Many visitors to London and people working in Westminster walk past an empty tomb each day. But how many people recognise it for what it is?

After the Armistice in November 1918 Britons were mourning the war dead as well as celebrating the end of the fighting. On 9 May 1919 in anticipation of the end of the peace conference talks, Britain established a Victory Committee to plan an official celebration. Lord Curzon, who later that year became Foreign Secretary, led the committee. The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919 signifying the official end to the war. Victory Day would be on Saturday 19 July. There would be a parade in London, and local events around the country to mark the occasion.

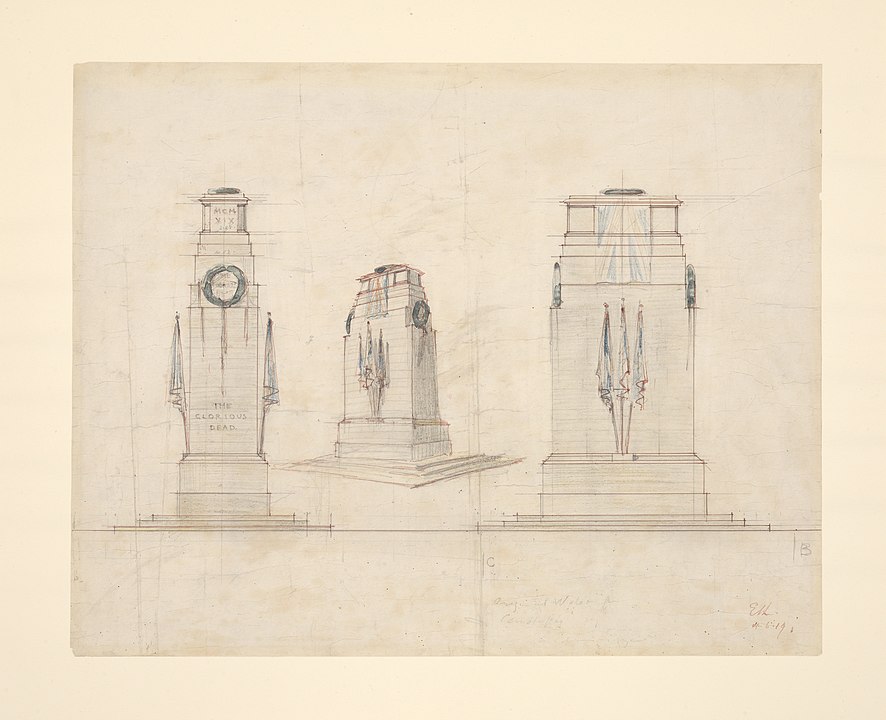

Designing the memorial

At the beginning of July 1919, the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George formally approached Sir Edward Lutyens to design a raised platform that would hold a tomb. This would be situated on Whitehall. The construction would mark a spot near the end of the parade. Lutyens designed the cenotaph (meaning ‘empty tomb’ in Greek). The original structure was made of wood and plaster and was temporary.

At the time the country was still struggling with the question of whether to repatriate the bodies of those who had died overseas. Wealthy families were initially able to bring back the bodies of their loved ones, but repatriation was not an option everyone could afford and many of the dead had no known grave. For the families of the missing, there was no geographical focus for mourning. Fabian Ware and the Imperial War Graves Commission stopped the practice, to emphasize equality in death.

Victory Day

Within an hour of the start of the parade, the base of the Cenotaph was covered in wreaths. Nearly 15,000 allied troops marched past it in the parade, and many others paid their respects there, including the widows of the fallen.

The public response was so profound that the newspapers quickly started asking whether a permanent structure could be erected. Some thought it should be situated elsewhere, away from the bustle of the traffic, but Lutyens was adamant: it had been consecrated in Whitehall and should remain there. On 30 July 1919 the Cabinet had agreed that there would be a permanent memorial, where the temporary one had been.

The new structure was constructed from Portland stone and was unveiled by King George V on Armistice Day, 11 November 1920. It was designed to be an exact replica of the temporary structure. As with the temporary construction, there were no names or religious symbols upon it, in order to represent all those of the Empire, from many faiths, who fell. However, the tomb of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey, unveiled on the same day, did have Christian references upon it.

All is not quiet

Not everything was peaceful on 19 July, though. Some veterans objected to the Victory marches and celebrations. Their suffering had not ended with the war, but continued afterwards with the challenges faced by servicemen readapting to society. Spending money on the dead was another point of contention. Many veterans argued that looking after the living would be a better legacy. One of the worst manifestations of this discontent took place in Luton, reflecting both wider unhappiness as well as specific local problems. Other disturbances occurred in Swindon, and Bilston, (near Wolverhampton).

According to the Borough of Luton Roll of Honour 1,284 men from Luton lost their lives in the war, none above the rank of Captain. No ex-servicemen had been included in the planning of the local commemorations. The Mayor of Luton, considered by some to have profited from the war through manipulating food prices, planned a celebratory banquet for Victory Day. His selected guests would attend free, paid for out of civil funds, with anyone else who attended having to pay. The price was beyond most ex-servicemen and women were also excluded. A veterans’ group, which had requested permission to hold a drumhead mass in Wardown Park, were refused, which only made matters worse.

Problems develop

The problems on 19 July started when the procession reached the town hall. The small official group had been joined by a number of ex-servicemen. As the Mayor read out the King’s proclamation, the people booed. They demanded an explanation for the refusal about Wardown Park, but none was given. The crowd surged towards the town hall and by force of numbers overpowered the police protecting it. They burst through the doors and headed for the Assembly Room, which was set for the banquet. After smashing up the furniture they were evicted from the building by police.

Trouble resumed that evening when a large and determined mob returned to the Town Hall. As the fireworks commenced at the other end of town, people started throwing bricks at the town hall and lit bonfires outside the building. With the addition of petrol and fireworks, it became an inferno. At one point, a piano was pulled out of a nearby music shop and the crowd accompanied the blaze to the tune of ‘Keep the home fires burning’. Firefighters were initially kept from tackling the fire, and ultimately the building was destroyed. Nearby shops were damaged and looted. At 3am, troops from the local Royal Field Artillery at Biscot arrived to support the police and the crowd dispersed.

Keep tabs on the past: sign up for our email alerts

Follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians

1 comment

Comment by John Harvey posted on

In the late 1980s I was a property lawyer working for the owner of the Luton Arndale Centre. It was my lot to get its title registered. Many of the deeds still bore the marks of the conflagration.