‘The most powerful government ever to fall as a result of American covert action was the administration of Richard Nixon’

Christopher Andrew, For The President’s Eyes Only

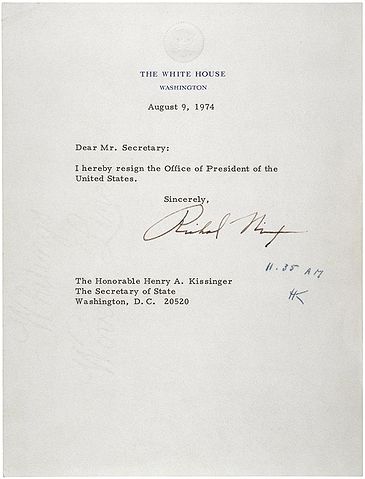

Forty years ago, on the evening of Thursday, 8 August 1974, the 37th President of the United States addressed the nation in a television broadcast and announced that he was resigning with effect from noon the following day. On 9 August, Vice President Gerald Ford—who had himself only taken office in October 1973 when the previous incumbent had resigned when charged with bribery, conspiracy and tax fraud—succeeded to the most powerful job in the world.

Political Ruin

So ended the process of political ruin that began with the discovery in June 1972 of a burglary at the offices of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate building in Washington, carried out by ham-fisted covert operatives whose activities were traced back to the Republican White House and eventually to the President himself, despite elaborate efforts at concealment and misdirection. Investigations revealed a complex web of dirty tricks and covert operations authorised by Nixon and his close advisers, implicating all organs of the US government and intelligence establishment, and dating back long before Watergate. Now, as Jonathan Schell wrote in an illuminating series of New Yorker articles in 1975: ‘The body of secret information which had begun to build up in the White House as far back as the Kennedy years had grown to a size that was unmanageable within the framework of a Constitutional democracy.’

Incriminating tape recordings

The Supreme Court ruled at the end of July 1974 that executive privilege was not unlimited, and that Nixon must surrender incriminating tape recordings—recordings he himself had ordered, obsessed with memorialising every detail of his presidency; he employed an army of ‘anecdotists’ as well as taking his own notes. The contents of the tapes finally destroyed Nixon’s credibility and led most of his Congressional supporters to vote in favour of impeachment. Even Henry Kissinger, his Secretary of State, National Security Adviser and close friend, had told him on 6 August that he should go: an impeachment trial would paralyse foreign policy and demean the Presidency.

Faced with all this, Nixon decided to resign. By this time, successive revelations meant the decision was not unexpected and caused surprisingly few ripples across the world: most British political diaries and memoirs fail to mention it at all, while in the Soviet Union, where Nixon had visited only 6 weeks before, President Brezhnev fretted only that Nixon’s disgrace might weaken his own reputation. But the resignation of a US President, leader of one of the world’s two Cold War superpowers, was a unique event nevertheless.

Achievements

‘I have never been a quitter’, Nixon said in his broadcast, but ‘as President I must put the interest of America first’. Though apologetic up to a point, expressing regret for ‘any injuries that may have been done in the course of the events that led to this decision’, he was not reticent about his achievements.

Since becoming President in 1969 he had, he claimed, ended ‘America’s longest war’ in Vietnam by the agreement signed with North Vietnam in January 1973; ‘unlocked the doors’ between the USA and Communist China by his groundbreaking visit in February 1972; achieved a limited degree of peace in the Middle East, still in turmoil after the Yom Kippur war of October 1973 (including, crucially, Saudi agreement to resume oil sales to the US); and signed an important arms limitation agreement (SALT 1) with the Soviet Union in 1972.

Though some of these achievements were incomplete or hedged with qualifications, they were nevertheless considerable. As Christopher Andrew puts it, ‘The Nixon-Kissinger combination was arguably the most talented ever to run American foreign and security policy.’ And though the idea has become a commonplace that preoccupation with Watergate took Nixon’s eye off the ball in both domestic and foreign policy during the 18 months before his resignation, the evidence does not entirely support this.

It is easy to say what Nixon ‘would have done’ in a particular situation if not distracted: but impossible to prove. Who is to say inaction or delay was not a deliberate policy choice? For example, when Nixon and Kissinger resisted pressure from British Foreign Secretary James Callaghan to take a tough line in the Cyprus crisis in July 1974, the evidence suggests their reluctance was rooted in a calculation of US interest, rather than a lack of interest.

Global instability

The context of Nixon’s resignation was a high degree of global political and economic instability in which the energy crisis caused by the Middle East war of 1973 and an Arab oil embargo against the western powers was a major factor.

1974 saw a number of game-changing events, including the Turkish invasion of Cyprus and the downfall of the Colonels’ regime in Greece; the fall of the Caetano regime in Portugal and the end of Portuguese colonial rule in Mozambique; the failure of Kissinger’s ‘Year of Europe’ and a fractious relationship between the US and Europe in which the British government, in its first year of EEC membership, found itself in the familiar position of piggy in the middle.

Significant figures other than Nixon left the world stage in 1974. Some exits were permanent: in France, the death of Georges Pompidou in April brought the Gaullist era to an end, and the Presidency to Giscard d’Estaing; in Argentina, the veteran President Juan Peron was succeeded by his second wife, Isabel; in West Germany, the resignation of Willy Brandt over a spy scandal made Helmut Schmidt the new Chancellor; and in Ethiopia, riots and student protests so undermined Emperor Haile Selassie that he was deposed in September. Other departures were temporary: President Makarios of Cyprus, ousted in a Greek coup in July, was to return to office in December; in Spain, the ailing dictator General Franco handed over power to Prince Juan Carlos - but only for a few months; and in Libya, the erratic Colonel Qadafi was relieved of day-to-day duties by the Revolution Command Council in order to concentrate on the ‘ideological direction’ of the Libyan people - but remained head of state.

Shocking contrast

Against this context, Nixon’s resignation may seem just one more shifting pattern in the kaleidoscope. But 40 years later, the contrast still seems shocking between the President’s experience, abilities and undoubted flair for international affairs, and the depth of his disgrace. Nixon was wracked by insecurity and believed that the only way to succeed in politics was to get your retaliation in first: at some point, he lost the ability to distinguish between threat and reality, executive power and contempt for the law.

For Jonathan Schell, there was a direct causal connection between the Vietnam war and Watergate: one of Nixon’s first acts as President was to order a secret bombing campaign against neutral Cambodia. For Richard E. Neustadt, Nixon, like his predecessor Lyndon Johnson, was ‘a driving man and driven, tending to excess, compulsive in seeking control, taking frustration hard’. But we should give the last word to Henry Kissinger, who knew him better than most: ‘It was impossible to talk to Nixon without wondering afterward what other game he might be engaged in at the moment. Of one thing you could be sure. No single conversation with Nixon ever encapsulated the totality of his purpose.’

Suggestions for reading:

Henry Kissinger, Years of Upheaval (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1982)

Documents on British Policy Overseas, Series III: Vol. IV, The Year of Europe: America, Europe and the Energy Crisis 1972-74; Vol V, The Southern Flank in Crisis, 1973-76 (London: Routledge, both 2006).

Richard E. Neustadt, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents: The Politics of Leadership from Roosevelt to Reagan (London: Macmillan, revised edn 1980)

Christopher Andrew, For the President’s Eyes Only: Secret Intelligence and the American Presidency from Washington to Bush (London: HarperCollins, 1995)

Jonathan Schell, ‘Reflexions on the Nixon Years’, 6 articles in the New Yorker, 1975; cited here, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1975/06/30/the-time-of-illusion-v-the-script-and-the-players

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.