The descriptions 'the sick man of Europe' and 'the British disease' plagued the UK’s economy and industrial outlook in the 1950s through to 1970s. Economic historian Nick Crafts has summed up the symptoms of ‘the British disease' as including 'inadequate management and dysfunctional industrial relations'.1 On winning the 1964 election the new Labour government adopted an interventionist industrial policy. These policies reached their peak in 1968 when the Industrial Reorganisation Corporation (IRC), attempted to restructure swathes of UK manufacturing.

White heat

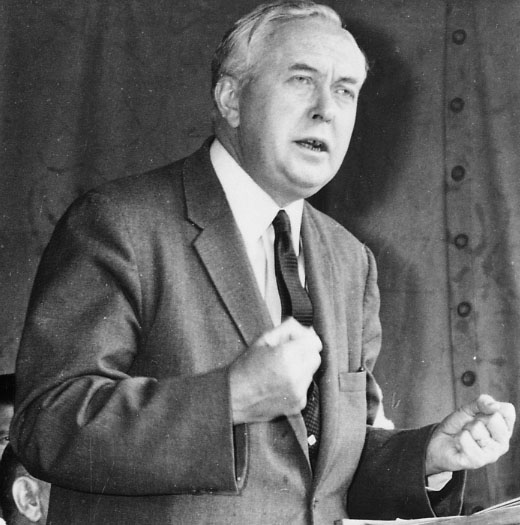

The foundation for the IRC’s interventions was the optimistic sense that government could create firms which were national champions and could compete on a global basis, not by nationalisation but by promoting amalgamation. Harold Wilson’s oft-cited speech on the ‘white heat of technology’ recognised the importance of new technology, and alongside the creation of a National Plan, paved the way for the IRC’s activities.

The specific solution to the problem of industrial modernisation was articulated through a memo written by an industrialist, Mr B.R. Cant, who worked for an engineering subsidiary of Powell Duffryn Coal Company. He noted that the problem with British industry was that of competition, and in particular the inability of enterprise to capture overseas markets. The output of many firms resembled large multi-product conglomerates and hence lacked the specialisation necessary for sustainable economies of scale.2 A more efficient industrial sector would help the parlous balance of payments position by encouraging exports. This could be managed by the government encouraging mergers, and to this end the IRC was established as a government 'merchant bank' that was able to broker deals and in some cases invest with its own resources.3 The aim was to facilitate the creation of firms that would be able to compete on the international stage. The government wanted to avoid any notion that this would be ’nationalisation through the back door‘ so the IRC was to be very much at one remove from government.

The IRC was promoted through a White Paper and established in 1966. The Department of Economic Affairs (DEA), which had been established as a counter-weight to the Treasury, was the sponsoring department. The DEA worked closely on this initiative with the Ministry of Technology (MinTech, with Tony Benn as its minister) and the Board of Trade (of which Anthony Crosland was the President).

Three new giants

The IRC was small, with about 30 on the staff reviewing and meeting companies; these included Geoffrey Robinson, later of British Leyland and Tony Blair’s Government, and Alistair Morton, who would go on to lead the Channel Tunnel construction project. The head of the IRC was Sir Frank Kearton, head of textiles giant Courtaulds, who was followed in the role by Sir Joseph Lockwood, chairman of electronics firm and music publisher EMI.

1968 represented the peak of the powers of both the IRC and Mintech. In that year these two government bodies finalised the restructuring of the firms which represented, it was hoped, the future of British mass and high technology manufacturing. The three major outcomes were:

- The creation of British Leyland (BL), where the IRC, with the support of Tony Benn, engineered the takeover of the mass car manufacturer BMC with its Morris and Austin by the smaller Leyland, a successful truck manufacturer which also owned Triumph and had taken over Rover in 1967. Collectively the new firm employed 250,000 people and dominated UK-owned car manufacturing.

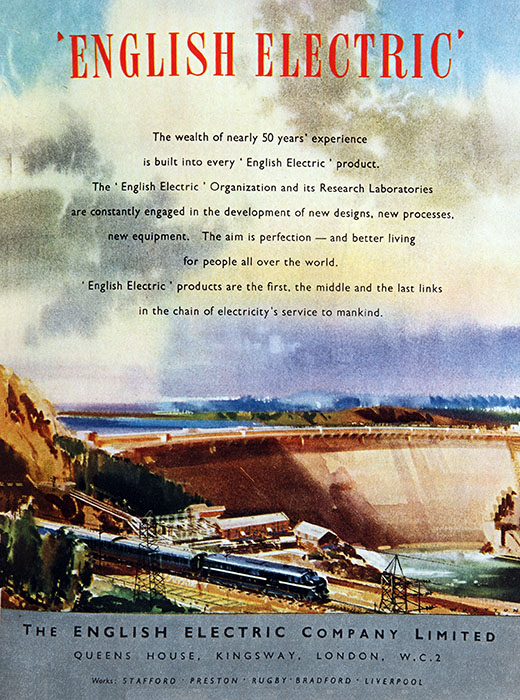

- The takeover of the iconic English Electric Company by the General Electric Company (GEC, not to be confused with the US-based GE) to create a giant electrical and electronic enterprise of 230,000 people which owned brands such as Marconi and Elliott Automation, leaders in the most advanced electronic products. In 1967, with IRC support, GEC had already acquired the other major UK electrical company, Associated Electrical Industries (AEI).

- The creation of International Computers Ltd (ICL) supported by the Ministry of Technology brought together English Electric’s computer division with the much more successful business computers firm International Computers and Tabulators (ICT), employing 35,000 people in what was the largest computer firm outside the US and the only major one not to fundamentally base its computer architecture on a US design.

Half a million jobs were directly reorganised with potentially the same number in the associated supply chain. It was intended that these straightforward mergers would be guided through by the IRC with overtures made to the Board of Trade not to refer the deals to the Monopolies Commission.

However, the outcomes were not what had been imagined. The new companies were neither specialised nor highly integrated and did not necessarily act in the manner expected of them. GEC was the perfect example of this. The IRC envisaged a future for GEC as the largest high technology engineering company in Britain, because it was enamoured of its manager Arnold Weinstock. He led his company through strict financial controls and to the IRC he represented modern managerialism. However, GEC lacked a clear strategic focus which would give it the ability to achieve economies of scale, nor did it have an eye to exporting. In 1969 a senior GEC manager told the IRC that what had been created was effectively 180 medium-sized companies.4 So much for scale!

As for exporting, the Board of Trade, a key stakeholder in the IRC's activities, expressed doubts that the right choice had been made. In 1969 it noted that while AEI and English Electric had been very active exporters, GEC had not.5 One of GEC’s first actions on taking control of English Electric was the closing of its export office in Japan. It was at this point that the Board of Trade realised that they had been bested as part of GEC’s strategy to avoid recent monopolies legislation. The former were only interested in profitable business, rather than exports per se and the government had no policy recourse to force the matter, though they should have been aware of this from their earlier analysis of GEC lack of interest in low margin exports. This was a clear setback to the IRC’s vision of industrial intervention.

A turning point

GEC, BL and ICL would remain UK industrial powerhouses for twenty to thirty years, but each met its end, GEC because of its decision in the 1990s to sell its core businesses and to use the cash mountain generated to refocus as a telecommunication firm. The bursting of the telecommunications and dot.com bubble devalued the many acquisitions the firm had made in the telecoms field and ended the direct history of the UK’s largest engineering firms. In the 2000s the descendent of BL, by then called MG Rover, and ICL would cease to be standalone companies. Nevertheless, the UK is littered with the remnants of these firms. BAE acquired the defence business of GEC and some electrical businesses survive under other ownership. Minis, Jaguars and Land Rovers are still made, but with different owners, while the service division of ICL is still involved in the UK technology services space under the ownership of Fujitsu.

Overall, it is hard to argue that these firms, where their remnants survive at all, are not greatly reduced in terms of their stature in the economy, the scale of their operations and the size of their workforce. The 1968 reorganisation is overlooked as the turning point of British manufacturing and technology. Managerialism and government cajoling was meant to deliver firms able to lead the world in terms of the ‘white heat of technology’ and ensure the UK remained a leading exporter of complex high technologies. Crafts notes that industrial relations and indulgent management were at the heart of the ‘British disease’. To this we should add the damage caused by a blind faith that large enterprises would automatically improve competitiveness, without reference to underlying product markets - this was a failure of government understanding.

This blog post draws on the recent publication by Dr Roy Edwards and Dr Anthony Gandy: Enterprise vs. product logic: the industrial reorganisation corporation and the rationalisation of the British electrical/electronics industry, Business History (2018).

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.