The Napoleonic Wars in Europe in the early 19th Century saw the Spanish colonies in South America looking towards their own governance and the chance for independence. Joseph Bonaparte was on the throne of Spain, and the deposed Spanish King Ferdinand was held captive. South America did not want a French ruler. This left few options, other than self-governance and ultimately independence. These new juntas or governments required both trade and recognition, as previously trade from the colonies was restricted to Spain. From 1810, and the fight for democracy and self-governance, trade became a tool to bargain for the recognition of the new states independence.

By the end of the conflicts Britain and Spain were allies, having resolved their issues following Napoleon’s control of Spain and the attempt to stop Portugal trading with Britain. This led the Portuguese Court to exile themselves to Brazil; an act that would ultimately lead to Brazil declaring independence in 1822.

Independence

Britain wished to remain on friendly terms with Spain, but also wished for more open trade and commerce markets in the Americas. Britain had for some time announced its intention to recognise the independence of the South American colonies upon the formation of de facto governments with good prospects of stability. In 1823 Britain informed the Spanish Government they were to send Consuls to South America. The requirement for Consuls was a direct result of the increase in British trade and commerce to the Americas. British interests needed protecting, and official representatives were established throughout South America. Without the Consuls, all claims or disagreements would have been required to go through the British representatives in Spain.

Buenos Aires

One of the Consuls sent to South America was Woodbine Parish. He was sent to the port of Buenos Aires. Woodbine Parish was a career civil servant from the age of 14, and, seemingly, a favourite of Lord Castlereagh. Parish had accompanied the expedition to Naples to restore the Bourbon Dynasty; was attached to Castlereagh during the peace settlement following Napoleon’s fall; was an assistant to Castlereagh’s private secretary; assisted Sir Thomas Maitland with the arrangements for the cession of Parga; and accompanied Castlereagh to Aix-le-Chapelle. Following His Majesty King George IV’s visit to Hanover Parish was appointed Commissioner and Consul General to Buenos Aires and arrived in October 1823.

Britain had not made many friends following the attempted invasions of Buenos Aires during 1806-07, but by 1823 the newly formed Province of Rio de la Plata (now Argentina) were looking for support to establish their independence. The opening of trade to foreigners allowed British trade and commerce to flourish. The growing British commerce in Buenos Aires had seen a large British contingent residing in the city, and a need for a representative of the British Government. Woodbine Parish arrived as Consul General in October 1823. His work was mostly resolving issues between British commerce and the new Argentine Government. Though the first year saw Parish settle a new Postal Packet Agreement (Decree of 10 April 1824) resulting in more frequent, and reliable, postal services between Britain and Argentine. This also meant new postal services to Chile, liaising with the new Consul in Santiago, Christopher R Nugent.

Parish concluded the signing of a Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation with Argentina on 2 February 1825. These resulted in a promotion to Charge d’Affaires, and Britain recognizing the independence of Argentina. He was later involved in the end of the Brazilian war and establishment of an independent state of Uruguay.

Chile

Argentina wasn’t the only country Britain sent Consuls to; In October 1823 Christopher Richard Nugent arrived in Chile as Consul General with Vice Consuls Mathew Carter and Henry Rouse. Their port was Valparaiso, the largest and deepest natural harbour on the East of South America. The opening of the Panama Canal, in 1914, saw a decline in the thriving port. The European feel is still evident today in architecture such as the historic quarter of the seaport city, the British Arch and the funicular railways serving the hillside residents and tourist spots.

Chile had already a very European culture. One individual of European descent was Bernardo O’Higgins the illegitimate son of Ambrosio O’Higgins. Ambrosio was born in Sligo, Ireland, moved to Spain, and then proceeded to South America. His move through the Spanish ranks resulted in his promotion to Governor of Chile. During his early years the involvement with a prominent local, Isabel Riquelme, led to the birth of Bernardo. Bernardo was financed by his father, and eventually accepted by the authorities as his son. During his education he spent time in Richmond, Surrey, where a bust is on display by the River Thames.

Following the struggle for independence Bernardo, in 1817, was made Supreme Dictator of the newly independent state of Chile. His role and leadership during the early years is still evident through Chile, with streets, plazas, hospitals, airports and shopping centres named after him.

A British Royal Naval Commander was also involved in the Chilean fight for independence. Lord Cochrane left the Royal Navy following a fraud incident in London. On arriving in South America, Chile recruited him to establish the Chilean Navy.

New Granada

Venezuela had from 1810 attempted diplomatic relations with Great Britain. Simon Bolivar and General Mendez arrived in London in June 1810. They were seeking a promise not to interfere in their independence. They had support from Francisco de Miranda, a staunch advocate for the independence of South America. Before his death in 1801, William Pitt the Younger had agreed to send aid to Venezuela. With no British support Miranda’s attempts to overthrow the Spanish control in Caracas failed.

The war with France now saw Britain supporting Spain against Napoleon. Spain needed the South American finances to pay for their war effort, and pay the allies. So Britain was in the middle, wanting the trade and commerce herself, but also wanting the repayment of loans to Spain, and the defeat of France.

The Mission left empty handed. What Britain did agree was the fate of Venezuela, and the South American states, was in their own hands.

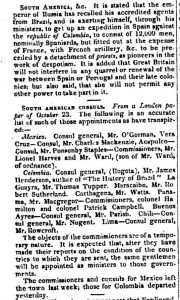

The territory of New Granada also saw the arrival of a British delegation. Colonel J P Hamilton, Lieutenant Colonel Patrick Campbell and James Henderson arrived in October 1823. Their instructions stated “the growing importance of the States of Spanish America and the unsatisfactory nature of the accounts which are derived from accidental sources of intelligence” [FO 18/1]. Spain were unable to regain control of the colonies, France were offering arms to support Spain; and the United States had empowered the President to recognise independence of the former colonies. The special mission of Hamilton, Campbell and Henderson was to establish the actual state of affairs in Columbia. If the Columbian authorities met the criteria set down by Great Britain then James Henderson was to be appointed Consul General. The understanding was for a ‘friendly and commercial intercourse’ with an independent state, not one connected with ‘Spain by subordination’ or ‘any other country by incorporation or federal union’. The instructions also mention that Great Britain could not be induced to bring the state under a British Dominion, or ‘dominion of any other Power’.

Newspaper reports claimed Russia was to send an expedition consisting of Spanish with French artillery at the expense of France.

Admiral Sir Halsted reported an insult against His Majesty’s flag on arriving at Bocca Chica near Cartagena in September 1823. It was not until 23 December 1823 that the matter was settled and the Commissioners proceeded to Bogota.

One issue the Consuls had to negotiate were the Laws decreed by the Government of New Granada. One Law forbid foreign merchants from transacting their own business in the ports of Columbia. By the 21 July 1824 The Consuls reported the regulations had been repealed by Congress.

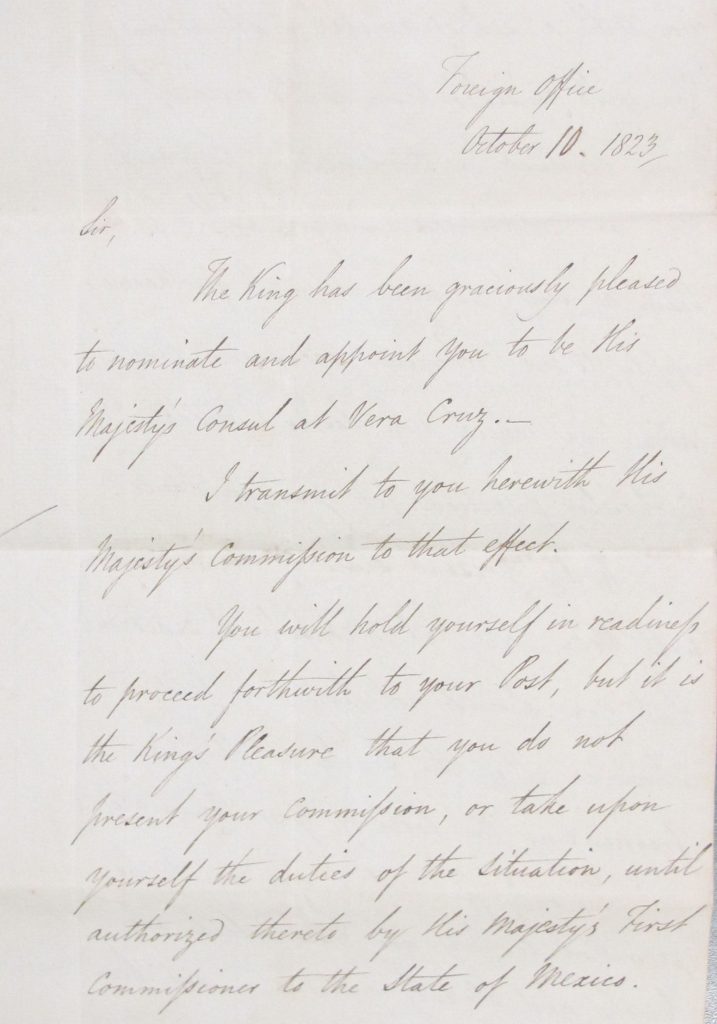

Mexico

In October 1823 Charles O’Gorman was appointed Consul General for Mexico, with instructions to perform his Consular duties for the benefit of His Majesty’s Commercial subjects. This Commission also included Mr Lionel Hervey and Mr Henry George Ward. Hervey and O’Gorman were replaced by a new Commission in January 1825. Mr Henry George Ward, later appointed Charge d’Affaires, and Mr James Morier were appointed to deal directly with Mexican Government. They concluded a Treaty of Commerce and Navigation on the 6 April 1825 and this was eventually ratified in April 1827 by His Majesty’s Government.

The appointment of Consuls resulted in the signing of treaties and agreements with the newly declared independent governments of South America. Spain was now unable to claim back her former colonies. The support of t powers such as Great Britain and the United States meant that the newly formed countries could benefit from trade and commerce. What also resulted from the independence was the outlawing of the trade in slavery south of the Equator, forty years before the American civil war.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.

5 comments

Comment by Ronald Burnett posted on

First class article . Living in Latin America I found it very interesting .

Comment by Melissa posted on

Check spelling of Bernardo under the image. 'r' is missing.

Cheers

Comment by Mark Dunton posted on

Duly corrected - thanks Melissa

Comment by Walter posted on

Hi, good job!

There is an inaccuracy regarding the independence of Brazil: the correct year is 1822. The UK recognized the independence in 1825.

Best regards.

Comment by Keith Mitchell posted on

Walter, Thank you, you are correct. It should be September 1822, following the Cortes action to rebuke Brazil's status as a Kingdom, and annul all Acts passed by the Brazilian Cabinet.