Every year we remember that the guns of the First World War ceased firing at 11am on 11 November 1918. We imagine universal relief at the carnage of war finally ending, at least in the victorious countries. The armistice was agreed at 5.10am on 11 November to come into effect at 11am. The news was conveyed around Europe within the hour. The original armistice was for a period of 36 days, after which it had to be renewed. This was done four times before the Treaty of Versailles was signed. The only problem is that the war did not completely stop at 11am on 11 November.

The Entente had already agreed armistices with Bulgaria on 29 September, the Ottomans on 30 October, and the Austro-Hungarian Government on 3 November. Germany was the last of the Central Powers to sue for peace. The Armistice with Germany was agreed to come into effect at 11am to allow time for the news to reach combatants. However, fighting continued in several places during and after that time, including on the Western Front.

General John Pershing, Commander of the American Expeditionary Force, did not approve of the armistice. Consequently he gave no instructions to his commanders to suspend any new offensive action during the remaining hours until 11am. This gave individual commanders latitude to determine their actions in the last few hours and in some quarters there was fierce fighting up to 11am which was difficult to stop. On 11 November alone were nearly 11,000 casualties, dead, missing and injured, exceeding those on D-Day in 1944. Over 3,500 of these were American. Pershing had to face a Congressional hearing to explain why there were so many deaths when the hour of the armistice was known in advance.

The message did not reach East Africa as easily as the Western Front. For 4 years British, Indian and local troops, joined by South Africans, Belgians and Portuguese, had been trying to capture Major General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, the German commander of 14,000 men. Although he had a much smaller army than the ones he was facing, his practice of targeting forts and railway lines meant he could not be ignored. Throughout the war his force caused British and Indian troops to be diverted from other fronts. The weather, the lack of supply lines and various other conditions caused a high death rate amongst local people in East Africa, particularly from diseases, the numbers for which can only be estimated.

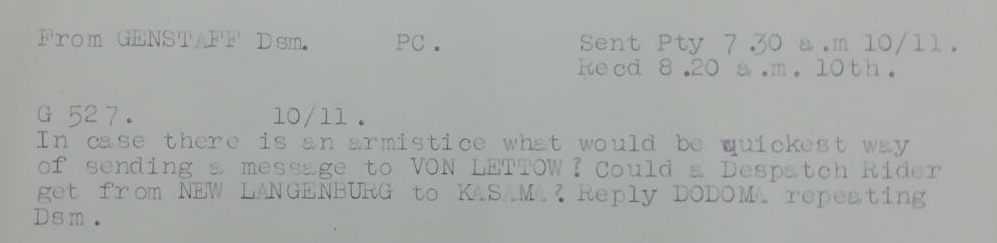

A telegram sent to East Africa from Europe could take between a couple of hours and a whole day to arrive. In anticipation of the armistice, on 10 November, the British General Staff sent a telegram to the force in East Africa asking them for the quickest way to get a message to von Lettow-Vorbeck. This was not straightforward as he had been evading the Allies for four years and his force was scattered. On 12 November, the two sides clashed again and von Lettow-Vorbeck only received notice that the war had ended later. There was a truce and in line with agreed instructions Lettow-Vorbeck formally surrendered his troops at Abercorn on 25 November.

The other area where the war did not stop was North Russia, in particular Murmansk and Archangel, the two main British bases in the region. Russia had capitulated in June 1917 after the Russian Revolution. Under the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed with Germany on 3 March 1918, the Russian empire had been split and its constituent countries restored to independence, but they were quickly occupied by Germany. After the armistice, the question of who controlled Russia remained. As winter approached, the British Government had to decide whether to retain forces in the region as with the extreme cold, there was the risk of being frozen in until the following year.

But even before November 1918, with Russia engaged in civil war, her former allies were concerned about Bolshevik ambitions. The newly independent countries, Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania, were also anxious, and appealed to the Allied governments for support. In Britain, thoughts of assistance were counterbalanced by fears of being drawn in to a foreign conflict with further loss of life. Part of the armistice agreement was that German troops in the Baltics should remain in the area as a precaution against Bolshevism. After the armistice, the number of allied troops in the region increased. The reasons for engagement had changed, but they still faced loss of life.

An armistice is a ceasefire, not an official end to war. Demobilisation of British, colonial and imperial troops did not finish until 1920, considerably longer than servicemen had anticipated. This caused more than one mutiny. Despite the unlikeliness that the Central Powers would resume combat, troops had to be prepared to fight again. Whilst we remember all those who died, and how 11 November represented the end of the war for most, this was not true for all and there was still fighting and dying after the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918.

- keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts

- follow our Foreign & Commonwealth historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians

- follow our Foreign & Commonwealth historians on Facebook @FCOHistorians

Further Reading

The National Archives, WO 15/465

The National Archives FO 175/1

Joseph E. Persico, 2005, Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour: Armistice Day 1918, World War I and Its Violent Climax