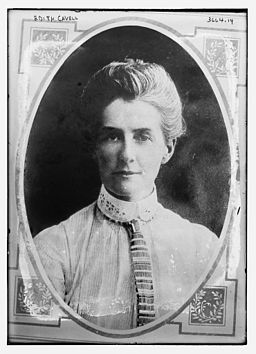

In the early hours of Tuesday, 12 October 1915, Edith Cavell, a British nurse who had been working in Belgium, was executed by the Germans after being found guilty of helping over 200 Allied servicemen escape to England. At her trial she confessed freely to doing this. Many others, mostly Belgian, had been arrested with her, of whom 26 were found guilty and 5 condemned to death, though in only two cases was the sentence carried out. Cavell’s hasty execution, before anyone had time to appeal on her behalf, caused international outrage. She became, literally, a poster girl for both sides in the First World War.

The Germans publicised her fate to discourage resistance and espionage; the Allies publicised it to encourage recruitment and stiffen public resolve against German barbarity. A Foreign Office official, however, suggested that her death, while ‘part and parcel’ of a German ‘policy of frightfulness’, might also be a sign of weakness 1. Cavell’s execution needs to be set in its wartime context to understand its particular resonance.

1915: a year of transition

By the autumn of 1915 it was clear to all warring parties that the war initially expected to last six months was going to go on for a long time. It had become, as historian Sir Michael Howard has written, less a traditional struggle for power than a conflict of ideologies 2.

Overall, the advantage in 1915 seemed to lie with the Central Powers, principally Germany and Austria, though a divided approach to the campaign against Russia weakened their initiative and Austria was close to collapse. For Britain, the disastrous Dardanelles campaign in the spring had served to emphasise the fact that the Balkans were lost to the Allies, despite Italy’s joining the Allied cause in April. By the autumn, both sides were committed to renewed campaigns on the Western Front: the Allies, led by Britain and France, to help their Russian ally, the Central Powers to encourage Russian weakness and strengthen the call for a separate peace.

During 1915 the Allies had discovered they did not have enough of the right kind of guns, ammunition or men to fight the war they were faced with, and their communications were poor. The Central Powers discovered that success would require new defensive tactics, while on the Eastern Front infantry attacks behind a curtain of prolonged artillery fire worked better.

On the Western Front the difficulty for both sides of attack and defence meant that attrition—exhausting the opponent—became an objective. In 1915 the extension of hostilities fostered innovation on both sides, in armaments, in communications, in tactics and in staff work. It also increased the importance of propaganda.

Edith Cavell and the propaganda war

Public perception was important to the prosecution of the war on both sides, to boost recruitment and ensure the continuing support of the belligerent peoples for a conflict with no early end in sight. Each side disseminated or encouraged the publication of material exposing the barbarity of the other. In Britain, popular opinion was whipped up by the press with stories of atrocities, especially after the Germans began to use chlorine gas as a weapon during the spring of 1915.

Anti-German sentiment led the Royal Family to change their Germanic surname to Mountbatten, German Shepherd dogs were rebranded as Alsatians and Wagner’s music outlawed from the concert halls. The Central Powers also put out stories of barbarity, accusing the Allies of colonial aggression and underhand tactics. In particular, the Germans wanted to discourage espionage and resistance in the countries they had overrun, such as Belgium.

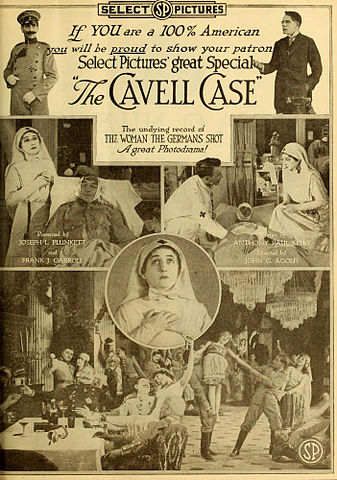

The case of Edith Cavell played into both sides’ propaganda effort. In Britain, she was portrayed as an angel of mercy, persecuted for her efforts to nurse wounded and dying servicemen and for helping them get home. For the Germans, she was a symbol of underground resistance who must be made an example of, to discourage others. Another Englishwoman nursing in Belgium wrote that after Cavell’s arrest posters appeared in the area, warning that ‘Whoever knowingly aids in any manner whatsoever an enemy of Germany in concealing his presence whether by giving him lodging, by clothing him or by giving him food is liable to the same punishment−Death−or penal servitude’ 3.

Cavell’s execution also provided propaganda material in the Allied nations. She featured on the front page of the New York Times, and her image was used widely on recruitment posters and propaganda literature.

Regular army and territorial enlistment rose substantially in late October and November 1915. Certainly there was widespread public revulsion at her fate, particularly at the idea of executing a woman. The speed with which the Germans had acted in carrying out the sentence suggests they expected such reactions; it also shows how important they estimated the deterrent effect of her execution to be.

An unlikely spy?

There have been suggestions that Cavell was involved in espionage, for which her activities on behalf of servicemen were a useful screen. There is no evidence to suggest she was working for any formal intelligence organisation, and she was not charged with espionage by the Germans. But her activities in coordinating the shelter and onward passage of Allied servicemen through Belgium were undoubtedly part of an organised resistance network. Such networks were an important feature of the intelligence landscape of the First World War.

In 1915 both MI1(c), the British overseas intelligence organisation (later called SIS, the Secret Intelligence Service), and British military intelligence were very active in Belgium and France, supported by a large number of civilian networks. For example, the Dame Blanche network of train-watchers in Belgium numbered about 800 people of all ages supplying intelligence on German troop and equipment movements to the Allied military authorities 4.

The image of a young, innocent nurse (though Cavell was 49 when she died), bravely working in secret to protect Allied servicemen was a potent one that was useful to the intelligence authorities as well as the military and political ones.

Patriotism is not enough

There are many memorials in Britain to Edith Cavell, some inscribed with her words: ‘I realise that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone.’ German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann, commenting on Cavell’s fate, added a rider to this: ‘In war one must be prepared to seal one’s patriotism with blood, whether one faces the enemy in battle or otherwise in the interest of one’s cause.’ 5.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.

1 comment

Comment by luchmun sachidhanund posted on

All my respects to this brave lady.ln Mauritius, her name has been to a street in Port Louis.She remains an excellent reference for humanity.