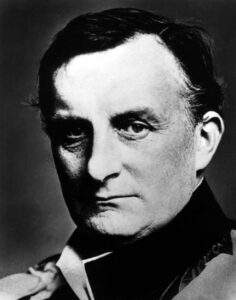

Eleven years to the day Grey was back at the Palace to relinquish his office and again he was shrouded in fog—but this time, the fog of war. A century on from Grey’s resignation we take a look at his final years in office.

The First World War started with something of a paradox for Grey. In the House of Commons on 3 August 1914 he made what is widely regarded as the best speech of his career setting out the case for going to war. But it was a pyrrhic victory as the war proved to be a personal catastrophe.

It is hard not to agree with Grey’s biographer, Keith Robbins, that the gravest handicap Grey had during the war was his own attitude towards it. He was no Churchill who viewed it as a great adventure. ‘Nothing matters now except this awful war’ Grey wrote. ‘None of the things that made life pleasant seem to exist anymore.’[1]

Mental strain

From the outset, the war was constantly on Grey’s mind. He lay awake at night asking himself whether he could have done anything different to prevent it. The sinking of the Lusitania crept into his thoughts as he tried to enjoy the theatre. Kitchener thought him an odd fellow who felt all sorts of things that did not concern him.

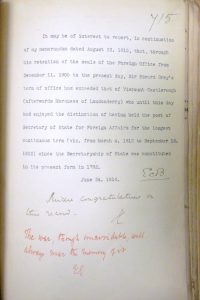

The war entered his dreams. Grey woke on Christmas Eve 1914 thinking that the Germans had landed and come for him until he realised Christmas hymns were being sung outside. Disenchantment surrounded him. When on 24 June 1916 Grey became the longest continuously serving Foreign Secretary he dismissed congratulations with the minute: ‘The war, though unavoidable, will always mar the memory of it.’

Grey was a sensitive man with a great interest in the natural world. He felt keenly the horror of the conflict. ‘The accumulated misery of war makes me feel numb’, he wrote ‘as if my soul has gone elsewhere’.[2]

Wartime work

During the war the Foreign Office expanded into new areas of work, the biggest relating to the economic blockade of Germany. This developed in February 1916 into the Ministry of Blockade, nominally under the control of the Foreign Office, through its Minister, Lord Robert Cecil, who was also the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs.

This was partly a response to the fact that Grey felt both over-worked and lacked the energy or desire to deal with these aspects of wartime work. Despite being a member of the select Council of War set up by Prime Minister Asquith, Grey deliberately took a backseat on questions of strategy believing it was not his place to tell generals what to do.

Physical strain

When the war came it was coupled with the discovery that Grey’s eyesight was deteriorating. He was told to restrict his reading and live a healthy lifestyle. But he could not apply this remedy until he left office, and as months turned into years his frustration grew at being trapped both in the job and in London.

Grey complained of being ‘inhumanly busy’ and often dozed at work. He tried to take regular breaks where his work was covered by other ministerial colleagues. In turn he asked for arrangements to be put in place for Foreign Office staff to take adequate leave adding it was essential to enable workers, however gallant and ready to sacrifice themselves, to get through without a breakdown.

A breakdown is what some suspected Grey was heading for. Asquith is recorded saying in December 1915: ‘His pessimism and nerves are dreadful! I think he is off his head… It’s a curious thing, but Grey had developed lately all the defects I thought he could never have! I hardly value his judgement at all now! He is so unstrung and self-enfolded’.[3]

He was held in post longer than his nerves and health could cope with it. Much of the blame here must rest with Asquith who clearly saw the strain his colleague was under but considered Grey a necessary crutch for propping up the Coalition government.

Out of office

Grey’s resignation came with the fall of the Asquith government at the end of 1916. He said he felt like a man who had walked 1000 miles without rest and had at last been told he could lie down.

The new Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour, offered to send him papers of interest but Grey desired to know no more than the newspapers told him: knowledge was just a cause of useless worry.

Grey had started the war with a sense of duty to the country and the Liberal Party, ‘to see the job through’ but, of course, had no idea how long the war would last and, in the end, even duty was not enough to sustain him.

[1] Grey to Louise Creighton, 9 August 1914, MS Eng.lett.e.73, Bodleian Library.

[2] Grey to Pamela Tennant, 7 April 1918, GD510/1/60/2/33, Tennant MSS, Scottish Record Office.

[3] M. & E. Brock (eds.), Margot Asquith’s Great War Diary, 1914-16 (Oxford; OUP, 2014), p. 221.

- if you are interested in our work then feel free to read our blogs on GOV.UK.

- keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts

- follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians

4 comments

Comment by Robin S. Taylor posted on

"physical stain" should surely read "Physical strain".

Comment by Mark Dunton posted on

Thank you Robin! This has been corrected

Comment by Rob B posted on

Thank you for this pen picture of Sir Edward Grey. Perhaps I can add by quoting two passages from his book Fly Fishing:

Sometimes I think that sea trout fishing is the best of all sport. It combines all the wildness of salmon fishing, with the independence of trout fishing, and one may have all the excitement of hooking large fish without using a heavy rod and heavy tackle. There is less rule and less formality about it than there is about salmon fishing, and there seems more scope for the individuality of the angler. Perhaps this is partly because the sea trout season comes so directly after a long period of work in the stale air of cities, and coincides with the first burst into freedom and fresh atmosphere. The difference is so great in August, after a few days of exercise in the air of the North, that there come times when the angler, who wanders alone after sea trout down glens and over moors, has a sense of physical energy and strength beyond all his experience in ordinary life. Often after walking a mile or two on the way to the river, at a brisk pace, there comes upon one a feeling of "fitness," of being made of nothing but health and strength so perfect, that life need have no other end but to enjoy them. It is as though till that moment one had breathed with only a part of one's lungs, and as though now for the first time the whole lungs were filling with air. The pure act of breathing at such times seems glorious. People talk of being a child of nature, and moments such as these are the times when it is possible to feel so; to know the full joy of animal life - to desire nothing beyond. There are times when I have stood still for joy of it all, on my way through the wild freedom of a Highland moor, and felt the wind, and looked upon the mountains and water and light and sky, till I felt conscious only of the strength of a mighty current of life, which swept away all consciousness of self, and made me a part of all that I beheld.

*

Catastrophes occurred, and by slow degrees and painful losses I learnt the necessity of getting keenness under control. After I had improved in these matters there still remained the hardest trial of all, which has to be undergone by all anglers, namely, how to face the disappointment of losing a fish. Many of us must have known what it is in boyhood to suffer anguish after losing an unexpectedly large fish. The whole of life then seems laid waste by despair; the memory of past joys counts for nothing; one is sure that no future success can ever compensate for the present loss; and one rails against the established order of everything, and is indignant that any human being should ever have been born to undergo such intolerable misery.

And, I am reminded, it was Edward Grey who famously said:

The lamps are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.

Comment by Tom Hughes posted on

I have read other accounts firmly laying a large chunk of the blame for the start of the conflict at his doorstep..... which might explain his later "guilt-trip /breakdown". Not sure if it was an inability to cope with the pre-war crisis, or a premeditated desire for war, either acting as an individual, or part of a group more dedicated to countering German expansionism than anything else.