Nancy Astor is widely recognised as the first woman to take up a seat in the parliament at Westminster. But she was not the first woman to be elected. That place in history belongs to Constance Markievicz (née Gore-Booth) in what has been termed the ‘Khaki Election’.

Before the war

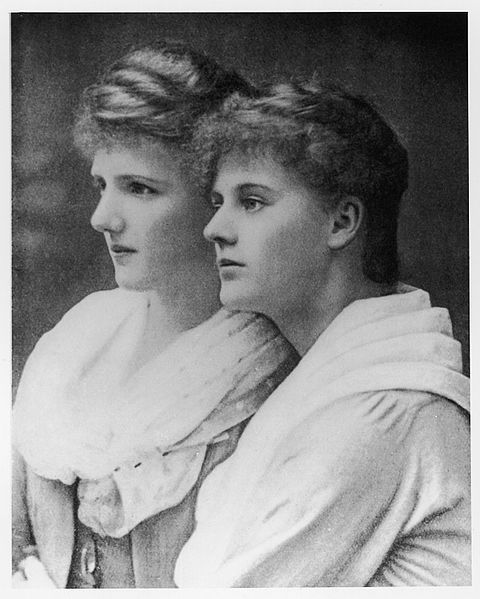

She was born in London in 1868, but spent her early years on the family estate in County Sligo, Ireland. It was during this time that she became politically aware both in terms of welfare for the poor and women’s suffrage. In 1893 she moved to Paris to study art. Whilst there she fell in love with a Polish count, Casimir Markievicz. They married in 1900, and lived in London and Paris, before moving to Dublin in 1903. They had a daughter together, but later separated. It was in this period she became associated with Irish nationalism.

In 1908 she supported the Barmaids’ Political Defence League, established by her sister Eva. The Licensing Bill going through parliament at the time, threatened to give magistrates the power to ban women from working in pubs. This held out the prospect of unemployment for thousands of women. The sisters successfully campaigned for the issue to be considered as more than a minor matter, canvassing effectively against Winston Churchill in a Manchester by-election. Parliament rejected the bill.

The war years

In 1916 in Ireland, the suspension of Home Rule until after the war was a contentious issue. Constance Markievicz played an active part in the Irish Citizen Army during the Easter Uprising, where she was second in command of the force which held St Stephens’ Green. Those who fought at the Green only gave up when they were shown the surrender order signed by the leader of the Easter insurrection, Patrick Pearse. Ironically, the British officer who accepted their surrender, a Captain Wheeler, was a distant relative of Constance Markievicz.

She was not the only women arrested after the rebellion although she was the only one to be court-martialled or held in solitary confinement. When brought before the court she was sentenced to death. Despite this, she proclaimed that she did not regret her actions. The officer commanding the court martial procedure, Lieutenant General Sir John Maxwell, commuted her sentence to life in prison because she was female and the British Government were concerned about the potential negative publicity. She was released from prison in 1917 as part of a general amnesty, but in May 1918, she was jailed again for her part in anti-conscription activities. In April 1918 the British Government tried to introduce conscription in Ireland; it was not a popular move and the petition against it produced two million signatures.

The khaki election

On 14 November 1918, the Government announced that there would be a general election to be held exactly a month later. The timing was designed to ride on the wave of war fever. Parliament was dissolved on 25 November.

Although voting took place on 14 December – the latest day of the year a General Election took place in the twentieth century - the count was delayed until 28 December to allow time for the votes of men serving overseas to be considered. Even so, many servicemen were unable to vote, which may be why this election had the lowest voter turnout of any in the twentieth century. It was also the first election since the extension of the franchise to women over thirty. The age qualification meant that they would still be a minority of the electorate. This, combined with the extension of the vote to all men, meant that the Irish electorate expanded from 700,000 to nearly 2 million. Interestingly, pundits estimated that women did not vote differently than men.

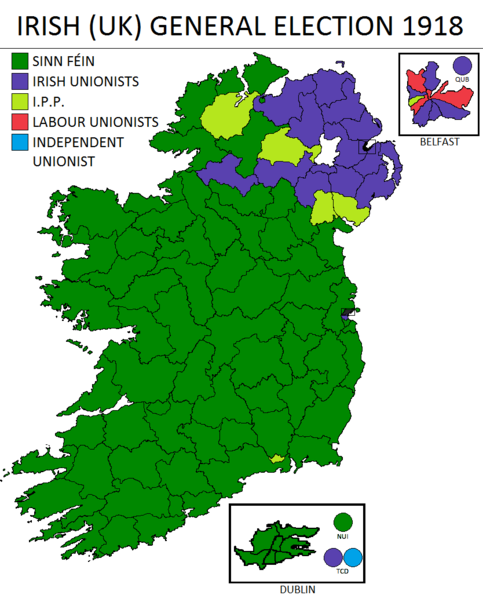

While in prison, Constance Markievicz ran as a candidate for Sinn Féin in the St Patrick district of Dublin. 17 women stood in the 1918 general election, including Emmeline Pankhurst. Constance Markievicz was the only one who was elected. Like her, another 47 Irish MPs were elected from jail.

She won two thirds of the vote, standing against two nationalist candidates, making history as the first female MP to be elected to the House of Commons. As a Sinn Féin MP however, she was elected on a mandate that she would not take up a seat in Westminster, in line with the party’s stance. The Irish Parliamentary Party, which had been the dominant party in Ireland in the previous election in 1910, lost nearly all of their seats. Sinn Féin won 73 of the 105 seats in Ireland, hastening independence. In 1919 Markievicz became the first Minister of Labour as well as the only woman to serve in the newly-formed Dail Eireann (Irish Parliament), until she left the government in protest against the Anglo-Irish treaty.

Why was she the only woman elected? Women were (sometimes) wrongly associated with pacifism, which was certainly not true of Constance Markievicz. In some cases, the seats women contested were considered unwinnable. For a few, the support base consisted of women under the age of 30, who would not have been eligible to vote.

Even aside from her political beliefs, her personal qualities would both attract and repel people today. She rejected the opportunity to live a quiet life of luxury in order to be politically active, but left her parents to bring up her daughter so that she could do so.

To mark the centenary year of her election, a portrait of Constance Markievicz by Polish painter, Bolesław von Szańkowski, has been displayed in the House of Commons. This portrait is now part of the Parliamentary Art Collection.

- if you are interested in our work then feel free to read our blogs on GOV.UK

- keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts

- follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians

4 comments

Comment by John Harvey posted on

"Interestingly, pundits estimated that women did not vote differently than men."

Why did suffrage make so small (if any) immediate impact on voting?

Comment by Tara Finn posted on

Good question! Certainly married women were encouraged to vote for the same candidate as their husbands would have done. Of course, not all women were in favour of women's suffrage, some were actively opposed to it. Like with men, there were multiple factors that determined what party women would vote for. As not all women were entitled to vote, it meant that in any constituency women voters would have been the minority. Constance Markievicz was not elected because she was a women but because of what she stood for.

Many thanks,

Tara

Comment by John Harvey posted on

Thanks

Were there any initiatives to get women to vote for women's issues?

Comment by Tara Finn posted on

The Women’s Party, formed in 1917, lead on women’s issues. You may find the article below of interest.

https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/portal/files/3601246/The_Women_s_Party_of_Great_Britain.pdf