On 20 February 1913 The Times reported: ‘An attempt was made yesterday morning to blow up a house which is being built for Mr Lloyd George near Walton Heath Golf Links’. One device had exploded, causing about £500 worth of damage, while another had failed to ignite.

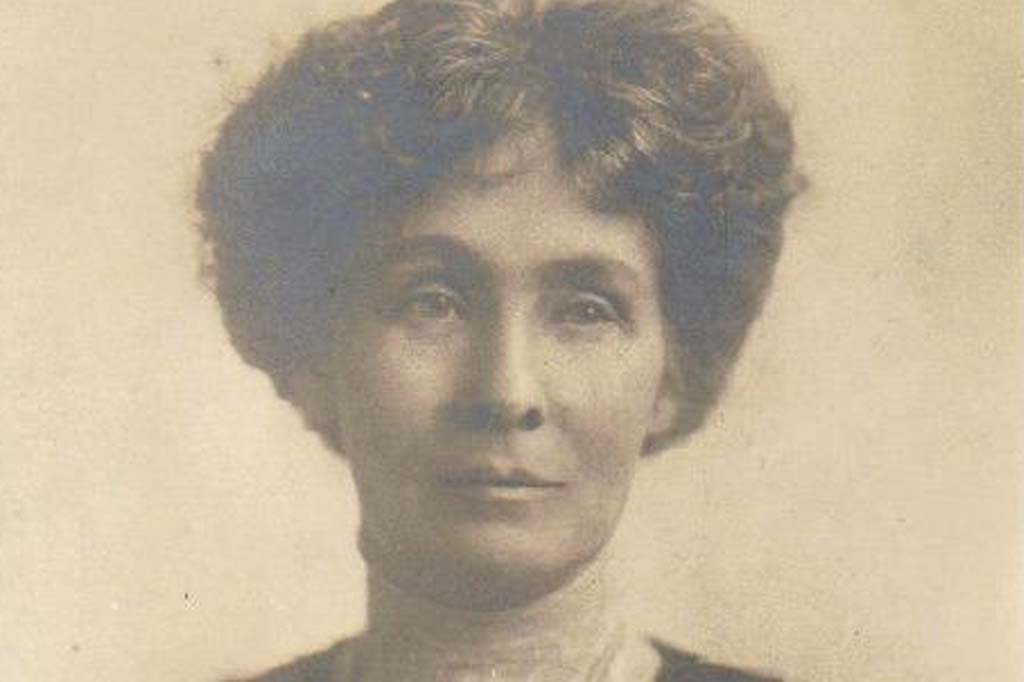

With discarded hairpins, hatpins and the sound of a motor car as their only clues, it was fortunate the police soon had a confession. For that evening, at a meeting held in Cory Hall Cardiff, Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst, one of the leaders of the militant suffragette society, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), declared ‘we have blown up the Chancellor of Exchequer’s house’ and stated that ‘for all that has been done in the past I accept responsibility. I have advised, I have incited, I have conspired’.

Attacks on property and pleasure

The government had been waiting for this moment for over a year. During that time suffragette speeches had been transcribed, phrases that might be deemed inflammatory were underlined and the prospects of prosecution carefully weighed in the hope of instigating legal action against the WSPU leaders. February 1913 marked a new stage in the women’s suffrage campaign for, as Mrs Pankhurst threatened in her Cardiff speech, the WSPU was now prepared to attack the things she considered most valued by contemporary society – ‘money, property and pleasure’. ‘Militancy was right’, Mrs Pankhurst concluded, because ‘No measure worth having has been won in any other way.’

In the early stages of the campaign, militants had confined their attacks to government property, but from 1911 onwards had begun to attack private property. At first this had been confined to smashing shop windows and setting fire to letter boxes but, as frustration with the government’s refusal to concede votes for women mounted, these attacks became increasingly violent and spectacular. In 1913 the militants began a concerted arson campaign, which included setting fire to residential houses, golf courses, schools and even churches. The bombing of David Lloyd George’s house was part of this campaign.

Bombs concealed in cupboards

More recent experience of domestic terrorism suggests the bombing of Lloyd George’s house should be reconsidered. The WSPU always insisted that their actions would never harm individuals and, like the many other buildings they attacked, this house was uninhabited; but a slight miscalculation might have led to a different outcome. Workmen had been due to arrive at the house around 6am, and the primitive fuses used could easily have resulted in the bombs exploding after their arrival. Indeed, after visiting the house with the Lloyd Georges to see the bomb’s impact, Sir George Riddell, the proprietor of the News of the World, who had commissioned the house, wrote on 4 March in his diary:

‘LG much interested. Said the facts had not been brought out and that no proper point had been made of the fact that the bombs had been concealed in cupboards, which must have resulted in the death of 12 men had not the bomb which first exploded blown out the candle attached to the second bomb, which had been discovered, hidden away as it was. He was very indignant…’

Shortly after the bombing Emmeline Pankhurst’s daughter, Christabel, was interviewed by the Daily Chronicle in Paris, where she had gone to escape prosecution back home. In response to the reporter’s question, ‘Aren’t you afraid of being called Anarchists?’, Christabel made the WSPU position quite clear: ‘We do not mind at all …we are fighting a revolution’. She explained that Lloyd George was a prime target because, while often professing himself in favour of women’s suffrage, ‘he is always betraying us’. This was a reference to the repeated collapse of attempts by Lloyd George to effect a reconciliation between the Liberal Government and the suffrage movement: something that militants attributed to insincerity on his part.

Perpetrators never caught

It was no secret that the house being built at Walton-on-the-Hill was intended for Lloyd George. However, he had not yet signed the lease and, when the explosion occurred, had already set out on a motoring holiday in the south of France with Sir Rufus Isaacs, the Lord Chief Justice. Like Lloyd George and other Liberal luminaries, such as Reginald McKenna and Charles Masterman, Rufus Isaacs was a member of the Walton Heath Golf Club, of which Sir George Riddell was a director. Sir George was an intimate friend of Lloyd George and the club was his power base. Over a round of golf newspaperman and politicians could discuss the issues of the day, retiring later to their country houses nearby. The masculine exclusivity of this circle was a goad to militant suffragettes debarred from the world of parliamentary politics. Although police suspected two WSPU members, Olive Hockin and Norah Smyth, the perpetrators were never caught.

By claiming responsibility for the bombing, Mrs Pankhurst reduced pressure on the Home Office to bring the real culprits to trial. Her Cardiff meeting was attended by a large force of police and her speech transcribed by a reporter of the Western Mail, the proprietor of which was none other than Sir George Riddell. The Mail’s editor assured the chief constable that the shorthand taker had kept his original notes and would be available to give evidence. At a meeting on 21 February in the office of the Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, the decision was taken to prosecute Mrs Pankhurst for procuring and inciting women to commit offences contrary to the Malicious Injuries to Property Act, 1861. She was arrested on 25 February, on 3 April was sentenced to three years’ penal servitude and immediately went on hunger strike. No attempt was ever made to feed her forcibly and the Prisoners’ (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Bill’, which allowed hunger-striking prisoners to be released to recover their health before being returned to prison, was rushed through to ensure that she did not die in prison. Notorious as the ‘Cat and Mouse’ Act’, the Bill received the Royal Assent on 25 April.

Militant campaign suspended during wartime

From then until the outbreak of war in 1914 the idea that women might wish for a parliamentary vote on the same terms as men, launched so innocuously in 1866 with one petition to Parliament, was to foster a spiralling succession of destructive acts that left their perpetrators either outlawed or imprisoned, on hunger strike and forcibly fed, and gave the government ever more reason to pursue the WSPU’s organizers, its supporters and, most importantly, its funds.

In August 1914 the WSPU suspended its campaign, writing to its members that ‘even the most vigorous militancy’ was ‘rendered less effective by contrast with the infinitely greater violence done in the present war’ and that non-militant campaigning was futile ‘even under ordinary conditions’. This was not, however, the view taken by the constitutional societies. They, too, initially suspended campaigning but during 1917, after Asquith, who had always been intransigent over ‘votes for women’, had been replaced as prime minister by the more sympathetic Lloyd George they took the opportunity to lobby the coalition government to ensure that women - or at least those over the age of 30 - were included in a new Representation of the People Bill.

On 5 February 1918, almost exactly five years after a bomb had exploded in his house, Lloyd George was the prime minister at the head of the government that for the first time allowed women not only to elect MPs but also to stand for election to Parliament.

Remember, if you're not on the electoral register, you don't get a say in who runs the country and how. Register to vote today

Suggested further reading

J.M. McEwen (ed), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (1986)

Roy Hattersley, Lloyd George: the great outsider (2010)

Paula Bartley, Emmeline Pankhurst (2002)

Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement: a reference guide (1999)

Biography of David Lloyd George

Copyright Elizabeth Crawford. This article was produced as part of the No10 Guest Historian series, coordinated by History & Policy.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.

5 comments

Comment by Ann Taylor posted on

Family legend has it that my grandmother and her sister had signed on to be suffragettes. Where would I find this infoirmation? Apparently, they were the first Cardiff women to do so. Ann Taylor

Comment by Mark Dunton posted on

Hi Ann, thanks for your message. Your best course of action, in the first instance, is to contact the Women's Library at the London School of Economics, as they hold a superb collection for the Suffragette movement. Here is a link to their contact details: http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/a/A13530202 You may also require the services of The National Archives at a later stage in your research: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk Best wishes, Mark

Comment by Gemma posted on

Could you please correct the spelling mistake of Emmeline's name in the photo caption?

Comment by Mark Dunton posted on

We have done so -thank you for pointing this out Gemma.

Comment by peachie posted on

Emmeline Pankhurst was HARSH!