Edward the Confessor, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, died on 5 January 1066 – 950 years ago.

The Confessor’s modern-day reputation (shaped by medieval monks writing after his death) is that of a gentle and peaceable man. Yet his death sparked one of the bloodiest periods in English history, as rival claimants to the crown of England battled it out, and the man who was ultimately successful – William the Conqueror – ruthlessly imposed his rule on his new kingdom.

So why did the reign of the placid and pious Confessor give way to such bloodshed and chaos? And who were the men who were prepared to fight to the death for the right to succeed him?

Anglo-Saxon succession

Framing Edward the Confessor as the last Anglo-Saxon could give the impression that his own succession was easy – the last in a long line of Anglo-Saxon rulers, taking the throne one after another without incident. This is very far from the truth.

Edward was the eldest son of King Aethelred (‘the Unready’) from his second marriage to Emma, the sister of Duke Richard II of Normandy. This marriage had been arranged as part of Aethelred’s attempts to improve English relations with Normandy. But Aethelred had sons from his first marriage, and when he died in 1016, he did so in the midst of a battle for the throne between his eldest surviving son, Edmund Ironside, and Cnut the Great of Denmark. Edmund though died shortly afterwards, and at his death, Cnut succeeded to the kingdom of England.

At Cnut’s death, another succession dispute erupted between the sons of Cnut’s first wife, Aeflgifyu of Northampton, and those of his second wife, Aethelred’s widow, Emma. In that dispute, Edward’s brother, Alfred, was murdered, perhaps at the instigation of Emma. Only after seven long years did Edward eventually succeed to the kingdom of England in 1042, putting the line of Wessex back on the English throne.

Even so, we must not see Edward’s succession as restoring any sort of ‘natural order’ – although his succession does not appear to have been questioned or contested, he was fortunate in that he lacked any obvious rival, and that he had the support of the hugely powerful Earl Godwine of Wessex (of whom, more later). To put it simply, England at this time had very few clearly established principles of royal succession; kinship to the late king, designation as his heir, support from the Church and the nobility (including the men of London), and military might were all factors – but there were no simple constitutional principles that defined who must be the next king.

The Confessor’s kingdom

Nonetheless, in 1042 Edward became king. He was in his late thirties and had spent much of his life in Normandy, living under the protection of the dukes of Normandy while the Danes ruled England. He had no powerbase of his own in England and needed the support of the three great English earls, Godwine, Leofric and Siward – and in particular of the greatest of the three, Godwine. To this end, Edward swiftly gave earldoms to Godwine’s eldest sons, Swein and Harold, and in 1045 he married Godwine’s daughter, Edith. At the beginning of his reign then, Edward’s power was constrained by the power of his wife’s family, who in turn jockeyed for position with each other and with the other great noble families. Edward’s own men – the trusted friends who were dependent on him and could thus be depended upon – were few and far between.

There can be no doubt that it was Earl Godwine’s intention that the marriage of Edward and Edith should produce a boy, his grandson, who would be the next king of England. But there everything did not go according to plan. The marriage of Edward and Edith remained childless. It suited some later religious authors to portray this childlessness as a deliberate policy – a depiction in which the king is pious and unworldly, and in which the marriage is more like a father-daughter relationship. In fact, for much of his reign Edward was an active, dynamic man and there can be little doubt that he intended this marriage to produce an heir. Edith was significantly younger than Edward and may have seen him as something of a father figure – but she would certainly have known that the birth of a child was central to the plans of her actual father, and she knew her role.

As time went on, the couple’s childlessness became a bigger and bigger issue. The Godwine family remained hugely powerful (with the odd hiccup, most notably in 1051-2 when Godwine and his sons were briefly outlawed, and Edith briefly sent to a nunnery). Godwine himself died in 1053 and was succeeded at Earl of Wessex by his eldest surviving son, Harold. Deaths among the other great noble families led to Harold’s brothers establishing themselves in other earldoms, until the sons of Godwine were the provincial lords of much of England.

But Edward maintained good relations with the Norman court, now ruled by Duke William. In addition, in 1054 Edward sent Bishop Ealdred of Worcester to the continent to search for the son of his elder half-brother, Edmund Ironside. This son, Edward (known latterly as Edward the Exile), duly came to England with his Hungarian wife and their three children. The family arrived in 1057 – surely in the hope that this Edward would be designated as King Edward’s heir. But he died shortly after his arrival in England – before even seeing his uncle. However, his wife, Agatha, and the three children were welcomed at the royal court and continued to live there.

The rivals for the throne

At Edward’s death, on 5 January 1066, there were then three strong candidates for the English throne. As we have already seen, succession principles were far from clear cut and each of these candidates had points in their favour:

- Earl Harold, the powerful Earl of Wessex, brother-in-law and friend of the late king. Harold did not have royal blood but he was an adult magnate at the heart of English government and the brother of the widowed queen;

- Duke William of Normandy; the late king’s mother, Emma, was the sister of Duke William’s grandfather, making William and Edward first cousins once removed. So William was a close kinsman of the late king, but he was a foreign duke with no powerbase in England;

- Edgar Aetheling, the young son of Edward the Exile; Aethelred the Unready was the late king’s father and Edgar’s great-grandfather. Edgar was thus the direct inheritor of the English royal line. But he was a child with no significant following and so no immediate prospect of being able to rule independently.

One crucial question is what Edward the Confessor himself intended – although even here we must bear in mind that while the wishes of a king could strongly influence who succeeded him, it was not necessarily the deciding factor. The question of Edward’s intentions has troubled historians for centuries – largely because the partisan English and Norman sources disagree about what happened at certain crucial moments. Thus to a great extent, historians have chosen which sources they agree with, or tried to synthesize the arguments in some way.

There is little evidence to suggest that Edward the Confessor intended at his death to be succeeded by his greatnephew, Edgar Aetheling. The moniker ‘Aetheling’ was an Anglo-Saxon word that denoted that the boy was worthy of the throne, but it did not mean that he was Edward’s intended successor. The Aetheling lived at the royal court for nearly a decade but was granted no significant lands or titles, and did not regularly appear as a witness of his great-uncle’s royal charters, something which we might expect to see if the Confessor was attempting to promote him as a potential successor.

The rival claims of Harold and William – which would of course be ultimately resolved by force at the Battle of Hastings – are harder to unpick. To deal first with Harold, he was without any doubt a hugely powerful figure by the mid-1060s. Edward had attempted to escape from the power of Godwine and his sons in the early 1050s, but having failed so to do, he allowed the balance of power to tip in favour of the family. After Godwine’s death he either facilitated or at least acquiesced in Harold’s establishment as England’s premier earl. It even appears that in the last few years of his reign, Edward was increasingly stepping back from active political life and allowing Harold and his brothers to play an evermore important role in government. But if Edward considered Harold a viable prospect for the succession, then our story becomes more complicated still – for Harold had a powerful brother, Tostig, who was earl of Northumbria, and of course also the king’s brother-in-law. If Harold would be an acceptable successor, then why not Tostig?

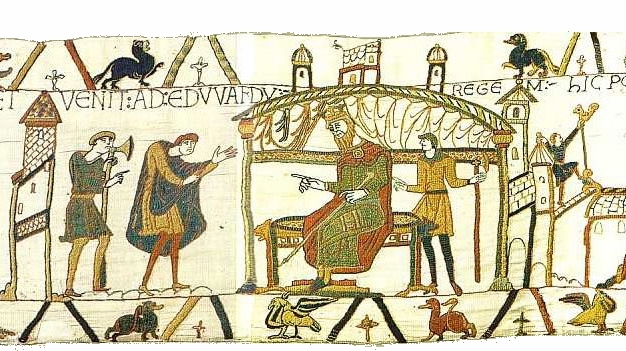

Harold himself may have been keenly aware of this. An event from the final months of Edward’s life is illustrative: in October 1065, there was a violent rebellion against Tostig. Rather than dealing with the incident himself, Edward sent Harold to do so. But Harold failed and Edward was forced to accept the rebels’ demands, exiling Tostig (who fled to the continent) and giving his earldom to Morcar, who was from an old Anglo-Saxon magnate family. This might look like a defeat for Harold but in fact it bolstered it his power by removing one potential rival – his own brother – as well as making the king look weak. Certainly Tostig thought that Harold had conspired with the rebels against him. Some English sources claimed that on his deathbed, King Edward designated Harold as his heir. Other sources are more equivocal; the famous deathbed scene in the Bayeaux Tapestry, for example, shows Edward reaching out and touching Harold, who is kneeling beside him, but the text does not explain the meaning of this gesture. As we have seen, in the early days of 1066 the kingdom was recovering from a crisis and Harold was in pole position – did Edward believe that his succession would be best for the kingdom? We simply cannot say for sure whether the deathbed bequest took place – and even if it did, it does not mean that Harold ‘should’ have been king, or that Edward may not have designated someone else as his heir earlier in his reign.

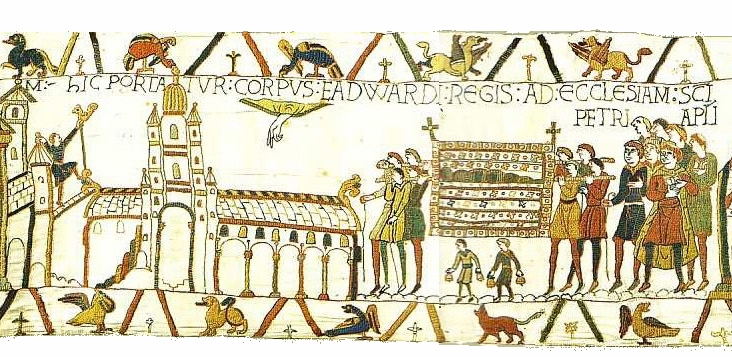

This leads us, of course, to Duke William. William was Edward’s kinsman, and his family had been responsible for protecting Edward during the period of Danish rule in England, and may well have played a supporting role in his establishment as king after Harthacnut’s death. Edward had much to be grateful for. The Norman sources claim that some years before 1066 Edward designated William his heir. Some also assert that Harold himself went to Normandy and took an oath there to support Duke William’s claim. As with Harold’s possible designation, it is impossible to be certain of the truth. Having said that, in the years 1051-2 Edward was seeking to free himself from the control of the Godwines and had sent his wife to a nunnery; it is surely possible that as part of this scheme he looked for an heir unrelated to Earl Godwine. Indeed, it was at this time that the Bishop of Worcester went to continent looking for Edward the Exile. It is thus not a great leap of faith to believe that he may have offered the kingship to William. The idea that Harold swore an oath to William is far more problematic – in the early 1060s, when this is alleged to have taken place, the sons of Godwine were again hugely powerful and it is seems wholly unlikely the Edward could have compelled Harold to make an oath to William, against his own interests. What is more likely is that Harold went to Normandy of his own accord in an attempt to retrieve his brother and nephew, who had been sent there by Edward after the crisis of 1051-2 (this was certainly the later English tradition repeated for us by a monk of Christchurch, Canterbury, who might have been expected to know). While Harold may have been compelled to swear an oath while there (another famous scene in the Bayeux Tapestry), this is very far from the claim that he was sent to do so by Edward and complied of his own free will.

The aftermath of Edward’s death

In the event, might won the day. Harold had himself crowned with a haste that suggests that he knew that his succession was not going to meet with universal approval. William, whether incensed because he thought himself the true heir, or because he was a bellicose buccaneer with a chance of winning a kingdom, began to plan his campaign. At the same time, Harold’s exiled brother, Tostig, began to plan how he could regain his position in England, and formed an alliance with Harold Hardrada, the King of Norway. Thus in September 1066 their joint forces invaded England through Northumbria. On 20 September they met the forces of the English earls Edwin and Morcar in battle at Gate Fulford, near York, and after a long battle defeated them. But by this point the new king, Harold, was on his way and at Stamford Bridge on 25 September his forces crushed the invading armies. Tostig and Harold Hardrada were both killed on the battlefield.

But even as King Harold celebrated his victory, Duke William was preparing to invade at the head of the coalition of northern French forces that he had built. They set sail three days later and on 14 October met and defeated Harold’s armies at Hastings. Harold was killed and William had himself crowned in his stead. It is worth noting that in the aftermath of the Conquest, several prominent English figures wanted Edgar Aetheling to be king, but this was doomed to failure and Edgar eventually fled to Scotland, where his sister Margaret married the king of Scots, Malcolm III. William sought to ‘airbrush’ the reign of Harold from history – in Domesday, the Conqueror’s great record of his new world order, Harold is almost invariably referred to as ‘earl’. The fact that he was briefly king is almost completely expunged from the official record.

History has been kind to Edward the Confessor. The actions of Harold and William have been widely questioned and their rights and wrongs hotly debated. In all of this, we have often been inclined to accept the view of Edward as pious and innocent, at best too unworldly to give thought to the matter of the succession and at worst a gentle man pushed around by his powerful nobility.

But we must remember that it is entirely possible that, affected both by his personal preferences and by the pressure exercised by the powerful people around him, Edward could have preferred different candidates at different times: his marriage to Edith implies an acceptance that a child from this match would be his heir, his recall of Edward the Exile looks like the king thought that he (and perhaps his son Edgar after him) should be his heir, and it certainly seems possible that he promised the kingdom both to Duke William and, later, to Earl Harold. Perhaps then Edward himself should shoulder some of the blame for the bloodshed of 1066.

Further reading:

Frank Barlow, Edward the Confessor (London, 1970).

Stephen Baxter, ‘Edward the Confessor and the Succession Question’ in ed. Richard Mortimer, Edward the Confessor, The Man and the Legend (Stroud, 2009).

George Garnett, Conquered England (Oxford, 2007).

Mark Hagger, William: King and Conqueror (London, 2012)

Richard Huscroft, Ruling England (Harlow, 2005).

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.

1 comment

Comment by David Wilkinson posted on

A further fact relating to the possible designation of Duke William as King Edward the Confessor's preferred successor is that at about the time Earl Harold was supposed to have visited Normandy King Edward's nephew, Walter of Mantes & the Vexim, the son of Edward's full sister Goda or Godifu, had just starved to death, along with his wife, in a Norman dungeon. It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that Harold's mission to the Norman court was in some way connected to this either been a mission to rescue Count Walter and his wife or else to express King Edward's disapproval of the treatment meted out to his close kinsman.

I suspect that this incident may have influenced King Edward's decision to nominate Earl Harold for the throne despite his failure to rescue the King's nephew.