As Cuban as palm trees

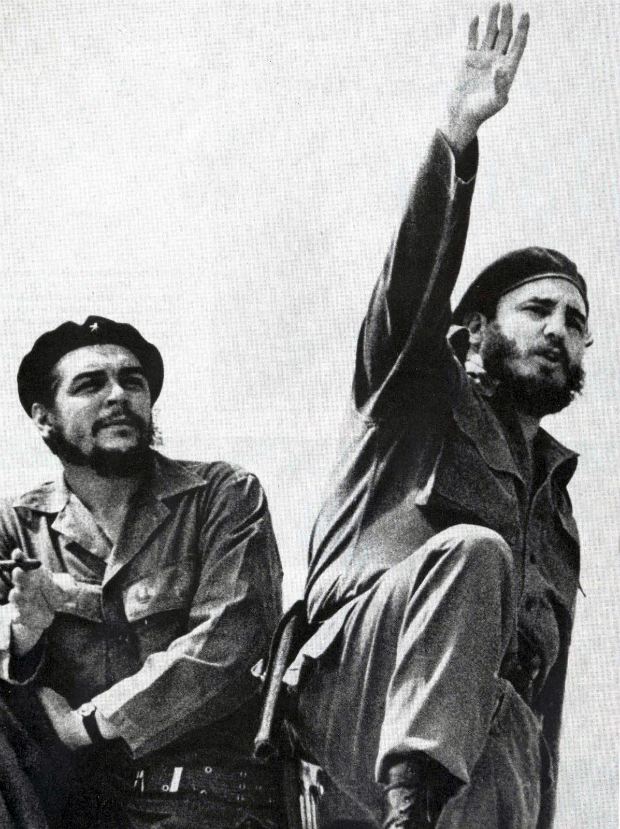

The death of Fidel Castro at the age of 90 on 26 November 2016 marked the end of an extraordinary life: head of the Cuban government from 1959 until he handed over to his brother Raul in 2008, Castro was the longest serving non-royal leader of the 20th century and survivor of more than 600 assassination attempts by the CIA. Castro may have ruled over a small island in the Caribbean, but he was to become a powerful international figure, his influence felt from Moscow to Washington, from Buenos Aires to Cairo, from Caracas to Luanda. The most dangerous crisis of the Cold War was played out in Cuba in 1962. And yet Castro described himself as being ‘as Cuban as palm trees’, and the success of the revolutionary movement he led with his brother and Che Guevara, seizing power as the dictator Batista fled the island, came as a surprise to almost everyone—Fidel included.

The Castro brothers had formed an underground movement in the early 1950s to try and overthrow the corrupt regime of the dictator Fulgencio Batista, under whose rule Cuba had become a haven for organized crime while the general population was brutalized. After an unsuccessful rising against Batista in 1953 the Castro brothers were jailed for 15 years, but were released after 2 and allowed to go into exile in Mexico. There they met the charismatic Argentinian doctor Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, who returned to Cuba with them and a small band of followers in 1956. Joining with mountain bandits, from their stronghold in Sierra Maestra Fidel and his followers smuggled in arms, mounted guerrilla raids, blew up bridges, kidnapped Americans and cut off the ports from which sugar was exported, damaging the economy. Batista finally fled on New Year’s Eve 1958, and Fidel, at the age of 30, entered Havana in triumph on 8 January 1959.

The eyes of the world were not on Cuba

In the broader Cold War context, the international focus in 1958-9 was on Europe and the Middle East, not Latin America. In 1958 Khrushchev rose to supreme power in the Soviet Union, swiftly removing opponents and bringing his own supporters into power. A twin strategy of building up Soviet arms while calling for a nuclear test ban and initiating disarmament talks, plus increasing the pressure on the West over the status of Berlin and a divided Germany, kept the US Government headed by President Eisenhower preoccupied, while providing ammunition for Eisenhower’s political opponents. The President himself was recovering from a stroke, and beset by internal political difficulties. The state of the US economy and allegations of corruption against advisers close to the President led to a heavy Republican defeat in the mid-term elections on 4 November 1958.

There were also major tensions between the USA and China over the status of Formosa (Taiwan), growing concern over Soviet influence in Egypt, and a proxy arms race in the Middle East as the US, Soviet Union and France supported opposing powers in the region. In July 1958, a coup in Baghdad overthrew the monarchy and led to the US and UK sending troops into the Lebanon and Jordan, a show of force intended to deter Nasser from becoming closer to Moscow. Meanwhile, the UK Government under Harold Macmillan was preoccupied with unsuccessful efforts to promote a European Free Trade Area (EFTA) as a rival to the newly-established European Economic Community. No one was paying much attention to Latin America, let alone to Cuba, which fell into Castro’s lap almost before anyone had noticed.

The only leader in town

The Americans regarded Latin America and the Caribbean as their back yard; Cuba was only 90 miles off the US coast, and a lot of Americans had business interests there. But Latin America had not been high on the agenda of the Eisenhower administration since 1954, when the Arbenz regime in Guatemala had been overthrown with CIA help. In the region American policy was perceived as exploitative economically and supportive of dictators, and on his Latin American tour in 1958 Vice-President Richard Nixon was met by hostility (and rotten eggs). Although he returned home to advise that more support was needed to prevent the spread of communism, little changed. The stage was set for Castro, the charismatic and dynamic leader of a broadly-based anti-Batista movement, to increase his pressure on a regime with that Washington was unwilling to prop up.

At first Castro received some support in the US; he was not yet an avowed Communist, and it seemed possible he would bring a welcome boost to Cuba and its economy. A week after his triumphal entry into Havana, US Secretary of State Dulles wrote to Eisenhower that Castro’s Provisional Government appeared ‘free from Communist taint’ with ‘indications that it intends to pursue friendly relations with the United States’. But Castro’s opposition to American economic interests, lack of interest in holding elections and programme of nationalization soon alienated the Eisenhower administration, which feared the example of a successful revolution might be emulated elsewhere in Latin America. By March 1960 Eisenhower had approved the creation of a government-in-exile in preparation for Castro’s fall; however, CIA confidence that Castro could be unseated quickly was misplaced.

Nixon gets it right

Before US-Cuban relations deteriorated badly, Castro visited the US in April 1959, though the visit was an awkward one and led to no meeting of minds. Vice-President Nixon commented: ‘whatever we may think of him, he is going to be a great factor in the development of Cuba and very possibly in Latin American affairs generally . . . we have no choice but at least to try to orient him in the right direction’ (FRUS 1958-60, vol. vi, p. 476). The first part of this judgement proved to be an understatement, but Castro was to remain resistant to ‘orientation’ until the day he died.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.