Tuesday 20 January marks the 750th anniversary of the beginning of a crucial parliament in the history of government – one that marks an important change in the extent to which people outside the aristocratic classes were involved in politics.

The parliament was instigated by Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, the leader of the baronial rebellion against King Henry III. Simon had defeated Henry III and his forces in battle at Lewes in May 1264, and as a result was in charge of the government – though he was still ruling in the name of the king, who was his captive. But even in these circumstances Simon’s grip on power was far from complete: many powerful nobles were hostile to him, royal officials still controlled many key castles and Henry’s loyal and dynamic queen, Eleanor of Provence, was a few miles across the sea in France.

Summoning the people

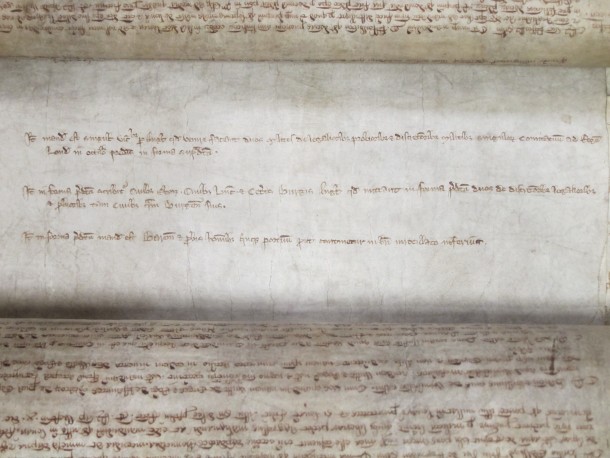

In an attempt to quell the unrest, Simon called a parliament so that he could give the appearance of legitimacy and of governing with the guidance and consensus of representatives from across the realm. This document records the various writs sent out to summon people to that parliament. Because the writs were sent as ‘letters close’ (letters folded up with the Great Seal across their closure), the document on which they were enrolled is called a Close Roll. It is essentially central government’s file copy of the letters that it despatched. This roll, which covers the 49th year of the reign of Henry III (Oct 1264-Oct 1265) is now part of the huge collection of medieval central government documents held at The National Archives, Kew, under the Catalogue reference C 54/82.

The roll shows that writs were addressed to the sheriffs (who were the key royal officials in each county) that they should send ‘two of the more law-worthy, honest and prudent knights from each of the counties’ and to the ‘citizens of York, Lincoln and other boroughs of England that they should send… two of their most prudent, law-worthy and honest fellow citizens or burgesses’. Other summonses were sent to nobles loyal to Simon, to churchmen, and to the Cinque Ports (five Channel ports that had special privileges and responsibilities).

We thus have firm evidence that the 1265 parliament had representatives from both the counties and the towns, who gave counsel to the leaders of the kingdom alongside the nobility and the clergy.

Significance of the parliament

We cannot quite say that this was a ‘first’ – knights had certainly been represented at some parliaments earlier in the 13th century, and it is likely (though the evidence is somewhat limited) that townspeople had too on occasion. But these earlier appearances generally seem to have been because specific issues were being discussed – usually, taxation. The 1265 parliament was different. Taxation was not an issue; rather the knights and the townspeople were there to discuss and advise on some of the major questions facing the realm at the time. So while it may not have been the first time that lay people outside the aristocratic class were present at parliament, it was an important step in extending the role of ordinary people in government. Simon de Montfort’s 1265 parliament deserves to be remembered as a crucial step on the road to modern democracy.

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.