‘In an office like ours, which is engaged solely on war work, it is often a matter of extreme difficulty to decide whether a man’s duty is to remain in his present post or to join the Army’ (National Archives reference: PRO 1/80)

This sentence from a letter written by an Admiralty official in 1915 sums up the dilemma faced by the ‘front line’ government departments during the First World War - at that time established staff needed permission to join up, but when conscription was introduced in the following year the problem became even more acute.

The challenges were only just beginning…

The First World War was the first ‘total’ war – virtually all sectors of society had to be ‘mobilised’ and the nation’s resources harnessed for the war effort. The Civil Service, like every other employer, had to deal with losing staff to the armed forces, and finding replacements to do their work while they were away. Some of these replacements were women, and others were recently retired staff being recalled for the duration. But covering the work of civil servants who were away on active service was just the beginning of the challenges faced by government departments. Most of them had to deal with new, often unforeseen, problems arising from the war, and had greatly increased workloads as a result.

The General Register Office may not look like an obvious ‘front line’ department, but it had to cope with an upsurge in applications for marriage certificates from the wives of servicemen, who needed them to claim separation allowances, or widows’ pensions. Inevitably, there were also hundreds of thousands of extra deaths to be registered. This affected the Probate Department too, who had to deal with huge numbers of extra wills and letters of administration as a result of these war deaths. Then there was the additional problem of dealing with estates where the beneficiaries were resident in countries with whom Britain was now at war.

New responsibilities, new departments

The War Office and Admiralty obviously had a war to run, but other departments also had greatly increased workloads. The Board of Trade and the Ministry of Labour had to ensure that industry was directed to war production, the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries was responsible for maximising food production, and the Ministry of Transport was of vital importance in getting troops, supplies and post to where they needed to be, quickly and efficiently. The war also led to the creation of entirely new departments, like the Ministry of Munitions and the Department (later Ministry) of National Service. The many responsibilities of the Home Office included law and order and security at home, including the treatment of enemy aliens. Some of these were widows of German or Austrian men, who now had to apply for naturalisation to regain their British nationality, so as not to be treated as enemy aliens themselves. And as ever, the approval of the Treasury was needed to ensure that all this extra activity could be paid for.

These are just some of the government departments who had to rise to the challenge of getting the country on a war footing in Whitehall and around the country. The National Archives holds a huge collection of records dealing with these and other departments, many of them under-explored. The records vary enormously from department to department, but together they paint a vivid picture of how civil servants reacted to the war emergency.

‘Overwhelmed departments’

The first item in the Public Record Office’s general correspondence for 4 August 1914 is from a senior clerk volunteering his services since ‘…it is likely that some of our staff may be lent to the War Office and other overwhelmed departments’ (The National Archives reference: PRO 1/79). He and several other clerks from departments not directly involved in war work were indeed lent to the War Office and the Admiralty for the duration. But even though they had no increased volume of work due to the war, organisations like the PRO and London’s museums and galleries had to take steps to protect their valuable collections in case of Zeppelin raids, as well as maintaining at least a minimum ‘business as usual’ service, with fewer staff.

A 1915 report in Board of Trade papers echoes the concerns of the Admiralty: ‘In the case of the Board of Trade it might be much more important to keep a Labour Exchange working to supply labour for transport, trench digging and other purposes, than to obtain the slight addition to military strength resulting from the Labour Exchange manager and clerks joining their local Volunteer Corps’ (The National Archives reference: BT 13/61). When conscription was introduced in 1916 it became even harder for departments to retain experienced members of staff. They also had to deal with the sometimes hostile attentions of the press – the Daily Mail of 30 May 1916 accused single men in the civil service of ‘sheltering under the government umbrella’ while married men were being called up from elsewhere.

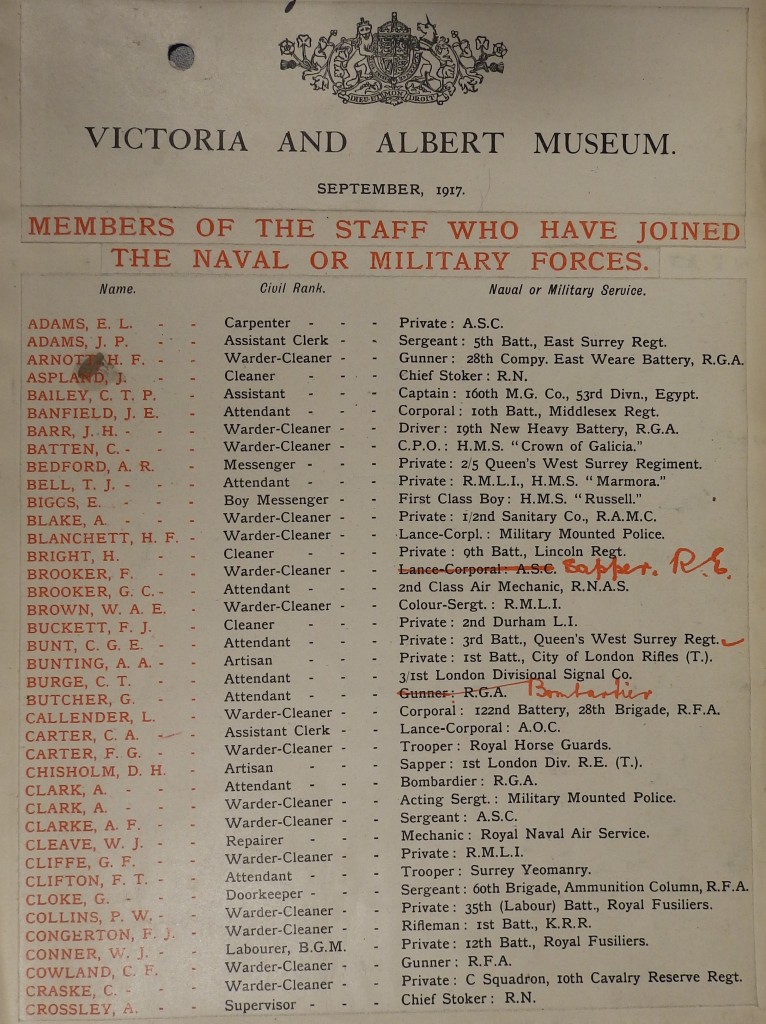

The records of every department contain discussions on staffing, often including lists of names. Many made lists of their staff of military age, sometimes with additional information. The Supreme Court kept a Staff Book from 1841 to 1935, with a page for every member of its central office staff. These give dates of birth, appointments and promotions, and of retirement, resignation or death. For those who served in the First World War the details of their war service are noted, including the units where they served and the rank they held. In 1917 the Victoria and Albert Museum produced a list of their staff currently serving in the forces, with an accompanying typescript list giving even more detail.

The records of men who served in the armed forces can be researched in records of the respective services, albeit with some difficulty in the case of the army, since many records have been lost. Men who died in service are particularly well-recorded, thanks to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and others. However, research in the records of many government departments has uncovered a surprising amount of information about many civil servants who did not take up arms, or wear a uniform, but who made their contribution to the war effort in other ways.

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.