'Knowing the English and the traditions of British foreign policy, I could not accept that Chamberlain would make any firm commitments in Eastern Europe’.

Ivan Maisky, Soviet Ambassador in London[i]

On 31 March 1939, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain told the House of Commons that ‘in the event of any action which clearly threatened Polish independence, and which the Polish Government accordingly considered it vital to resist, His Majesty’s Government would feel themselves bound at once to lend the Polish Government all support in their power.’[ii] The French Government endorsed this pledge.

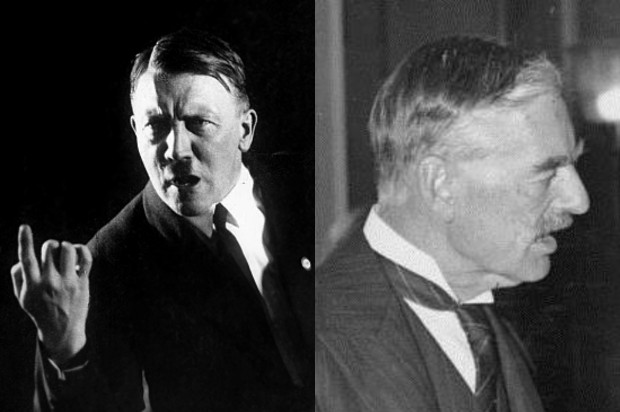

This guarantee was to lead Britain to declare war on Nazi Germany 6 months later. It was welcomed by those who thought Chamberlain had waited too long to challenge Hitler’s aggression in Europe, and surprised those who had not expected him to deviate from his insistence that the appeasement of Europe remained a realistic goal. Only 2 weeks earlier Chamberlain pronounced the international outlook ‘serene’, Anglo-German trade talks were planned, and his response to Hitler’s takeover of Czechoslovakia on 15 March was one of sorrow more than anger. Why now pledge the British government to defend Poland, an Eastern European country vulnerable on all its borders?

Where will Hitler strike next?

The key to the Polish guarantee was the fact that the French would fight for Poland, as they would not fight for Czechoslovakia. The Chiefs of Staff told Chamberlain that if Britain had to fight Germany, it was better to do it in alliance with Poland and France. The French were willing to have meaningful staff talks and there was close intelligence liaison, although they were sceptical about imminent German aggression in the West.[iii]

Secret reports received in London in late March indicated Hitler planned to move against Poland, but they were treated with caution, in view of an embarrassing false warning passed on to Washington in January.[iv] Yet rumours abounded:

- Hitler was about to attack Holland, or Romania

- Italy was about to invade Albania (as it did in April), or demand colonial concessions from France

- the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo axis was about to become a firm military alliance, that Franco might join; Germany sought Polish help in an attack on the Soviet Union

The US State Department believed Germany would mobilise on the Dutch frontier and demand the cession of the Netherlands East Indies.

By late March, it was clear that Hitler was poised to attack–somewhere. But as the Military Attaché in Berlin wrote, ‘the great difficulty–even to skilled observers–is to decide when “normal abnormality” merges into something more significant.’[v]

Two fighting fronts, 3 armed services and the fourth arm of defence

Since 1934, British rearmament had been predicated on long-term deterrence rather than imminent conflict, based on the Treasury doctrine that economic stability was the fourth arm of defence. By February 1939 this had changed: Hitler’s aggression, the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo axis, Nationalist victory in the Spanish Civil War and the uncertainties of American and Russian policies meant that ‘military strategy was determining economic policy rather than the other way round’.[vi] All 3 armed services were competing for resources and equipment, scrambling to match (exaggerated) estimates of German military might.

The one thing the Chiefs of Staff agreed was that Britain would struggle to fight on more than one front at once. But Chamberlain’s attempts to secure the Mediterranean foundered on Mussolini’s ambitions, and British interests in the Far East were threatened by Japanese plans for a Pan-Asian ‘new order’, while the USA urged support for the beleaguered Chinese nationalists in the bitter Sino-Japanese conflict.

The military challenges were diverse and demanding. 20,000 British troops were pinned down in peacekeeping operations in Palestine, while Chamberlain’s resolution, however, was confirmed by domestic, as well as international considerations.

Anderson Shelters and Anti-semitism

The public mood in Britain had changed since Chamberlain returned from Munich in September 1938 announcing ‘peace for our time’.[vii] Hitler’s increasingly intemperate outbursts, brutal measures against Jews, and aggressive treatment of Czechoslovakia seemed to even the most inward-looking citizens to be harbingers of war. To those on the Left, the British government’s recognition of the Franco regime in February 1939 appeared a bitter betrayal of the Republican cause, as well as appeasing a pro-Nazi dictator.

The League of Nations had proved powerless, and when German forces moved into Czechoslovakia on 15 March, it seemed clear Hitler was determined to dominate Europe. Many people now favoured rapid rearmament, anti-air raid precautions and the building of shelters for which Sir John Anderson had ordered 120,000 tons of steel sheets. They no longer believed Chamberlain when he spoke of peace, and wanted concrete preparations for war. The Prime Minister recognised this.

Time to call ‘Halt!’

For Sir Alexander Cadogan, FO Permanent Under-Secretary, by 20 March 1939 Chamberlain had ‘reached the cross-roads’. Poland ‘set up a signpost’ for the Prime Minister, despite his desire for peace, his reluctance to trust the Russians and doubts about American willingness to abandon neutrality. Giving a public guarantee would end the ‘agonising doubts and indecisions’ that had beset him in his efforts to secure the appeasement of Europe. ‘The die is now cast and Hitler may bomb us. But I think we’ve done right.’[viii]

- if you are interested in our work then feel free to read our blogs on GOV.UK

- keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts

- follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians

[i] Diary entry by Ivan Maisky, Soviet Ambassador in London, 29 March 1939 (Gabriel Gorodetsky (ed), The Maisky Diaries (London: Yale, 2015).

[ii] Parl. Debs, 5th ser., House of Commons, vol. 345, col. 2415.

[iii] See Paris telegram 1387 to the Foreign Office, 30 March 1939, printed in Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1939 (DBFP), Third Series, Vol. IV, No. 574; and Keith Jeffery, MI6 (London; Bloomsbury, 2010). Pp. 291-2.

[iv] See ‘SIS on the eve of War, 1939’, in FCO Historians, The Records of the Permanent Under-Secretary’s Department, March 2005, ihttps://issuu.com/fcohistorians/docs/therecordsofthepermanentundersecret

[v] Berlin telegram 72 to the FO, 28 February 1939, printed in DBFP, ibid, No. 160.

[vi] G.C. Peden, Arms, Economics and British Strategy (Cambridge; Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 172.

[vii] https://history.blog.gov.uk/2013/09/30/whats-the-context-30-september-1938-the-munich-agreement/

[viii] David Dilks (ed), The Diaries of Sir Alexander Cadogan 193801945 (London: Cassell, 1971), entries for 20, 30 and 31 March 1939.