William Wyndham Grenville was born on 24 October 1759 in Buckinghamshire, the youngest son of an earlier Prime Minister, George Grenville, and cousin of a future one, William Pitt.

He studied at Eton, Christ Church Oxford and Lincoln’s Inn, but he abandoned plans for a legal career when he was elected MP for Buckingham in 1782 and then Buckinghamshire in 1784, through the influence of his elder brother George, Earl Temple. He served under his brother as Irish Chief Secretary in Dublin during Shelburne’s ministry of 1782-3, but when Temple was later forced to depart from the government he had formed with Pitt, the Younger, Grenville survived and became Paymaster of the Forces and a member of the Privy Council.

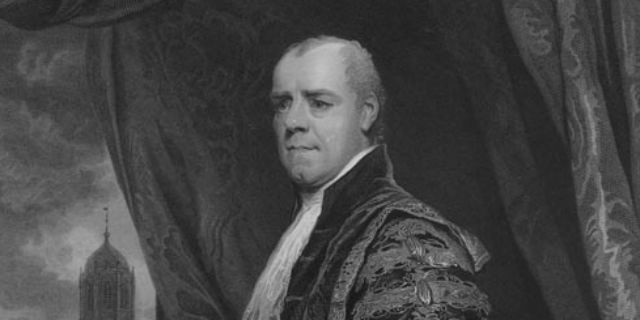

Source: Government Art Collection

Ungainly manner and appearance

Grenville’s intelligence and application were now apparent beyond the ungainly manner and appearance (and questionable dress-sense) that won him the nickname ‘Bogey’. They made him one of Pitt’s closest advisers and a key member of both the Board of Trade and Board of Control, central agencies in Pittite reforms like the creation of the sinking fund, established in 1786 to abolish the national debt. In 1789 he took charge of the Home Office, and the following year was created Baron Grenville to lead for the government in the House of Lords. In 1791, aged only 31, he was appointed Foreign Secretary, an office he held for almost ten years during the long period of international crisis following the French Revolution.

Grenville played a key part in constructing the alliances necessary to sustain the policy of continental engagement and the encouragement of counter-revolution in France, which he preferred to the emphasis on naval power and colonial focus advocated by others in the government. He was beginning to entertain thoughts of a negotiated peace, however, by the time he resigned with Pitt over the King’s refusal to countenance Catholic emancipation in 1801, which he believed essential to the success of the Act of Union with Ireland that year.

The ‘Ministry of All the Talents’

Grenville’s opposition to the 1802 Peace of Amiens negotiated by the Addington ministry saw him become a focus for opposition and work with the Whig leader Charles James Fox, whom he came to regard as a necessary component in any government in which he could serve. Following Pitt’s death in 1806, it was to Grenville that the King turned to form a ministry embracing several political factions - dubbed (satirically) the ‘Ministry of All the Talents’. In a threatening international context, the government struggled to find an effective foreign and military policy, or indeed a domestic policy capable of sustaining the war effort. Its most lasting achievement was the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, in which Grenville, an abolitionist of long-standing, took the parliamentary lead. The government eventually fell in March 1807 when it clashed with George III over its proposal to allow Roman Catholics to serve in the army up to the rank of general, and the monarch demanded a pledge from his ministers not to raise the Catholic question in future.

Leader of the opposition

Out of office, Grenville became leader of a Whig opposition to his former Pittite colleagues, whose stance on the Catholic issue led him now to regard them unequivocally as ‘Tories’. Differences over policy with Foxite allies and the government’s successful prosecution of the war, however, limited his effectiveness, and in 1817 he retired from the role. A stroke in 1823 did not prevent his occasional and effective intervention in political debates before his death on 12 January 1834 on his estate at Dropmore, Buckinghamshire.

Born

25 October 1759, BuckinghamshireDied

12 January 1834, BuckinghamshireDates in office

1806 to 1807Political party

WhigMajor acts

Slave Trade Act 1807: abolished the slave trade in the British Empire.

Copyright Professor Arthur Burns. This article was produced as part of the No10 Guest Historian series, coordinated by History & Policy.

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.