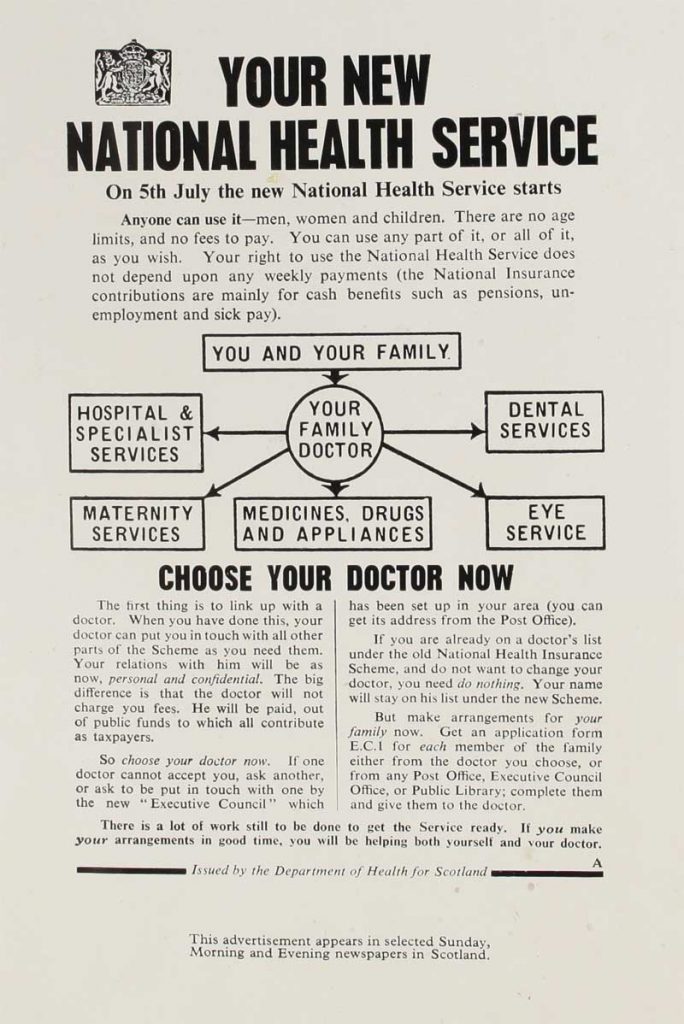

The National Health Service (NHS) is seventy years old today. Founded on 5 July 1948 by Clement Attlee’s Labour government, the NHS is now the most celebrated welfare institution in Britain. It regularly tops polls of what makes people ‘most proud to be British’ and featured prominently in the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympic Games. But where did the service come from and was it always this popular?

Pre-NHS Healthcare

Before the NHS, British healthcare was unevenly distributed throughout the country. If you were lucky enough to live near a prestigious teaching hospital – like St. Thomas’s in London – then you might receive excellent treatment. If you relied on a small cottage hospital (with a handful of beds), then perhaps not. Access to a General Practitioner (GP) also varied. Some areas enjoyed high-quality ‘family doctor’ services, while other parts of the country (particularly industrialised towns and cities) regularly suffered from a lack of doctors.

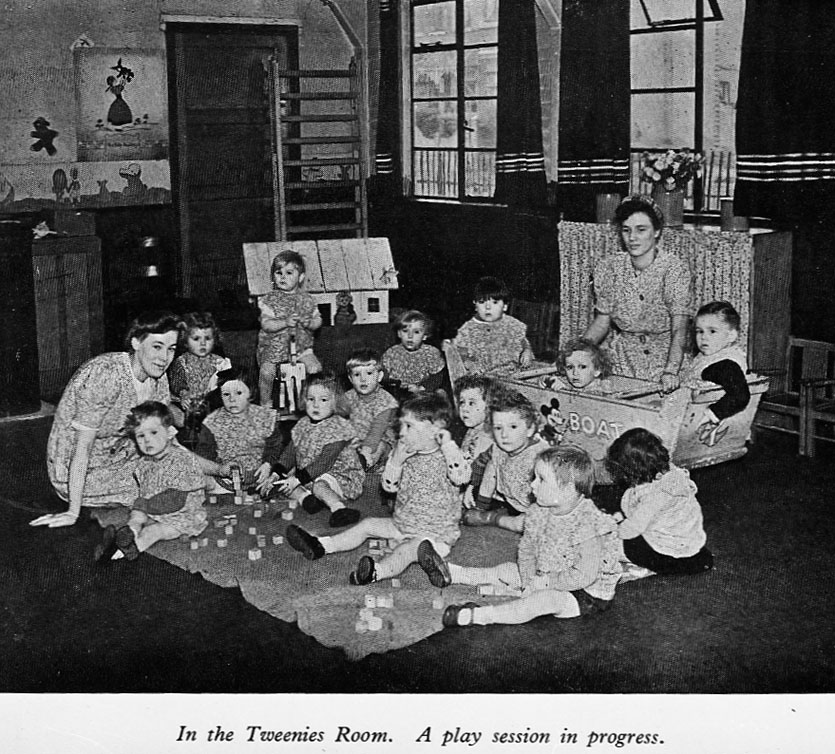

Payment for medical treatment depended on occupational status, class, gender, and age. Many working men possessed health coverage under the 1911 National Insurance Act, which provided access to a ‘panel’ doctor for a contribution from their weekly wages. ‘Dependents’ (wives and children), however, were not covered by the 1911 Act and had to pay out of their own pockets to see a doctor (typically 3 shillings and sixpence in the 1930s). As a result, women and children faced some of the harshest barriers to medical care in the interwar period. As national insurance depended on job status, the long term unemployed also often struggled to access affordable healthcare. Surprisingly, so could many members of the middle class. Many found paying private fees difficult and were disqualified for coverage under the 1911 Act if they earned above the wage limit.

Despite this patchiness, sizeable numbers of British people felt affection for the pre-NHS system. Many liked the charitable spirit of voluntary hospitals and their place in local communities. Millions of Britons enjoyed world-class medical care by contributing from their wages to popular voluntary hospital contributory schemes. Many local authorities ran impressive municipal hospital services. London County Council, for example, supplied the largest number of municipal hospital beds in the world by 1939.

The Origins of a ‘National Health Service’

For this reason, many British people viewed proposals to create a ‘national health service’ with scepticism. Opinion polls collected during the Second World War revealed no clear majority in favour of ‘state medicine’. Many expressed fears about losing the ‘personal touch’ in medicine if the government nationalised the hospitals.

This presented a serious challenge for reformers who thought a state-organised ‘national health service’ the best way to address gaps in the previous system and provide free healthcare to all. Activists and doctors had promoted these ideas in various guises since at least the Edwardian period. Beatrice Webb made an early intervention in calling for a ‘state medical service’ in the Minority Report of the 1909 Poor Law Commission. Though support for great involvement by the government in providing healthcare mainly came from progressive reformers like Webb, others played an important role in its conceptualisation. The 1942 ‘Beveridge Report’ popularised the idea and its author, William Beveridge, belonged to the Liberal Party. The Conservative-led wartime coalition government introduced the first parliamentary bill for a National Health Service in 1944. Different strands of political and medical opinion therefore recognised the need for extensive reform by the end of the Second World War.

The ‘Appointed Day’

After Labour won the 1945 General Election, Attlee tasked Aneurin Bevan with putting these ideas into practice. A charismatic firebrand from the valleys of South Wales, Bevan is best remembered now as the ‘father’ of the NHS. His struggles against the British Medical Association (BMA) are notorious in the history of the service for their bitterness, with insults hurled from both sides.

Though the Bevan-BMA dispute is usually at the forefront of historical writing on the beginnings of the NHS, we should not forget the contributions made by those around him. Civil servants also played a vital role in bringing about a gargantuan state institution that inherited and subsequently managed 1,143 voluntary hospitals with 90,000 beds and 1,545 municipal hospitals with 390,000 beds in England and Wales alone.

Enid Russell-Smith, a civil servant at the top of the Ministry of Health, kept a personal account of the onset of the NHS. She expressed anxieties about whether such a service could be achieved or whether the public would welcome it. Despite these efforts, in March 1948 she confessed to being ‘almost frightened by the vast mass of stuff there is to get through before July’. Russell-Smith’s civil servants worked hard to ensure the necessary paperwork and administrative structures were in place by the ‘appointed day’ of 5 July. By May, she raged at the ‘bloody-minded’ doctors and ‘revolting’ dentists that she had to negotiate with in long meetings at Bevan’s side. Like many who worked with him, Russell-Smith both admired and grew frustrated with Bevan. ‘He is really an astounding creature full of thunder + lightning’, she assessed, though ‘he altogether lacks the quality of reasonableness which counts for so much in English public life.’

When the ‘appointed day’ drew within touching distance, Russell-Smith articulated the sense of concern that many felt about the NHS’s chances of success, writing, ‘We shan’t really know how badly we have done until about the 6th July when no doubt an angry mob will be trying to burn down Whitehall’. With the public divided on the NHS and those responsible for implementing it understandably daunted by the prospect, it is in some ways remarkable the service got off the ground at all. The NHS’s beginnings are a far cry from its status today as a beloved British institution. Yet the determination of the service’s architects, and those who took up their vision afterwards, have helped ensure it reached today’s milestone.

Further reading

Virginia Berridge, Health and Society in Britain Since 1939 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Martin Gorsky, John Mohan, and Tim Willis, Mutualism in Health Care: British Hospital Contributory Schemes in the Twentieth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006).

George Gosling, Payment and Philanthropy in British Healthcare, 1918-48 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017).

Nick Hayes, 'Did We Really Want a National Health Service? Hospitals, Patients and Public Opinion before 1948', English Historical Review, Vol. 127, No. 526, (2012): 625-661.

Charles Webster, The National Health Service: A Political History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Special thanks to The National Archives, Kew and Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge for access to their primary sources.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.