Researcher in Residence: Progress Report II

My name is Jack Brown and I am the first ‘Researcher in Residence’ at No. 10 Downing Street, based at the Policy Institute at King’s, King’s College London. As part of my role this year, I am investigating the ‘Geography of Power’ at the heart of British Government, and the important two-way relationship between No. 10 as a building and those that work and live within it.

This is the second in a series of four blog posts focusing on the rebuilding of No. 10 during Harold Macmillan’s premiership. The first blog provides the historical background to the period. This entry details the rethinking of No.10, with the forthcoming third and fourth parts investigating the Prime Minister’s repeated attempts to intervene and change No. 10 significantly, and the difficult rebuilding works that followed. This series is part of the research for an upcoming book on the ‘Geography of Power at No. 10 Downing Street’, to be published in 2017.

Background

The rebuilding of No. 10 Downing Street, sanctioned in June 1958 and beginning in August 1960, represented a pivotal moment in the building’s history. Centuries old, the decaying houses at Downing Street had not been designed for their purpose, and had been incrementally sustained through regular and costly repairs over the years. By the 1950s, the condition of the houses had become critical. Serious redevelopment had now become essential, and a unique opportunity was presented to rethink the building that houses the centre of British Government. This blog investigates the decisions taken during this process, which would affect the conduct of central government for decades to come.

Harold Macmillan Arrives at No.10

Harold Macmillan arrived at No. 10 Downing Street on 10th January 1957 determined to introduce an air of calm into the building. No.10 had become a fractured place under Macmillan’s predecessor, Anthony Eden, even before the trauma of the 1956 Suez crisis.[i] Events in Suez increased the temperature in the house significantly. Lady Eden, who thought Downing Street ‘the nicest house you could possibly wish to live in’, also famously claimed during the crisis that she had ‘felt as if the Suez Canal was flowing through my drawing room.’[ii] Eden’s subsequent decline served as a stark warning to his successor.

Harold Macmillan’s contrasting approach was captured by a sign he hung on the Cabinet Room door, which bore a quotation from Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Gondoliers: ‘Quiet, calm deliberation disentangles any knot.’ Calm, and a much-reported family atmosphere, would develop as key features of the new Prime Minister’s No. 10; Macmillan’s ban on his grandchildren riding tricycles and bicycles in the front hall on Cabinet days captured both of these elements.[iii] Macmillan warmed to the house, recording in his diary that No. 10 ‘has great character and charm. It is very liveable…’[iv]

Despite this, at the time of Macmillan’s arrival, the deteriorating condition of Nos. 10, 11 and 12 Downing Street was becoming critical. It was becoming impossible to postpone serious renovation works any longer. However, Macmillan was conscious that the general public could react negatively to a Prime Minister apparently electing to spend a large sum of public money on his own house. He told the Ministry of Works in June 1957:

As the present tenant of this great house and as an interested party, I find myself in some difficulty in trying to decide what is best to do. (…) We are all interested parties and before we decide to spend £1 million of public money upon reconstructing Downing Street I am sure that we must fortify ourselves with some independent advice.[v]

Macmillan announced the appointment of a small independent committee, chaired by the Earl of Crawford, in July 1957. The Committee met five times between July and November 1957, and was tasked with considering and interrogating the Ministry of Works’ 1955 report into the state of Downing Street, making their own enquiries, and recommending a course of action to the Prime Minister. Their final report was published in June 1958.[vi]

The Crawford Committee

The Crawford Committee found that the condition of the Downing Street houses had deteriorated even since the Ministry of Works had conducted its surveys in 1954/5. The house was now a severe fire risk, and representatives of the Ministry of Works told the Committee that there was now ‘serious risk of collapse of parts of the building (…) possibly not for twenty years, possibly at any moment’.[vii]

The floor of the Cabinet Room was a particular concern. Strutting underneath the floor, initially installed to provide air raid protection for the Garden Rooms below, used by Churchill during the war, had been retained ‘lest the floor of the Cabinet Room collapse.’ The State Rooms on the first floor, where prominent guests were received and high-profile events were held, required careful management during events; members of the Downing Street staff were circulated to ensure that too many guests did not congregate in any one room, in case they caused a collapse of the floor or supporting walls. The possibility of the full Cabinet falling through the floor mid-meeting, or a group of international dignitaries being entertained upstairs suffering a similar fate, made an upgrade of No. 10 a priority.[viii]

The Crawford Committee concurred with the Ministry of Works’ findings and suggestions, and also concluded that a substantial rebuild of Downing Street was now required. However, the Committee decided that the construction of an entirely new building should be rejected, despite the potential benefits of knocking the existing houses down and starting from scratch. Its final report stated that:

A completely new building would have many advantages, notably that the layout and services could be specifically designed to suit the purposes for which the houses are used. (…) However, we do not recommend this course. The houses, and especially No. 10, have many historical associations and we should deplore their demolition.[ix]

The Committee decided that it was vital to preserve ‘something that has figured so prominently in public life over nearly three centuries and which has become such a familiar feature of the London scene’, and noted that, despite the ‘patchwork’ nature of the building, Downing Street still contained ‘features of great architectural importance’ that they recommended be preserved.[x]

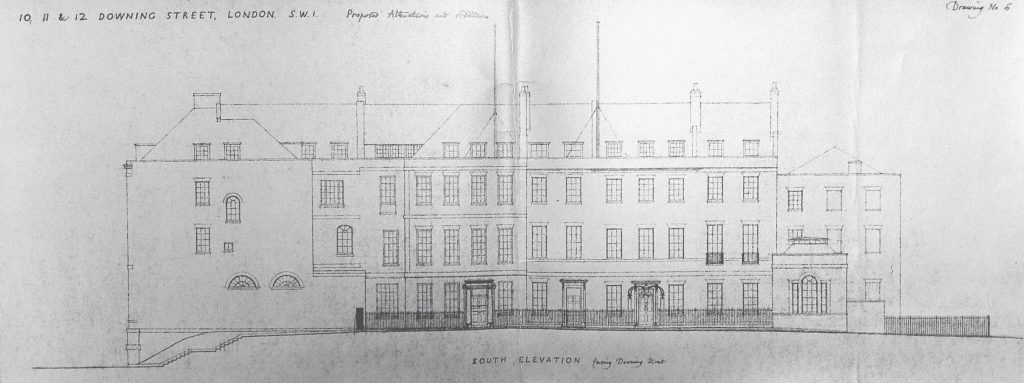

It was recommended that the Downing Street houses should undergo underpinning and grouting to make them structurally sound, but that ‘rooms and features of historic or architectural importance should be preserved.’ This included the Cabinet Room and the suite of rooms around it, historically the offices of the Prime Minister and his or her Private Secretaries, which represented the nerve-centre of No. 10. The State Rooms on the first floor, which had once been the private quarters of the Prime Minister and their family but were now primarily used for ceremonial purposes, should also be preserved. The majority of the houses’ external features should be retained, although No. 12 could be rebuilt to its original height, having been damaged by fire in 1879, and some alterations could be made to the upper floors of No. 10. The Royal Fine Arts Commission were to be consulted on any changes to No. 10’s external appearance.[xi]

The View from No. 10

Ultimately, the Crawford Committee’s recommendations endorsed the Ministry of Works’ original plans, and recommended that an independent architect be appointed to lead the work. Meeting only five times, including one visit to Downing Street on 15th August 1957, the Committee essentially offered an independent check on plans already prepared by the Ministry of Works. Importantly, however, the Prime Minister’s Private Office had also been consulted about these plans throughout their development.

A 1956 note from David Pitblado, then Principal Private Secretary to Anthony Eden, provides an excellent insider’s perspective on the challenges faced in reconstructing Downing Street, and the needs of the Prime Minister’s Office. The note observed that the Prime Minister’s Office is ‘both a Private Office and a small Department.’ Whilst a normal Private Office could rely upon its department for records and services, in this case most such work had to be performed within No. 10. In a sense, the work of the Prime Minister’s office was ‘wider in scope and greater in amount than a normal Minister’s Private Office.’ In addition, the office had been operating 24-hour basis since the Second World War. [xii]

Despite this heavy workload, the relatively very small team that supported the Prime Minister in his or her various functions had changed little in size or structure for several years, and Pitblado predicted that it was ‘unlikely to be modified fundamentally’ in the future. Whilst it was acknowledged that special advisers had been brought into No.10 ‘from time to time’, and that at present there was little room to accommodate such additions, the current structure was ‘certainly the necessary basis of any plans prepared now for the future.’[xiii]

The arrangement of the rooms around the Cabinet Room, which Prime Ministers had generally used as their office in recent years, kept the small team of Private Secretaries very close together, and close to the Prime Minister. The layout of these rooms also provided a waiting room for the Prime Minister’s guests, an ante-room for Cabinet Ministers to congregate before meetings, and easy access to the stairs down to the ‘Garden Rooms’, where confidential filing, typing and other administrative support was housed. Cautious not to lose an arrangement that they felt essentially worked, and with the Cabinet Room suite thought of particular historical value, it was proposed that this layout should be retained. Any capacity for future expansion, special advisers, or re-housing the No. 10 staff currently housed in the adjacent Old Treasury buildings, would have to be found elsewhere, further away from the ‘core’ of No. 10.[xiv]

Pitblado’s note acknowledged that the current arrangements at No. 10’s ‘operational centre’ around the Cabinet Room were flawed, but warned against attempting to alter them. In his view, this part of No. 10 was ‘indeed on analysis surprisingly convenient – whatever other defects it may have – since the rooms were certainly not designed as office rooms.’[xv] However, much of the rest of No. 10 was far less convenient:

The Official staff in No. 10, apart from the Private Office, is housed in accommodation not originally designed for office work. Indeed some of it would be considered quite unsuitable on ordinary standards. But it works adequately and people are reasonably content. Any improvements that can be made on rebuilding would obviously be desirable.[xvi]

It is worth noting that the Cabinet Room itself was not originally designed for its purpose, being referred to in 18th century floorplans as ‘My Lord’s Study’, with the adjacent rooms that now housed the Private Office designated as Waiting and Dining Rooms. It had been knocked through and extended in 1783, with the old wall replaced by the two columns that still decorate the room today. However, despite arriving at the present arrangement essentially by chance, there was little appetite for radically rethinking No. 10’s core layout to suit the changing needs of the premiership. This decision was reflected in both the choice of architect, and the brief given to him.

The Architect’s View

Raymond Erith, a rare but prominent classical architect in a prevailing modernist climate, was chosen to lead the works on Downing Street. Erith saw his role as primarily to renovate and preserve the building’s history, rather than to put his own imprint on it. Erith’s persona is captured in correspondence held in his personal archives at the Royal Institute of British Architects. In late 1958, the Architect’s Journal chose Erith as their ‘Man of the Year’, and contacted the architect for a quotation and profile for their announcement. Erith responded that ‘you could not have picked on anyone about whom there is less to say’, adding that ‘certainly I have built practically nothing that is of architectural interest.’ On the Downing Street job, Erith claimed that, ‘I owe that to Fortune and am very conscious of being in Fortune’s debt: it is still a long way from being an achievement.’[xvii]

Erith’s approach to his work on Downing Street was equally unassuming. The architect stated before the works that ‘I do not intend to leave my mark on the additions in Downing Street, nor on No. 12: I attach no importance at all to originality or modernity.’ Erith’s main objectives were, in his own words, ‘improving vertical and horizontal communications, letting in light, and generally tidying up the mess left by a hundred years of piecemeal additions.’ However, some provision for the expansion of the Prime Minister’s staff was also included. New office space was provided for on the second and third floors, once the decision was made to ‘push the Chancellor as much as possible into No. 12 in order to make room for the expansion of No. 10.’[xviii]

Whilst this new office space was not near to the Cabinet Room, and therefore the Prime Minister, Erith viewed this as a positive. After speaking to the current occupants of No. 10, the architect was reinforced in his view that discouraging the expansion of the Prime Minister’s Private Office, which thrived on being a small and intimate team, was a positive thing: ‘If the Private Office got bigger it would not be possible for everyone to know what everyone else is doing, and soon the Prime Minister would not know what he was doing either.’ Erith noted that he was unsure who would actually use the new space: ‘Advisers? People more or less apart from the Private Office.’[xix] Those assigned rooms in the newly converted offices were therefore consigned to work without the benefit of proximity to the centre of activity in No. 10, although this was still preferable to being housed elsewhere in Whitehall, as had previously been the only option.

Additionally, after investigating and speaking to the staff of the Garden Rooms in the basement, Erith decided that there could be no better location for them, despite their sometimes-dingy location. Instead, work was undertaken to enlarge the rooms and let more light in. The rooms provided quick and easy access to the ‘core’ of No. 10, and Erith found the clerks and typists who occupied the Garden Rooms ‘devoted’ to their location by the garden. ‘They told me, with feeling, that it would break their hearts if they had to go. My sympathies are entirely with them: there are not many offices in London where one can look through an unobstructed window into a garden, and the Prime Minister’s garden at that, nor many rooms with more history: nor are there any other rooms at all that are under the Cabinet Room.’[xx]

It was not uncommon for Erith to be told, when speaking to the current staff of No. 10 about his work, that the existing occupants liked their accommodation very much, but that they would not want ‘to stand in the way of the general good by sticking to this room’. Erith clearly found this slightly frustrating, and eventually elected to ‘put everyone back where he was before in room he is used to and likes, and hope I will be forgiven for lack of puritanical zeal in seeing that everyone suffers for everyones’ well being.’[xxi]

Conclusions

The architect, the membership of the Crawford Committee, and the staff of the Private Office past and present all agreed that the ‘operational centre’ of No.10 should not be significantly altered. Many acknowledged that, should the building be started from scratch, the labyrinth of rooms and corridors would not be designed as they were. Despite this, it was ultimately thought that, as previous Prime Ministers had managed to operate successfully within the existing arrangement, the core layout of No. 10 wasn’t broken, and therefore did not require serious fixing. The upper floors of No. 10 saw more change, and were expanded, with additional office space incorporated, following a gradual trend of upwards and outwards expansion of the working part of the building that can be traced back centuries. However, the Prime Minister, relocated to Admiralty House while No. 10 was under reconstruction, was soon to intervene.

Part Two of Four

This series of blogs are part of a wider research project on the postwar ‘Geography of Power’ at No.10 Downing Street, to be published in 2017.

[i] D. Kavanagh & A. Seldon, The Powers Behind the Prime Minister: The Hidden Influence of Number Ten (HarperCollins Kindle Edition, 2013)

[ii] C. Jones, No.10 Downing Street: The Story of a House (London: BBC, 1985), pp.143 & 153

[iii] A. Horne, Macmillan 1957-1986: Volume II of the Official Biography (London: Macmillan, 1989), p.164

[iv] Ibid., p.14

[v] Prime Minister to Minister of Works, ‘Reconstruction of Downing Street’, 19/6/57, National Archives (TNA), WORK 15/579

[vi] Committee on the Preservation of Downing Street, Report of the Committee on the Preservation of Downing Street (London: HMSO, June 1958)

[vii] Committee on the Preservation of Downing Street, Minutes of First Meeting, 22/7/57, TNA, WORK 15/579

[viii] Jones, No.10 Downing Street, p.178, and; Committee on the Preservation of Downing Street, Report, pp.4-6

[ix] Ibid., p.7

[x] Ibid., p.7

[xi] Ibid., p.10

[xii] D. Pitblado to F. J. Root, ’10, 11 & 12 Downing Street’, 31/1/56, RIBA Archives, ErR/100/4

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] R. Erith to C. Boyne, Untitled Note, 27/11/58, RIBA, ErR/101/2

[xviii] ‘Report on the design for the reconstruction of Nos. 10, 11 & 12 Downing Street’, 30/9/58, RIBA, ErR/100/1

[xix] R. Erith, Handwritten note entitled ‘Downing Street’, 12/6/61, RIBA, ErR/100/1

[xx] ‘Report on the design for the reconstruction of Nos. 10, 11 & 12 Downing Street’

[xxi] R. Erith, Handwritten note entitled ‘Downing Street’

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.

1 comment

Comment by David Matthew posted on

I am surprised that there is no reference to the Treasury Historical Memorandum written many decades ago and of course the Treasury files.

National Archives is known as The National Archives or TNA.