The allied invasion of Normandy initiated through the infamous D-Day landings in 1944 is one of the most familiar historical events in British history. Yet what is seldom recognised is that this was not the first time a large fleet of ships and transports carrying an invasion force had crossed the English Channel to the shores of northern France. Just over 600 years ago, in the late summer of 1417, a flotilla of at least 233 English and Dutch ships crammed with almost 11,000 soldiers made a similar journey to the Normandy coast. The route of passage had been cleared by an advanced naval force led by the earl of Huntingdon which had successfully defeated a Franco-Genoese fleet off the Seine estuary. The army disembarked not to the west of the River Orne as allied forces had done on D-Day but to the east, close to the mouth of the river Touques by the prosperous medieval port town of the same name. This marked the beginning of what quite literally could be described as Henry V’s ‘Norman conquest’ a feat accomplished between August 1417 and January 1419. During this time Henry successfully subjugated the Norman lands that his royal ancestors had lost two centuries earlier.

A New Strategic Approach

The invasion marked a watershed from previous campaigns launched against Valois France which were designed to inflict economic and military damage to undermine French rule and negotiating power. In contrast Henry planned and executed a more patient and deliberate strategy of conquest designed to sustain as well as extend English rule in newly won territories in Normandy.

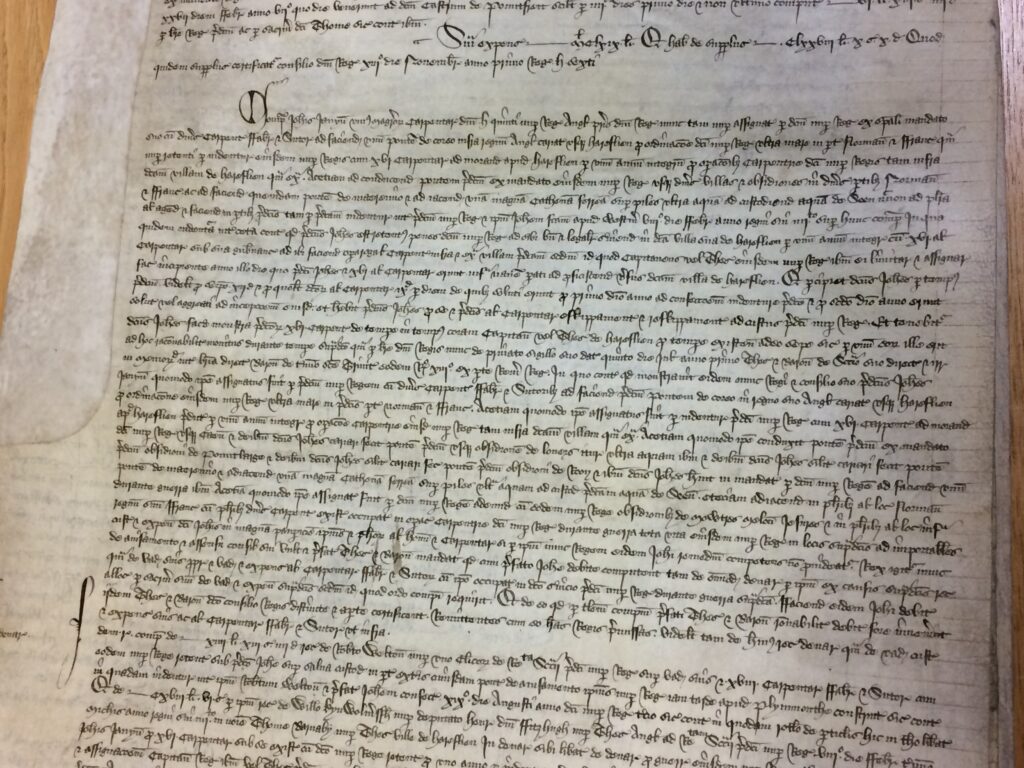

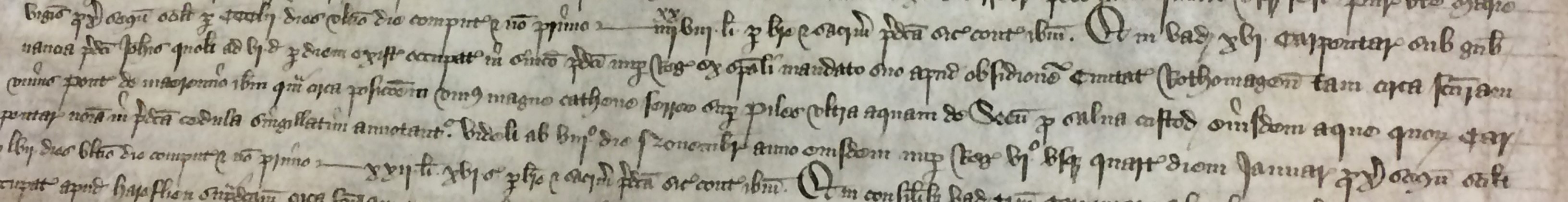

As financial records enrolled in the English Exchequer testify, Henry was prepared for a more drawn out and sustained campaign of siege warfare. These accounts reveal substantial payments paid to specialist craftsmen whose construction and engineering capabilities were crucial to the prosecution of siege operations. Their role and duties to some extent resembled those of the Royal Engineers today. For instance a payment of £88 was made to John Janyn, master carpenter, and eight other carpenters for the repair and maintenance of major bridges in the newly conquered towns of Caen, taken in September 1417 and Louviers and Pont de l’Arche seized the following summer. Paid almost a year’s wages each, their work would have been essential for ensuring supplies and troops were able to move unhindered across secure crossing points over the Orne and Seine rivers.

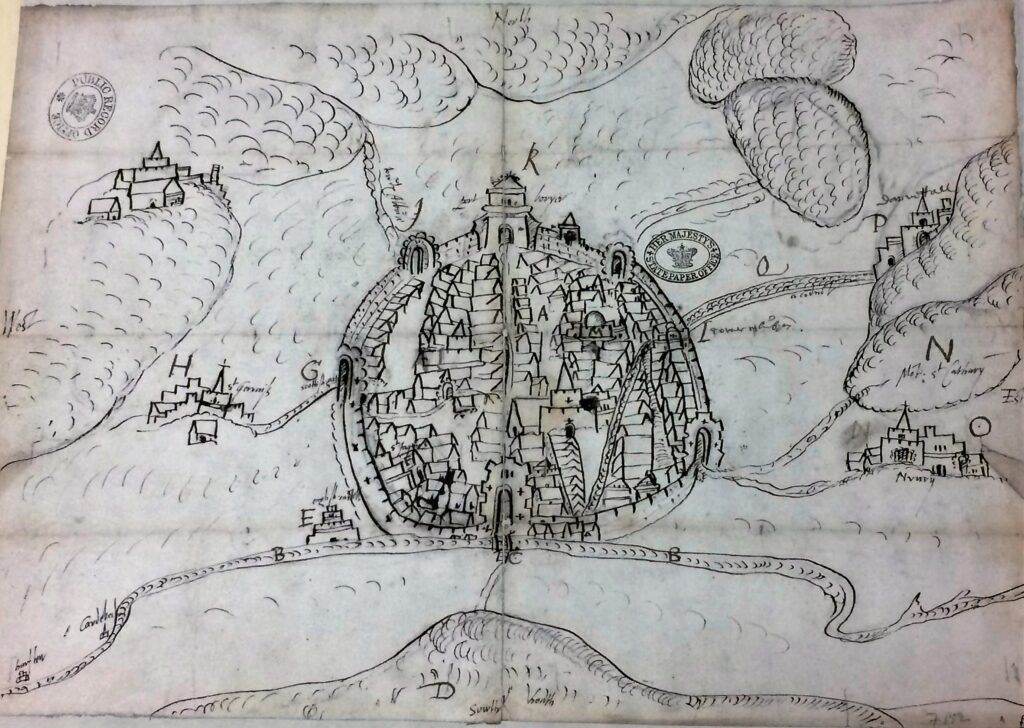

A further payment of wages to John Janyn and 16 other carpenters of £22, 16 shillings between 8th November 1418 and 4th January 1419 reveals their role in the siege of Rouen (29th July 1418- January 19th 1419). By the autumn of 1418, only Rouen, Normandy’s largest town with a permanent population of 20-25,000 stood between Henry and the subjugation of the duchy.[i] The accounts specify that John Janyn and his junior carpenters and craftsmen were required to construct a timber bridge and position an iron chain laid across the river Seine downstream from the city. This was part of prodigious efforts to ensure enemy ships could not leave or resupply the besieged town via the river and to provide greater security for English vessels on the river re-victualing the besieging forces. Henry even ordered vessels to be carried overland in order to circumvent the French held Seine Bridge and block any relief coming from upstream or inland of Rouen.

Administrative legacy

Perhaps the most potent legacy of Henry’s ‘Norman Conquest’ 600 years ago was administrative rather than military in nature. As part of Henry’s strategy of legitimacy and permanency, Henry revived an ancient set of administrative documents known as the Norman rolls (C 64) that had been established under his forbear King John at the beginning of the thirteenth century. They had come to an abrupt end in 1204 when the duchy was conquered by King Philip II of France. These rolls recorded letters patent (open) and close (where the letter was sealed), writs, mandates and other instruments issued under the great seal and relating to Normandy. Similar records for the English administration of Gascony (C 61, accessible online) had been generated since the mid thirteenth century, therefore the re-establishment of an equivalent administrative framework in Normandy was a step forward in establishing a more permanent English rule in northern France. For historians these records provide a vital window on the early years of fifteenth century English administration in the duchy and crucially yield evidence of royal business whilst Henry was campaigning in northern France between 1418 and 1422.

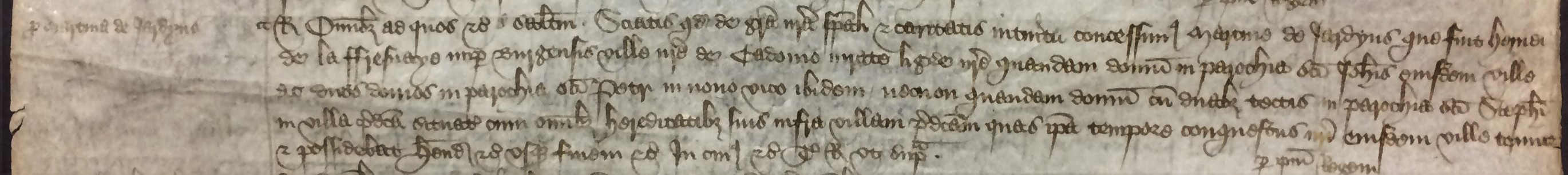

One of the earliest entries on the roll, dated 21st March 1418 at Bayeux was a grant to William Hotoft in tail male (succession of property to male heirs only) of the lordship of ‘Asseville’, and the manor of Herville [Herouville?], Caen (C 64/9 m.41). This entry is one of many grants of land and property that appear on the Norman rolls that were awarded to English captains, soldiers and settlers. Such substantial evidence of land re-distribution found in the records was part of Henry's strategy to consolidate English rule in Normandy and northern France.

At a council convened after the fall of Caen Henry made clear his desire that he wanted to be viewed as a legitimate ruler rather than as a conqueror to the native populace and this wish is also evident in the rolls. Entries for the 16th May 1418 record the return of houses and property to several named citizens of Caen including Martina de Jardyns, widow of Hervey de la Fresnaye, late burgess of Caen (C 64/9 m.28). Lands and property were restored to those Norman citizens who formerly acknowledged Henry as their rightful king though most of the greater Norman landowners and nobility chose to flee rather than yield. Their lands were confiscated and granted to men such as William Hotoft, mentioned above.

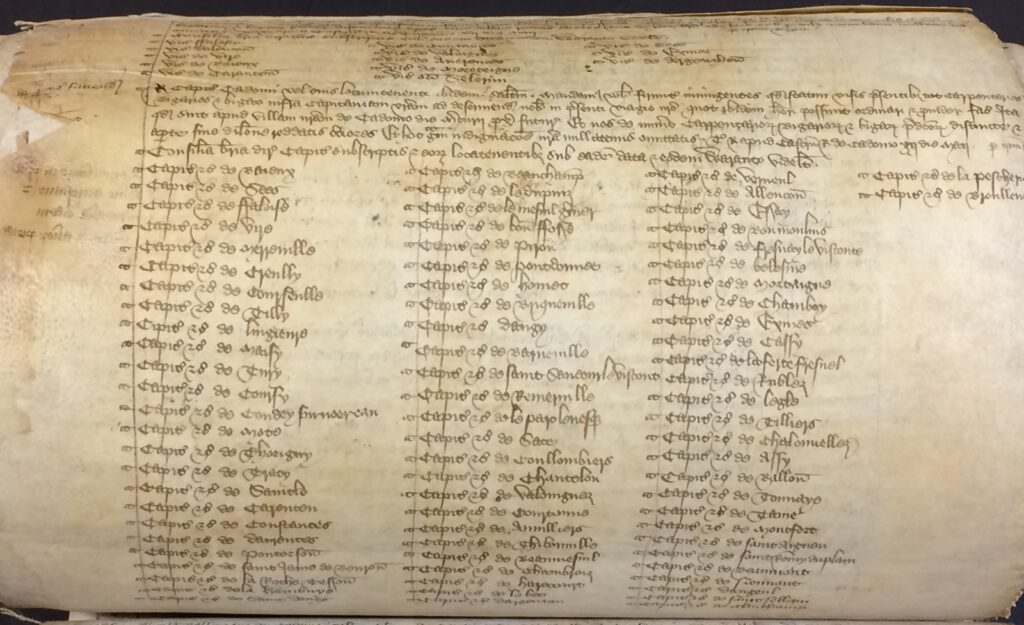

A final word on the value of these records is the evidence gleaned from royal mandates and orders to subordinate commanders and captains in the field which helps us to understand and chart the progress of the campaign to reduce Normandy from March 1418. The order seen below for instance, dated 12th May, 1418 is addressed to the captains of Caen, Bayeux, Sées and 79 other named French towns under English control to provide carpenters, carters and carts for the king's service most likely to support the logistics and siege operations of Henry's army. This reveals the extent of English conquests achieved over nine months of campaigning by the late spring of 1418.

The military legacy left by Henry V’s successful conquest of Normandy proved not to be the enduring triumph he envisaged. In the short term Henry’s military success personified the strength, unity and divine favour of his rule in stark contrast with the divided and ineffectual rule of Charles VI and the warring factions of the French court. It was also a factor in persuading the Duke of Burgundy to ally with England in 1419 and an important stepping stone on the road to the Treaty of Troyes (1420), the closest any English king would come to securing the prize of the French crown. This dream effectively died with Henry in 1422 but military expansion in northern France continued successfully for several years after the king’s death.

Nevertheless evidence of Henry’s administrative legacy in Normandy has endured to this day thanks in part to the surviving series of Norman Rolls (C 64) held at the National Archives. These records, now six centuries old, formed a major part of Henry’s strategy to consolidate his authority within the newly won territories in northern France, giving English governance greater stability and legitimacy. They stand as a surviving monument to Henry’s ability and tenacity in attempting to fulfil the long held desire of England’s medieval monarchs to rule as kings in France.

[i] Figures from J. Sumption, The Hundred Years War Vol. IV: Cursed Kings (London, 2016), p.584.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.

1 comment

Comment by Andrew F posted on

A very interesting window into Anglo-French medieval history.

These blogs are much appreciated!