‘Il y a du nouveau’

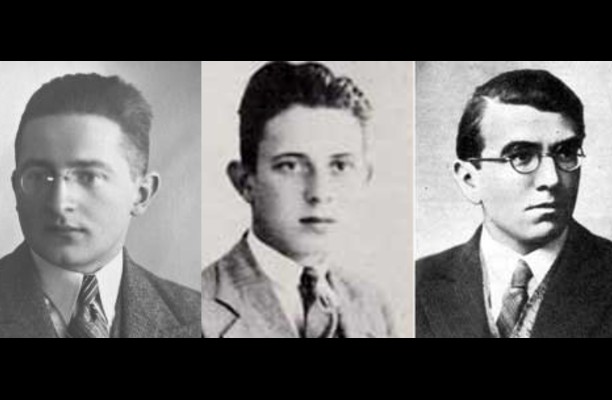

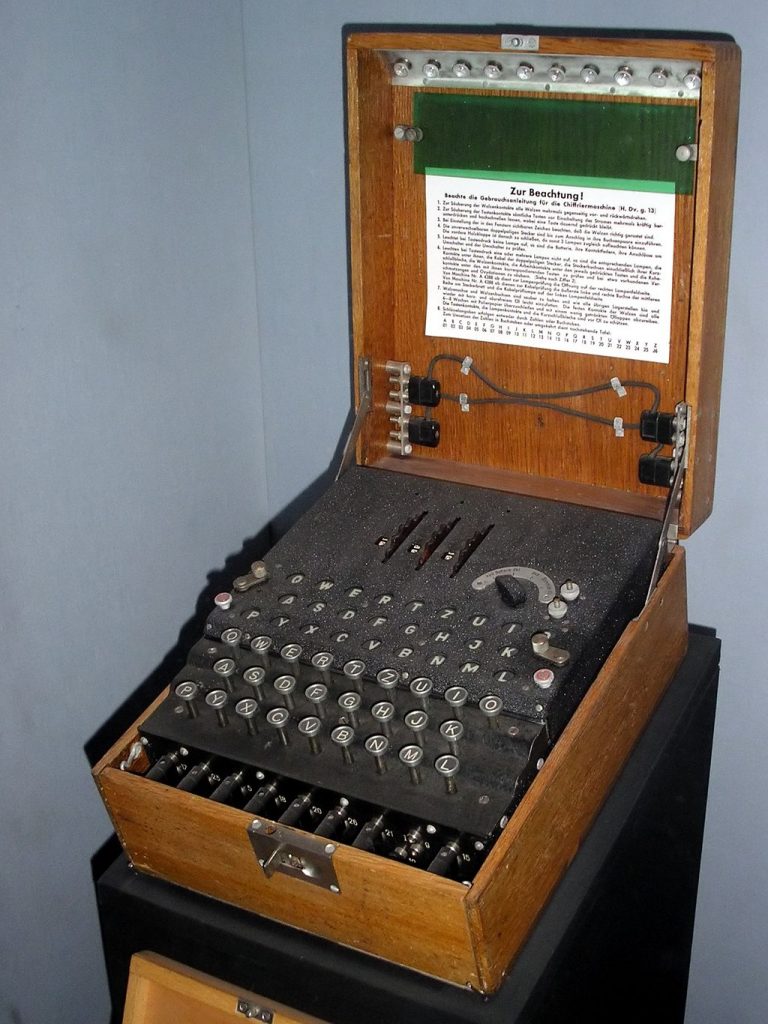

On 26 July 1939, in the Pyry Forest south of Warsaw, Polish cryptologists revealed to their British and French counterparts that they had been reading German signals traffic, transmitted by Enigma machines, since 1933. At a previous meeting in January, they had been reticent: but since then the threat from Nazi Germany had increased greatly. Hitler’s takeover of Czechoslovakia in March led to a British guarantee to come to Poland’s aid if attacked. But as SS troops flooded Danzig and German forces massed on the borders, the Polish General Staff were keen to tighten the links with Britain and France.

The head of the Polish Signals Bureau sent a coded message to his French counterpart on 30 June that ‘there is a new development’. This was not a cryptologic breakthrough, but a willingness to reveal the secret of the Enigma wiring sequence. Bletchley Park’s ‘Dilly’ Knox, while furious that the solution was one he had rejected, realised the importance of the Polish achievement, which shortened the British attack on Enigma by at least a year.[1] At this time MI5 and the Secret Intelligence Service (named MI6 to sound more military as war approached) were struggling to expand operations with scarce resources. This made the Government Code & Cypher School’s achievement particularly valuable.

‘Fire escapes and fire extinguishers’

Poland was not the only country looking for supportive friends in July 1939. Britain and France, alarmed by the increasing closeness and strength of the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo Axis, were trying to reach agreement with Turkey on co-operation in the event of hostilities in the Mediterranean. Istanbul, however, was hedging its bets in order not to alienate Berlin or Moscow. Italian claims of an imminent alliance with Spain, where Franco’s nationalist forces were now in control, increased the alarm felt in London and Paris.

During June and July, Anglo-French talks in Moscow aimed at securing a common front with the Soviet Union against Axis aggression progressed slowly. They were spun out by Foreign Minister Molotov who was adept in securing concessions (seeking a free hand in the Baltics) while giving none. William Strang, sent out by the Foreign Office to help, wrote that the negotiations with Moscow were

a humiliating experience. Time after time we have taken up a position, and a week later we have abandoned it... our need for an agreement is more immediate than theirs.

Berlin claimed the Moscow talks threatened the ‘encirclement’ of Germany. In vain the British Ambassador in Istanbul argued that

what we were doing was to supply our house with fire escapes and fire extinguishers... it would be ludicrous to interpret this as a sign that we intended to set fire to it.

German protests were cynically disingenuous, as Anglo-French hopes of a successful conclusion to their Moscow talks were dashed by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact a few weeks later.[2]

‘The reality of the new Great Germany has got to be understood and faced’

Sir Nevile Henderson, British Ambassador in Berlin, wrote these words while expressing some admiration for Hitler’s ‘abounding faith in his own mission’, and hoping war might be averted.[3] Though his faith was not shared in Whitehall, Chamberlain’s government was not quite ready, in late July 1939, to accept that war was inevitable.

But the desperate efforts to reach agreement with potential allies show how close the prospect appeared. Britain could not rely on the support of the United States, where President Roosevelt, though shocked by Hitler’s march into Prague, struggled to get Congressional approval for the amendment of isolationist legislation.

The military party in Japan accused Britain of supporting China in the Sino-Japanese war (treating Britain, as the Ambassador in Rome complained, ‘as if we were a second-class Power’). There were even difficulties with Poland, which Chamberlain had pledged to defend, in negotiating a financial agreement.

The editor of Documents on British Foreign Policy, Sir E.L. Woodward, wrote in the preface to the volume documenting this period: ‘The choice between peace and war lay with Germany.’

To the cryptologists who met in the Pyry forest on 26 July 1939, that fact was abundantly clear. Their collaboration heralded ‘the most consequential intelligence-sharing arrangement of World War Two’.[4]

[1] Dermot Turing, X, Y & Z: The real story of how Enigma was broken (London: The History Press, 2018); see also Stephen Budiansky, Battle of Wits: The complete story of codebreaking in World War II (London: Viking, 2000).

[2] Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1939, Third Series, Vol. VI, Nos. 376, 399, 427 and passim.

[3] Ibid., No. 460.

[4] Turing, op. cit., p. 114.

Keep tabs on the past: sign up for our email alerts

Follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians