The Armistice Agreement with Germany was signed on 11 November 1918, but the Peace Conference did not start proceedings until 18 January 1919. With so much at stake, why did it take 2 months for discussions to start?

Several allied countries had been planning for the peace talks before the end of the war. They produced maps and documents about the history and geography of the territories that would be discussed. But these preparations could only be general until the end of the war. By November 1918 many of the belligerent countries on both sides faced significant domestic issues. In Europe, the most virulent wave of the influenza pandemic that killed more people than the war was at its peak.

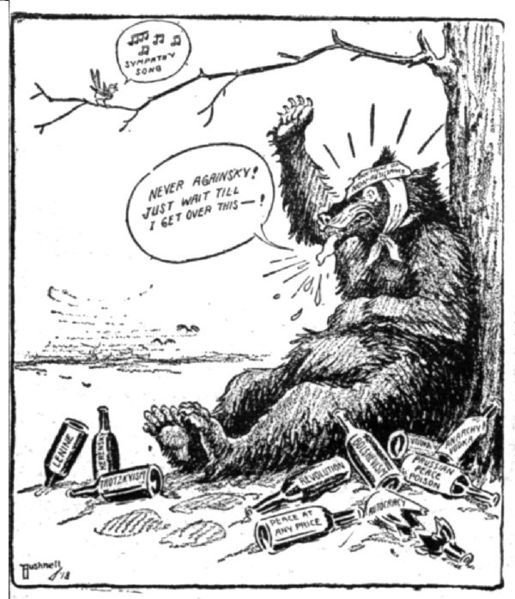

A major concern for the British Government was reviving the economy and returning men to production. There were logistical challenges about how many men could be demobilised at a time, yet sustain defence requirements and not create sudden unemployment. Britain was also responsible for demobilising men from the colonies and dominions. The Russian Civil War was intensifying and Britain, France and the US were providing resources to support the White Russians against the Bolsheviks in the fight to retain independence in countries in Eastern Europe. The German ceasefire, as it was not a surrender, meant that at least in theory there was a risk that the war could be resumed. In practise, few countries, and none that had fought for four years, were ready to resume full scale war, but the principles in the armistice agreement aimed to ensure Allied military superiority.

Before talks could commence the delegates needed to travel to Europe from around the world. US President Woodrow Wilson landed in France on 13 December and others came from much further, such as Japan and Australia. Wilson needed time to recover from the long journey, considering the precarious state of his health. He also needed the opportunity to talk with other leaders prior to the conference. The day after he arrived, Britain held a General Election. There had not been an election since 1910 and the Government argued that one was necessary in order to have the authority to negotiate at the conference. Counting the votes was postponed until 28 December, to allow returns from servicemen overseas to be included. As Britain would be one of the main powers at the conference, this inevitably meant formal proceedings had to be delayed until a new government had been formed. Lloyd George was re-elected, which made the situation easier in terms of continuity.

During the war, many foreign ministries lost influence to armies and war cabinets. The preparations for peace were made by different government departments, each with their own interests and little co-ordination between them. This lack of consultation within states was not just a problem in Britain, but also in France and the US. Combined with the contributions from other countries, this meant that the conference would need to consider a vast quantity of evidence.

An important decision was where the conference would take place. Many countries wanted this to be on neutral territory. Geneva was specifically mentioned. This presumed that all sides would meet and discuss terms. However the Allied powers, and France in particular, had other ideas. Their idea was that the conference would work out the preliminaries with German representatives only being invited after that point. Much of the Allied war effort had been co-ordinated in France, where there had been so many losses, so logistically, staying in Paris was simple.

There were other decisions to make too, such as the official language for the conference. During the war, French and English had held equal status in the Supreme War Council. French had been language of diplomacy for centuries. With America at the negotiating table there was a stronger case for English. Italy argued that if English was to have parallel status at the talks, Italian should rank equally. In the end both the English and French texts were deemed authoritative.

On 12 January 1919 the ’Big Four’, Britain, France, Italy and the US, met in what was supposedly a conversation between these countries. In practice, it was like a continuation of the Supreme War Council. The representatives from the 4 powers were joined the next day by the delegation from Japan. The purpose was to decide the framework within which the evidence would be considered, including committees and commissions. Russia had no place at the conference.

The delay was not all negative. Some of the now independent and newly created countries, notably Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania, and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later formally known as Yugoslavia), needed time to constitute governments and appoint representatives. The British and French also used the time to start co-ordinating the approaches within their own governments.

The large plenary sessions began on 18 January. Only six meetings would be held before the treaty with Germany was signed in June 1919. The delay in holding the conference was partly to enable the British Prime Minister to have the authority to represent the country. Yet even though participants came from near and far, in the end the process was hardly representative.

Source: Temperley, H.W.V (ed), (1920) A History of the Peace Conference of Paris, volume 1.

- if you are interested in our work then feel free to read our blogs on GOV.UK

- keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts

- follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians