German anger at the Treaty of Versailles between the wars is well known. Hitler, in his rise to power, exploited this deep resentment. So how did such a contentious document come into existence and why was it signed?

Responsibility for drafting the treaty, rested with the ‘Big Four’ (the US, Britain, France and Italy). The conference started discussing the peace terms on 12 January 1919. The first time a German delegation was invited to participate in the peace conference was in April. The German Government was instructed to send plenipotentiaries, representatives with the authority to sign the treaty. The delegation stayed at the Hôtel des Réservoirs, where the French leaders resided in 1871 when negotiating with Bismarck.

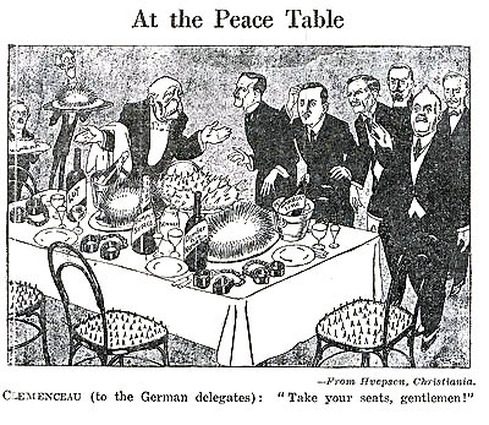

The draft document was presented to the Germans on 7 May, the anniversary of the Lusitania sinking. The atmosphere was tense, with diplomatic courtesies barely observed. Neither the treaty nor the conference were about reconciliation.

The Big Four had different aims:

- France, led by Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau: to combine reparations with territorial losses in order to prevent Germany from rising again

- Britain, led by Prime Minister David Lloyd George: to punish Germany, as per the mandate on which the new government had been elected, but also wanted Germany to be strong enough to prevent the spread of Bolshevik Russia

- The US: President Woodrow Wilson was trying both to prevent retribution, whilst satisfying domestic political pressure which sought a return to isolationism

- Italy, led by Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando: to acquire territory from the former Austro-Hungarian empire. Germany was not their main concern

President Wilson’s task was additionally complicated since his physical strength was weakened from a bout of so-called Spanish flu. Both Britain and the US were conscious of the strength of Germany’s pre-war manufacturing and trading and wanted to retain Germany as a trading partner. But as well as disagreement between delegations, there also a lack of unity within them.

The first 26 clauses of the draft treaty covered the establishment of the League of Nations, an organisation intended to promote and keep the peace. This was ironic as Germany was initially excluded from membership, with the intention that they would be invited after a probationary period.

From the first, the German government, led by President Friedrich Ebert, disliked the draft. The German press agreed. On 29 May, the German delegation presented a 434-page counter-proposal. The essential criticism was that the treaty was not based on President Wilson’s 14 points. Germany argued that it had agreed to the armistice on the understanding that these would be the basis of the peace agreement. Britain felt that the 14 points had actually constrained the treaty and prevented it from being more punitive. Wilson himself contended that the treaty did not violate his points.

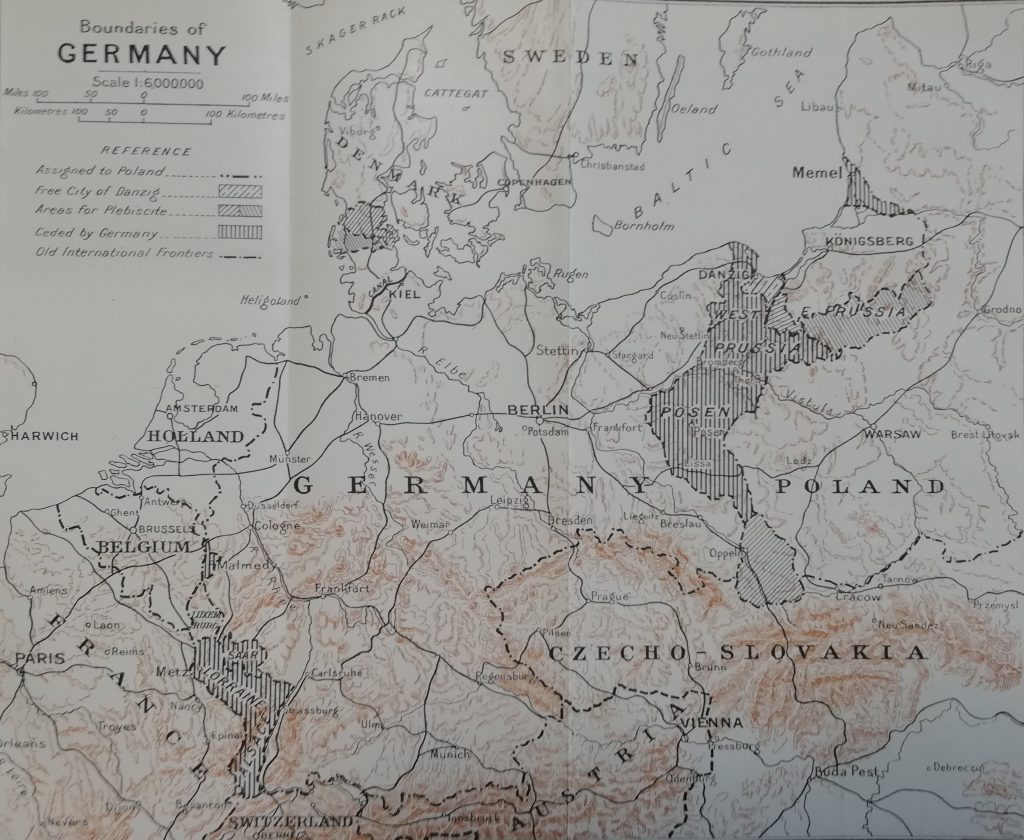

Three principles in particular caused consternation. The first of these was the boundary changes. America had been a champion of self-determination. Yet, according to the Germans, the territory taken from them handed large numbers of German-speaking peoples to other countries. The second hated point, Article 231, was dubbed ‘the war-guilt clause’, attributing responsibility for the war to Germany. In addition to national humiliation, this provided the basis for the third point of contention, reparations. The exact amount was to be determined by a committee, but would be at least 20,000,000,000 gold marks. This would be difficult to pay considering the industrial territories that Germany would lose.

The allies replied to the German protests on 16 June. The German delegation were given 5 days to agree to sign. If they refused, Article 2 of the Convention extending the Armistice agreement would come into force, entitling the Allies to resume hostilities. The delegation refused to sign. At 1:10am on 20 June, the German Cabinet resigned in protest. The Allies extended the time for agreement by 2 days.

On 21 June the German Navy, interned at Scapa Flow, scuttled the fleet, rather than hand over their ships. At the same time, President Ebert, who had remained in power despite the ministerial resignations, was quickly assembling a new cabinet to vote on the proposed treaty. He realised that the treaty was unpalatable to Germany, and checked with the Chief of the German General Staff, Paul von Hindenburg, whether the army would be in a position to resume fighting. The response was that it would not. On 23 June the Cabinet agreed to sign and the information was conveyed to the treaty committee. In addition to the fact that Germany was in no position to resume fighting, the British naval blockade was still in place.

The Germans were not the only ones unhappy with the treaty. Some members of the American delegation complained that it was not a peace treaty. General Jan Smuts, later South African Prime Minister, was openly critical of it on similar grounds. Lloyd George’s memoirs indicate his disquiet with the treaty. However, there was no appetite for restarting negotiations.

The logistics of signing the treaty still needed to be organised. The ceremony itself was full of historic symbolism. The treaty was signed on 28 June, the 5th anniversary of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The ceremony took place in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, where the treaty concluding the Franco-Prussian War had been signed.

There were some changes to the earlier Allied position: there would be plebiscites to determine the nationality of Schleswig, Upper Silesia, Eupen and Malmedy, East Prussia and the Saar region. A few elements of the treaty were not readily enforced.

The most notable of these was the demand that the (former) Kaiser should be tried for war crimes. He had emigrated to the Netherlands on 10 November. Despite pressure, the Dutch Government refused to extradite him.

The Treaty of Versailles came into force on 10 January 1920, although decisions about reparations and from plebiscites and were still to be made. The treaty would have repercussions for history. But much of the symbolism involved in the ceremony looked back much further than 1918.

Keep tabs on the past: sign up for our email alerts

Follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians

1 comment

Comment by John Tomlinson posted on

Thanks Tara, interesting read. I always wonder what might have happened if Asquith had led negotiations on behalf of the UK, either as PM or some other position - his biography suggests that he might have been less punitive in negoations