The early years of the First World War brought a large number of casualties to the army of Great Britain and despite the number of volunteers the government was soon in dire need of more troops. On the 2nd March 1916 the Military Service Act came into force. This Act enforced compulsory military service for every British male aged between 18 and 41 who was either unmarried or a widower without children (later Acts widened the range of men eligible and altered the age qualification). Exemption could be granted from this conscription into the military forces by means of a Tribunal system.

Reasons for objecting

For millions of British citizens, conscription was a controversial issue, especially for those who had strong anti-war convictions. Conscientious Objectors had many reasons for objecting. Those who objected on moral grounds became Conscientious Objectors. A pacifist who objected to war in principle and therefore refused to be enlisted was considered a Conscientious Objector. Others had political objections to the war as they did not consider the government of Germany to be their enemy. Some had religious objections to the war, believing whole-heartedly in the commandment 'thou shalt not kill'. Members of religious groups such as Quakers or Jehovah's Witnesses fell into this category.

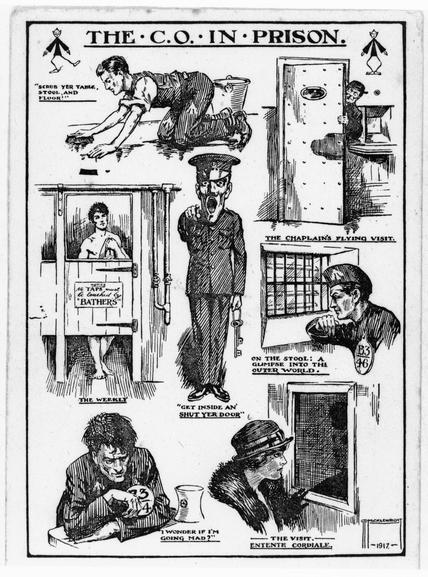

As with those wishing to be exempted from fighting for reasons of employment, family needs or disability, Conscientious Objectors had to attend a Tribunal hearing to register their objection to participating in combat. If a man's job was considered valuable to the war effort, he was exempted from enlisting. The cases of Conscientious Objectors, however, were usually rejected. Those who had been rejected were forcibly enlisted in a combatant Corps, although some could opt to join the Royal Army Medical Corps. If the Objector refused to don the uniform and cooperate he would be sent to prison where the conditions were harsh. Albert Leverson James (1887-1917), of Kingston, was one such man.

The sad story of Albert Leverson James

Albert Leverson James was a shop manager for his father. When war broke out Albert joined the No-Conscription fellowship. In 1916 Albert attended a Tribunal where he asked to be exempted from conscription due to his pacifist beliefs. He was refused. His orders were to report to Kingston barracks to join the army as a rifleman but he did not report. He was arrested by the police, taken to a Magistrates court and then handed over to the army at Kingston barracks.

By November 1916, Albert was in trouble for refusing to undergo the army medical examination. He faced a court martial. He was sent to Wormwood Scrubs prison, where conditions were poor. Albert fell ill and accepted work on the Home Office Scheme, doing labour for the government, such as working on a farm, in the hope of securing better conditions.

Albert's friend, Frank Lloyd, remembered that 'He was in A Hall at Wormwood and it was evident he was going into consumption. During the last two weeks at A Hall we all suffered terribly from cold and the weather was Arctic. The heating apparatus became out of order. It took me all my time to keep well. It finished Mr. James off'.

Albert was moved to Wakefield and in April his mother and sister were called to visit him. He was by now severely ill, having been kept in an unheated cell and exposed to long periods outside in the snow and rain. Albert died on 7 May 1917.

Albert's death was raised in Parliament as an example of the Government's disregard for men whose only crime was refusal to kill. Albert is commemorated on the Conscientious Objectors' plaque, together with 69 other Conscientious Objectors who died during the war.

'Work of national importance'

Another Conscientious Objector, Felix White, had a different experience:

Felix (born in 1884) was the eldest of five children of a poor family. His mother taught him to play the piano as a child. Felix quickly became renowned and in 1907 one of his works was played at the Proms.

When he was called up in 1916, Felix applied for an exemption at a Tribunal in Kingston. He stated that he was a Conscientious Objector for 'artistic reasons'. He may have had an additional reason-his wife, Martha, was Swiss-German. Perhaps Felix did not want to fight men who could be his relatives?

Like many people of German descent in Britain at the outbreak of war , Martha was afraid of anti- German feeling. She changed her name to the more English sounding, Elizabeth.

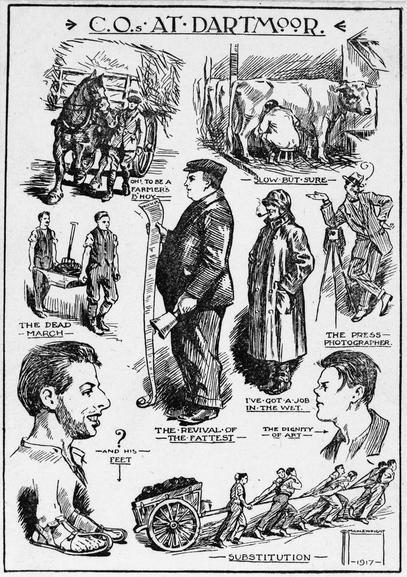

Felix was exempted from serving in the army on the condition he undertook 'Work of National Importance' on the Home Office Scheme. Like many Conscientious Objectors, Felix was not allowed to continue in his own work, or to work near his wife and family.

He spent 2 years as a labourer on farms in Cornwall and Hemel Hempstead. Conscientious Objectors received little pay and lived in very basic conditions.

After the war, Felix composed a piece called 'Fanfare for a Challenge to Accepted Ideas', inspired by his dedication to resisting war and militarism. Today he is remembered for his music rather than his pacifism.

There were over 20,000 Conscientious Objectors in Britain between the years of 1916-1918. The plaque commemorating those who died during the war can be seen at 1 Peace Passage, London, N7 0BT.

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.

2 comments

Comment by Antoin Daltún posted on

Conscription never applied in Ireland (which was then part of the United Kingdom). By 1918 in addressing a very grave military situation it was decided to use a new Military Service Bill to extend conscription to Ireland and also to older men and further groups of workers in Britain, thus reaching untapped reserves of manpower.

On 18 April 1918, the Irish Anti-Conscription Committee was convened to devise plans to resist conscription, and represented different sections of nationalist opinion: John Dillon and Joseph Devlin for the Irish Parliamentary Party, Éamon de Valera and Arthur Griffith for Sinn Féin, William O'Brien and TM Healy for the All-for-Ireland Party and Michael Egan, Thomas Johnson and W X O'Brien representing Labour and the trade unions.

On the evening of the same day, the Roman Catholic bishops were holding their annual meeting and declared the conscription decree an oppressive and unjust law, calling on the Church's adherents to resist "by the most effective means at our disposal" (if "consonant with the law of God.

On 23 April 1918, in a General Strike, work was stopped in railways, docks, factories, mills, theatres, cinemas, trams, public services, shipyards, newspapers, shops, and even Government munitions factories.

The net effect was to unite nationalists and to give Sinn Féin respectability in its campaign for full independence for Ireland.

Comment by Lucy Harris posted on

Thank you for your interesting contribution to this post. It's important to highlight how other countries reacted to Conscription.