It would not be in the public interest to disclose the circumstances in which Commander Crabb is presumed to have met his death. 1

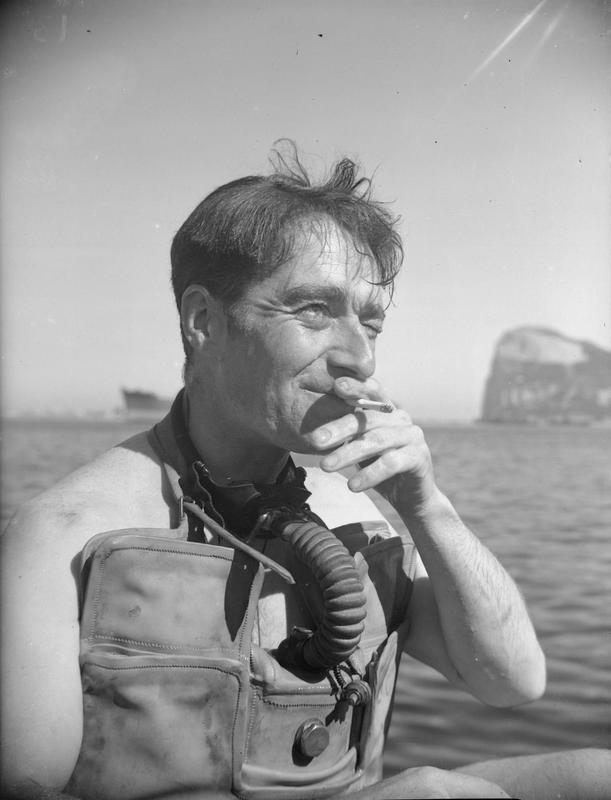

Mystery of the missing frogman

Sixty years ago today, on 9 May 1956 the Prime Minister, Sir Anthony Eden, wrote to Sir Edward Bridges, former Cabinet Secretary, Permanent Secretary to the Treasury and Head of the Home Civil Service, and charged him with carrying out an enquiry into the circumstances in which a retired Naval Commander, Lionel ‘Buster’ Crabb, had on 19 April carried out an intelligence operation against Russian warships in Portsmouth Harbour—a diving mission from which he had not returned.

Eden wanted to know on what authority the operation had been carried out, and why its failure had not been reported to ministers until 4 May. On 9 May the Prime Minister also answered, in three uninformative sentences, a Parliamentary Question that had in fact been put to the First Lord of the Admiralty, refusing all requests for amplification.

Neither the note to Bridges nor the Parliamentary statement reveals fully the fury felt by Eden over this episode. He had specifically forbidden intelligence operations during the visit to the UK of Soviet leaders Bulganin and Khrushchev, respectively Premier and First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It was a goodwill visit, offering the opportunity for productive talks at a time of relative thaw in Anglo-Soviet relations.

But to the UK’s intelligence agencies, it offered a rare opportunity for intelligence procurement. Although Eden had already vetoed the idea of placing microphones in Claridges Hotel (‘I am sorry but we cannot do anything of this kind on this occasion’), 2 an operation mounted by the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), tasked by Naval Intelligence, without the knowledge or approval of ministers, had gone wrong disastrously and very publicly: by 9 May the press were already running a series of sensational stories.

The Bridges Enquiry

The story of Crabb’s ill-fated dive, and the discovery a year later of what appeared to be his mutilated body, is well known. 3 The release in 2015 in the Cabinet Secretary’s Miscellaneous Papers of the full documentation on the Bridges Enquiry 4 provides much detail on a sorry episode that did not reflect well on the intelligence agencies, or on senior officials in the Foreign Office and Admiralty.

It is clear that both Naval Intelligence and SIS thought it a low-risk operation, and that there was no chance of being found out: they had done something similar during a visit of Russian warships in November 1955. They were sure they could carry out the operation secretly and no one would ever be the wiser.

When Crabb failed to surface, the clumsy attempts to cover the operation’s tracks show that those involved still expected the matter to remain secret. In his evidence to the Bridges Enquiry, the head of MI5 (whose role was restricted to that of liaison with the local Chief Constable) observed that the episode showed ‘the chief risk against which one had to plan in mounting clandestine operations in this country was not the enemy or the object of the intelligence, but the British press’. 5

As for informing ministers, the most senior officials in the Admiralty and Foreign Office each said they were waiting for the other to act. Successive witnesses to the Bridges Enquiry spent most of their evidence passing the blame on to others. It is not surprising the Prime Minister was incandescent with rage, and that part of the fallout from the affair was the retirement of ‘C’, Chief of SIS.

The intelligence context

But Eden and his fellow ministers in the Conservative Government in May 1956 had more on their minds than embarrassment (in the press or with the Russians), or the weaknesses revealed by the Crabb episode in the system for authorising intelligence operations. In addition, and not unconnected, they were also faced by other unwelcome intelligence-related developments in early 1956.

On 11 February, the spies Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean surfaced publicly in Moscow, where they had fled five years previously. Then in April 1956, Soviet Military Intelligence announced that it had ‘discovered’ the secret tunnel under Berlin, built by Western intelligence to listen in to Soviet landlines. In fact, plans for the tunnel had been betrayed by SIS officer George Blake to Soviet intelligence even before it was finished.

The breaking of the story in April had some direct relevance to the Crabb story: Patrick Dean, Secretary to the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC), told the Bridges Enquiry that he delayed informing the FO Permanent Under Secretary, Sir Ivone Kirkpatrick, about Crabb’s disappearance because the PUS was at Chequers, discussing the Berlin Tunnel.

Of course, the government did not at that time know that George Blake, then serving in Berlin, was also a Soviet spy; nor that Kim Philby, the former SIS officer interrogated in the autumn of 1955 in connection with the Burgess and Maclean case, was making arrangements in early 1956 to go as a journalist to Beirut, from where he, too, would flee to Moscow. There were quite enough intelligence-related problems for the government to sort out, without considering ones yet to be revealed.

As the detailed evidence and report show, the Bridges Enquiry uncovered slack procedures and poor security, as well as inadequate appreciation of the balance between intelligence collection and the assessment of political risk. The SIS was criticised, FO and Admiralty officials do not come well out of it. The Crabb episode provoked much discussion, including with the JIC, about new procedures for obtaining clearance for intelligence-gathering operations. Bridges himself felt, however, that the results of the enquiry did not provide the kind of reassurance ministers were seeking that nothing like this episode could ever happen again. 6

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.