It is a century since David Lloyd George formed the first ever prime-ministerial policy team, known as the ‘Garden Suburb’.

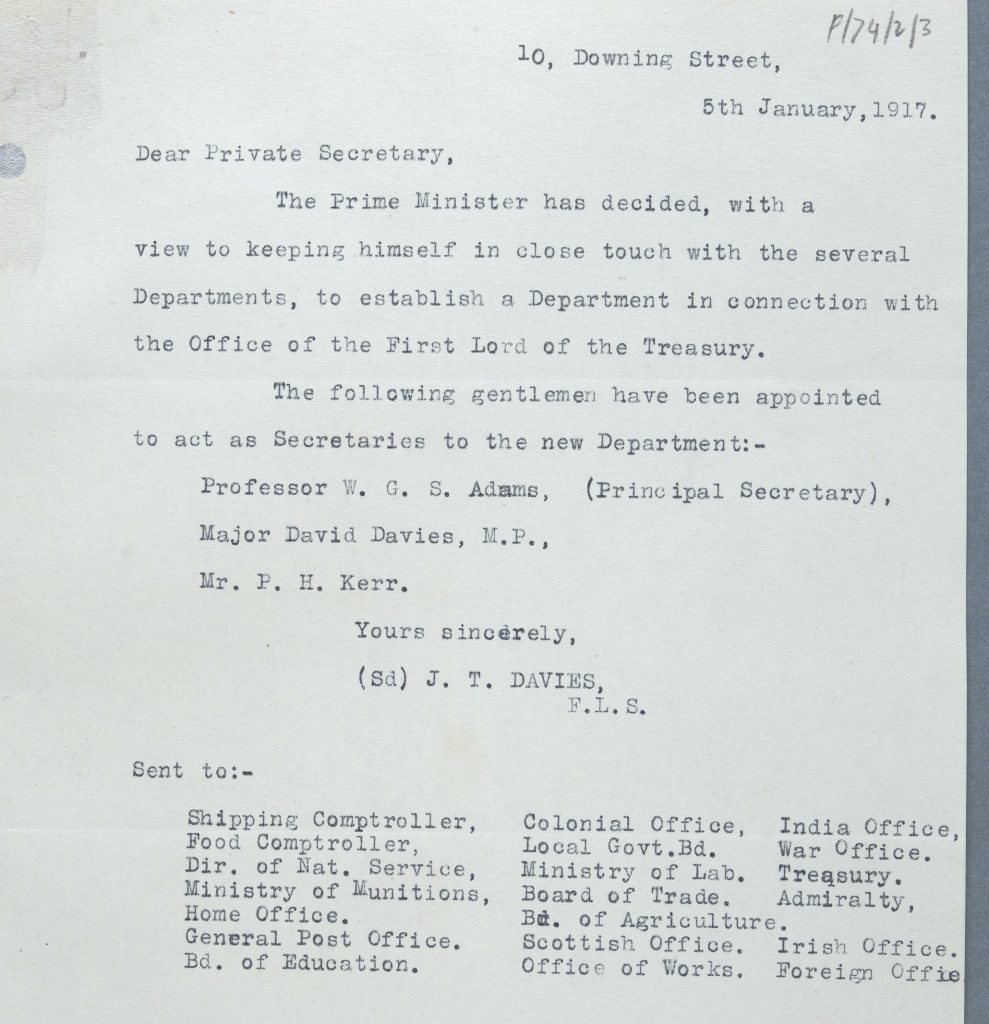

A hundred years ago today, on 5 January 1917, in the midst of the Great War, an important note was circulated around Whitehall departments. J. T. Davis, private secretary to the newly-installed Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, served notice that:

‘The Prime Minister has decided, with a view to keeping himself in close touch with the several Departments, to establish a Department in connection with the office of the First Lord of the Treasury.’[1]

The ‘Garden Suburb’

Lloyd George had formed a small team of staff that would be officially labelled the ‘Prime Minister’s Secretariat’. It became known more widely as the ‘Garden Suburb’, a nickname it gained because it was housed in temporary huts on the lawn of Downing Street.

The Garden Suburb represented a significant augmentation in the support available to the Prime Minister. Before this point, the only full-time official staff available at No.10 was a group of around four private secretaries working in the Private Office at the back of the No.10 building.

Now, in the form of the Garden Suburb, Lloyd George had extra assistance. His successful bid for the premiership in December 1916 had been founded on the idea that he could pursue the war more effectively than had his Liberal colleague and immediate predecessor at No.10 Herbert Asquith.

Central to the new approach Lloyd George sought to take was an overhaul at the centre of government. Forming a slimmed down War Cabinet he attached to it a team charged with supporting and minuting its meetings, and communicating its conclusions around the departments. This entity would develop into the Cabinet Office of today.

Specific support for the PM

Lloyd George formed the Garden Suburb alongside this innovation. Unlike the embryonic Cabinet Office, it supported him specifically, rather than the War Cabinet as whole. The avowed purpose of the Garden Suburb, as the note of 5 January suggested, was to enable him to keep abreast of the work in the various branches of government, enabling him more fully to fulfil the role of dynamic war leader that he envisaged for himself.

Members of the team were each given particular spheres of interest and groups of departments to oversee on behalf of Lloyd George – though they also became drawn into other activities such as political fixing and media management. The head of the Garden Suburb was W. G. S. Adams, an Oxford political scientist who would later be instrumental in the establishment of its Philosophy, Politics and Economics degree. He wrote to Lloyd George on 26 January describing his vision of the Garden Suburb and stressing the importance of achieving wide coverage of Whitehall:

‘It is necessary that there should be a clear arrangement by which there is an Officer who is in immediate touch with each Department of State, and one of the first matters for consideration is to secure that the whole Public Service is provided for in our scheme.’[2]

Formalising the ‘Garden Suburb’

It seems to have been on the insistence of Adams that the Garden Suburb was initially described as a ‘Department’. A draft of the 5 January note announcing the formation of the body within Whitehall, from 2 January, referred to a ‘Secretariat’. This word is crossed out and substituted by ‘Department’, apparently by Adams.[3] But ultimately, the label ‘Department’ was dropped and the Garden Suburb was formally known as the "Prime Minister’s Secretariat". Despite its cross-governmental brief the size of the staff never exceeded six.

![Extract of the draft note from 2 January 1917 on 10 Downing Street headed paper which reads 'To: The Private Secretary, the Prime Minister has decided, with a view to keeping himself in close touch with the several departments, to establish a ['Secretariat' is crossed out and replaced by 'Department'] in connection with Office of the First Lord of the Treasury. The following gentlemen have been appointed to act as secretaries to the ['First Lord of the Treasury' is crossed out and replaced by 'new Department']](https://history.blog.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/01/edited-e1483652073427.jpg)

Impact upon policy?

Collectively the Garden Suburb has attracted attention out of proportion to its size, both from contemporaries and historians. Adams had an important role in Irish policy in the early years. Kerr was influential upon the formation of war aims and drafted part of the fateful ‘war guilt clause’ of the Versailles Treaty of 1919. Yet an enormous impact upon policy for the Garden Suburb generally is difficult to detect.

Overall the Garden Suburb seems to have proved useful to Lloyd George in helping him ensure that sensitive intersections between policy and politics were carefully handled. He was the head of a coalition within which he did not lead the largest party, and the security of his position was always a substantial concern.

In a note drafted in March 1918 Adams provided an assessment of the performance of the Garden Suburb. He described how team members maintained ‘free and informal’ relationships with their allotted departments, the purpose of which was:

‘to help the departments in getting matters to the attention of the Prime Minister when they were of urgency, and, as far as possible to arrange and prevent matters from pressing upon the Prime Minister.’

Adams judged that:

‘it has…been found possible to do a great deal in the way of securing settlement on points upon which there was doubt, if not dispute, and of helping to bring people and bodies together who would benefit by closer relationship with one another in their work.’[4]

In this account Adams espoused the idea of attaching a relatively small body to the office of Prime Minister that could both alert premiers to important developments and alleviate the burden upon them; and that could promote a better-coordinated government. This concept survived in various forms over the next hundred years. It remains relevant in government today.

In the second part of this blog we will consider the legacy of the Garden Suburb and the advisory bodies at No.10 to which it was a precursor.

This post was authored by Dr. Andrew Blick and Prof. George Jones. We are grateful to the Parliamentary Archives for allowing us to reproduce material from the Lloyd George Papers.

Further reading

Andrew Blick and George Jones, Premiership: the development, nature and power of the office of the British Prime Minister (Imprint Academic, Exeter, 2010); At Power’s Elbow: Aides to the Prime Minister from Robert Walpole to David Cameron (Biteback, London, 2013).

Peter Hennessy, Whitehall (Pimlico, London, 2001).

John Turner, Lloyd George’s Secretariat (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009).

[1] Parliamentary Archives, Lloyd George Papers, LG/F/74/2/3.

[2] Parliamentary Archives, Lloyd George Papers, LG/F/74/2/11 p.1.

[3] Parliamentary Archives, Lloyd George Papers, LG/F/74/2/3.

[4] Parliamentary Archives, Lloyd George Papers, LG/F/74/10/4, pp.2-3.

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.