-1-march-1950

[6] Minutes of GEN 164/1, 6 January 1947, printed in DBPO, Series I, Vol. XI, No. 35.

[7] Margaret Gowing, Independence and Deterrence: Britain and Atomic energy, 1945-1952, Vol. I, Policy Making (London: Macmillan, 1974), p. 185.