In 1918, the death rate in Britain exceeded the birth rate for the first year since Government started maintaining records in 1837. Yet this was not due to the First World War, but to so-called ‘Spanish Flu’.

At the time, influenza was not a notifiable disease. Incidences did not have to be reported, either internationally or locally in Britain. Germ theory was not universally accepted and the understanding of viruses was still in the future. Flu symptoms were easily mistakable for several other illnesses, which is one reason why the epidemic’s worldwide death rate is unknown even now. Estimates vary from 50 to 100 million people.

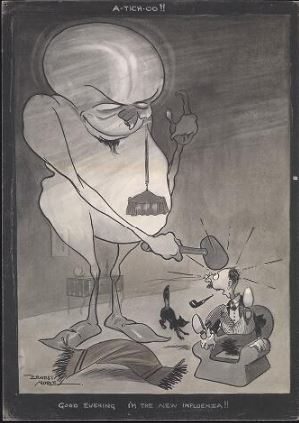

Reference: Wellcome Library no. 24069i

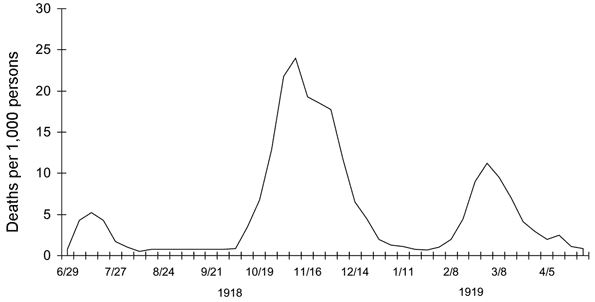

Three waves

Over 1918 to 1919 the flu struck in 3 waves. The first started in March 1918, reaching Britain in May. At the time the First World War was still raging and the press in belligerent countries was highly censored. Any information likely to impact on morale or indicate a weakness to the enemy was strictly prohibited. The same did not apply in non-combatant countries.

Because Spain was neutral the Spanish press was not subject to the same level of censorship as the press in the belligerent countries. News of an epidemic appeared in the headlines of Madrid papers in May 1918. This was one reason why its point of origin was assumed to be Spain. The first reference to the ‘Spanish disease’ was in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) in August 1918. The fact that the Spanish King, Prime Minister and various members of the cabinet fell ill sealed the international notion that the disease had originated in Spain. A hundred years later there are still several theories concerning the source of the disease, but no-one now considers it to be Spain.

The second, most deadly, wave of the disease struck Britain in October 1918 and continued through to 1919. It was probably brought over from France by servicemen, as port towns and transit points were particularly hard hit. At the time, health care in Britain was largely provided by local authorities, overseen by the Local Government Board (LGB). Their main concern was not health care provision but the operation of the Poor Law.

Although the death rate in Britain over the course of the pandemic was one of the lowest internationally, the flu pandemic still killed 228,000 people. Surprisingly, the matter does not appear to have been discussed by the Cabinet, even after the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, contracted it on 12 September. It was not even discussed in Parliament until late October 1918. Yet the warning signs were already there. Chemists experienced a rush on quinine, and graveyards had a backlog of burials. Most importantly, even the first phase had hit some cities especially badly, notably Glasgow, Sheffield and Belfast. There was also the memory of the ‘Russian flu’ of 1889 to 1892, where a more virulent form of the disease followed the initial strain.

Management of the disease

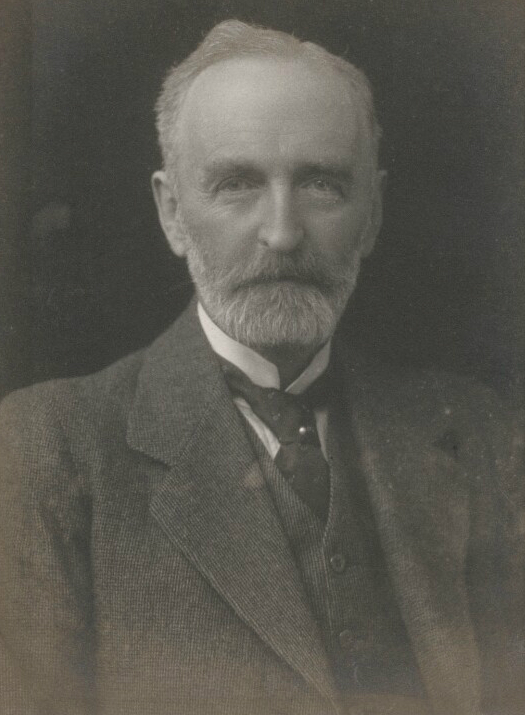

The armed forces had been monitoring cases. In fact, Walter Morley Fletcher, who was on the Army Pathological Committee, published a notice in the British Medical Journal in August 1918 requesting that observations about influenza should be sent to the journal. The Chief Medical Officer of the Local Government Board (LGB), Sir Arthur Newsholme, did not see the notice, but in the same month cancelled plans he had prepared for dealing with a resurgence of the epidemic, because of the requirements of the war. His strategy had proposed measures such as preventing large gatherings of people or overcrowding on public transport (where the disease could easily spread) and provisions for maintaining the production of munitions for the war effort. He did not issue any instructions to local authorities until 22 October. The LGB produced a film, Dr Wise on Influenza, which was distributed at the end of the second wave of the disease in 1919, but this was rather late, and insufficient copies were produced. Some local authorities and newspapers issued advice anyway. This ranged from sensible suggestions like isolating victims and avoiding crowds, to more questionable ones, such as eating lots of porridge and cleaning teeth regularly.

Reference: NPG x65720

Newsholme’s actions seem negligent with the benefit of hindsight, although it is unlikely that one person was solely responsible for the decision to postpone plans to deal with a resurgence of the epidemic. In August 1918, the disease seemed to be a spent force and the attitude at the time was to persevere until the end of the war. Few realised the threat posed by influenza or that rather than just affecting the old and the very young, this disease would particularly affect 20 to 40 year olds. The crowds celebrating the armistice exacerbated the spread of the disease by bringing large groups of people into close proximity.

Proposals for a Ministry of Health to prevent disease and coordinate health-care provision had been discussed by the Cabinet as early as summer 1917. Yet it would take until 1919 and a severe epidemic before this was established, and the nation’s health would come under closer central government scrutiny under the new Ministry.

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.

2 comments

Comment by Martyn Standing posted on

That's a fascinating and informative blog Tara, thank you!

Comment by Michael Glover posted on

An interesting update Tara. I remember Lives of the First World War an Imperial War Museum Project. One life I remembered died in 1919 after exposure to toxic gases in eastern war against Turkey, though based in a depot in Salonika. Sent home unfit for duty he came to our local town. His wife died earlier of ‘TB’ in 1915 and he and his brother joined up. He was invalided out in 1917 and sent home. His wife died of a similar disease about 1918 after the man’s return home. The man himself died in 1919 of TB. Most of the social conditions where they lived relate well to the weakened conditions which allowed the flu virus to escalate. The man has a lone CWGC headstone in a local churchyard. Given hindsight it is almost impossible to separate the death of this man and his family members from the build up to ‘Spanish’ flu, not just the effects of the war on him but the social conditions of the times. Being sure when or when the outbreak began is a lottery but quite predictable given current knowledge.