The Colonial Office and the Foreign Office have very distinct histories. The British Colonies were initially administered jointly by the Secretary of State for War, and the Board of Trade, who were focused on their own interests, not necessarily the Colonies themselves. From 1795 all the attention was aimed at the war with France, especially under Lord Hobart, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies from 1801. This resulted in the Colonies being neglected. Even Prime Ministers took very little interest in the Colonies. It was not until 1825 that the Colonial Office took prime responsibility for administering the British Colonies. In contrast the Foreign Office, formed in 1782, had always enjoyed a large degree of control over its own affairs.

War and the Colonies

The 1806 appointment of William Windham, as Secretary of State saw him separate the War and Colonial Offices. A new Under Secretary was appointed to oversee the Colonies, with a separate military Under Secretary for war duties. Then followed the first steps towards emancipation and the registering of slaves, and also policy debates on Australia. Parliament now ensured any constitutional decisions regarding the Colonies had to be submitted to the two Houses.

Then in 1816 Lord Tierney suggested the Home Secretary should hold responsibility for the Colonies; or alternatively the Home Office and Board of Trade would divide responsibilities for the Colonies on a geographical basis. Government voted against these suggestions.

The Colonial Secretary's role became unattractive - heavily burdened, with no reward of parliamentary triumphs or promotion.

The end of the war with France saw the Colonial Office remain as a Colonial and not a Military Department and both Lord Bathurst, Private Secretary, and Henry Goulburn, Under Secretary, took personal interest in the Colonies.

In 1825 an Order in Council settled the establishment of a Permanent Under Secretary, Chief Clerk, seventeen clerks, the Counsel, Librarian, and assistant Librarian, a Registrar and his assistant, a précis writer, two office keepers, two porters, a housekeeper and a private secretary to the Secretary of State. The Chief Clerk role was abolished in 1833, leaving approximately 25 permanent officials in post. This number remained relatively the same until 1850.

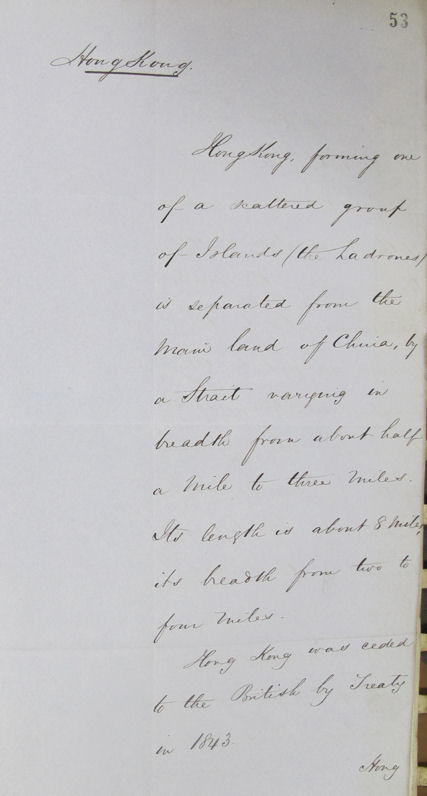

The Colonial Office was made up of five departments, General, North American, West Indian, Australian, African, and Mediterranean. A sixth, the Miscellaneous department, was added in 1843.

By 1827 when Bathurst retired the Colonial Office had a large degree of control over thier own affairs, through finances, appointments and structure. This was possibly more to do with the actions of Henry Goulburn and Wilmot Horton, Private Secretary, rather than Bathurst.

Reform and Reorganisation

The 1848 budget resulted in a reform of the public service. The enquiry resulted in reforms of the public service, including the Colonial Office. A select committee including Sir Trevelyan, Assistant Secretary, Treasury, Gibson Craig, Junior Lord, and Herman Merivale, Permanent Under Secretary, conducted the inquiry of the Colonial Office. The reorganisation of the Colonial Office resulted in Clerks now undertaking an examination, rather than the usual unpaid probationary period. Junior Clerks would previously have received no salary initially, and had to wait for a vacancy before being admitted to the Class of assistant junior clerk.

The general framework within which the Colonial Office operated saw remarkably few changes from 1820 up to the 1960s, when the Colonial and Foreign Offices merged. Colonial affairs have always been debated in Parliament, and colonies would implement laws similar to those in force within the United Kingdom. Very few decisions in a colony could be implemented without agreement from Parliament. So to a certain degree, they were treated as if they were administrative counties of Great Britain.

You can find a timeline of the Government Departments responsible for foreign affairs during the twentieth century on the National Archives Labs website.

Roles and responsibilities within the Colonial Office

From 1833 to 1850 there was no central registry; the Registrar and his assistant had left by 1833, and the Library was mostly neglected. The Librarian spent the majority of his time preparing parliamentary returns. These included the ‘Blue Books’, or annual statistical returns from the Colonies. The Librarian was also responsible for the Legislative Acts, Proceedings and Government Gazettes. Following regulations passed in 1837, the Colonial Governors were instructed to send annual reports to the Colonial Office.

The ancient office of the Chief Clerk was placed under the General Department. The Chief Clerk dealt with the general and establishment questions, accounting, drafting formal instruments and the military business for the Secretary of State for War. Circulars to all Governors, registers of daily correspondence, honours and awards, military matters and maps were all dealt with by the Chief Clerk. The Chief Clerk was also responsible for the library and the Registry. Incoming correspondence was dealt with by the Registry, and this included the ‘Unregistered Correspondence’. These 'Unregistered' despatches and letters covered various subjects, not covered within the scope of the other departments.

Although in most cases only the registers of the 'Unregistered correspondence' survive, they are a great source for researching the overview correspondence regarding the Colonial Office in general. There are also lists of the circulars sent to all Governors and territories.

Honours and Military matters

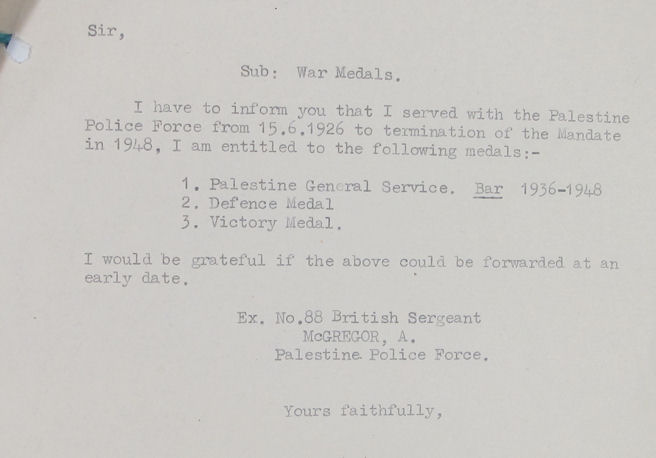

From 1927-1951, the Chief Clerk also dealt with the Colonial military forces, predominately the King's African Rifles and the Royal West African Frontier Force . These include records on the organisation and administration of the forces, but, not the personal information on those who served. The military correspondence also include awards for the Palestine Police force. These records do not include service records either, but they do contain claims for the Defence and Victory medal during the Second World War.

Records of the Honours and Awards include the Imperial Service Order (ISO). But the more interesting series is The Order of St Michael and St George. The awards include details of those awarded honours, short citations, lists of individuals, and in some cases where they were rejected, or postponed.

The Order, established on Corfu in 1818, was to reward those from the Ionian Islands and Malta. From 1864 the honour was expanded to the Colonies. These files include details and images of the refurbishment of the chapel in St Pauls, where the Order resided from 1906.

For those sharp eyed readers, James Bond holds a CMG, Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George, whilst ‘M’ (Dame Judy Dench) was offered the rank of GCMG, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George, if she retired.

Using the Colonial office records can give a better understanding of how the Empire was administered. You can research each Governor's correspondence, as well as the Sessional papers and Acts enforcing the laws within each country or territory. They also help to explain how the empire has changed over the last 250 years, with the change in boundaries, ownership and administration. To gain a better understanding of the records, read Administering the Empire, Mandy Banton (Institute of Historical Research : The National Archives, 2008).

If you are interested in researching Colonial Office records you can find them at The National Archives. For more help understanding these records see the research guide How to look for records of Colonies and dependencies from 1782

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.