The American Congress and the American people have never accepted any literal principle of equal sacrifice, financial or otherwise, between all the allied participants. Indeed, have we ourselves?

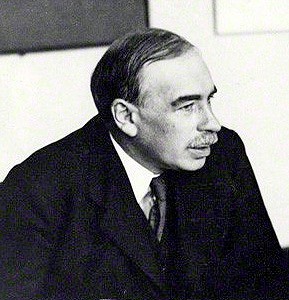

Lord Keynes, defending the Agreement in the House of Lords, 18 December 1945.

Seventy five years ago, an agreement was signed in Washington for a US loan to the UK government of $3.75 billion repayable over 50 years.[1] The UK’s final payments on this, and a loan from Canada agreed in March 1946, would not be made until December 2006.

Though the terms of the US loan were not ungenerous, the British government found them hard to swallow. Nevertheless, in December 1945 most people in the government thought the agreement an essential lifeline. Some ministers and officials opposed it, with its attached conditions requiring radical changes to UK commercial arrangements. Others favoured refusal, confident the US would improve its offer if the UK held out long enough.

But for Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, who successfully urged the Cabinet to agree to the deal, the main arguments were geopolitical as much as financial. In his view, the agreement was essential to emphasise Britain’s key position as a bridge between East and West, to revive trade with Europe, and above all to keep on close terms with the US. The Anglo-American Financial Agreement must be seen in that wider context.

The end of the ‘Big Three’

The end of the Second World War in August 1945 brought not just peace but profound global shock. The victorious Grand Alliance dissolved, leaving 2 Superpowers ‒ USA and USSR ‒ with a bankrupt and exhausted UK in third place. The ideological gulf between Soviet communism and American capitalist democracy, sublimated during wartime alliance, now threatened an already unstable international situation. The atomic bomb, employed to devastating effect against Japan, cast a global shadow.

In some territories, like Greece or mainland China, internal conflict raged. In others, anti-colonial sentiment gathered pace. In mainland Europe, including the defeated and divided Germany, large numbers of refugees and displaced persons exacerbated widespread shortages of food, fuel and shelter.

The new ‘world organisation’, the United Nations, was planned but not up and running. Peacemaking machinery, including the new Council of Foreign Ministers, soon exposed dangerous cracks in international cooperation. The world was being reshaped, not just by conquest and physical devastation, but by shifting balances of economic power and political rivalry.

The Financial Agreement was negotiated against this backdrop between September and December 1945.

Seeking justice and finding temptation

The US decision to cut off wartime Lend-Lease arrangements abruptly after VJ-Day in August 1945 was a shock to Britain’s newly elected Labour government, committed to a massive and expensive programme of domestic legislation. Abroad, it faced heavy and underfunded global commitments, including providing food for colonial territories, coal to liberated Europe and responsibility for the British zone in Germany (plus a vast machinery of military government).

The economist JM Keynes, who had been warning of a ‘Financial Dunkirk’ since March 1945, led the negotiating team to Washington in early September. Keynes and his team were seeking a grant in aid or at least an interest-free loan, seen as ‘justice’ in recompense for Britain’s wartime sacrifices.

It soon became clear that only a commercial arrangement — the ‘temptation’ of borrowing with interest — was on offer. What is more, the Americans sought ‘sweeteners’ for the loan, including extended leases on military bases in British territory and preferential access for US corporations to civil aviation routes and telecommunications networks. The United States was emerging enriched and industrially powerful from war. The US desire to leave the rest of the world to sort out their own problems was matched by ambitious plans for economic expansion and the attractions of exerting political leadership.

Though there was much goodwill towards the UK, US negotiators harboured a perennial suspicion that the British were trying to outsmart them. They distrusted Attlee’s socialist government. In return for financial help Britain must abandon imperial preference, make sterling convertible, and effectively accept client status.

The suspicions of Josef Stalin

Bevin understood the need for concessions to the US, and was convinced that strong Anglo-American ties trumped most objections. But he was worried that US determination was to control atomic secrets and raw materials, and to conclude security arrangements before the UN Security Council had even met. He thought this would give the Russians ‘gratuitous and justifiable cause for suspicion’.[2] He was right.

The Soviet Union had expended enormous economic and human resource in pursuit of Allied victory. Its determination to secure acknowledgement of, and recompense for, the scale of its sacrifice was underpinned by deep suspicion that the USSR would be frozen out of postwar spoils and atomic know-how. The extensive Soviet espionage machinery in the UK and US, partly exposed by the defection of Gouzenko in Canada in September,[3] confirmed Stalin’s suspicions and coloured Soviet diplomatic tactics.

In these first postwar months, hopes of continuing east-west cooperation were not dead but were fading, with each side blaming the other. If there were trouble ahead, Britain was on the side of the US, as their increasingly close intelligence relationship showed. The Financial Agreement tightened the bond.

Commenting on the Financial Agreement, Keynes told the House of Lords that "Our American friends were interested not in our wounds... but in our convalescence. They wanted... to be told that we intended to walk without bandages as soon as possible." In fact, a great deal more help would be needed from the US, not just for Britain but for Western Europe as well. The Financial Agreement of December 1945 was an early indicator of American commitment to European postwar reconstruction.

[1] For the Agreement, and British documentation on the negotiations that led up to it, see Documents on British Policy Overseas (DBPO), Series I, Vol. III. A detailed account can also be found in Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes, vol. 3, Fighting for Britain 1937-1946, Chapter 12.

[2] Memo by Bevin, 29 November 1945, printed DBPO, Series I, Vol. III, No. 135.

[3] On the defection, which revealed details of Soviet spy networks in Canada and the US, and the existence of a British atomic spy, Alan Nunn May, see ‘The CORBY case: the defection of Igor Gouzenko, September 1945’, in From World War to Cold War: Records of the Foreign Office Permanent Under-Secretary's Department, 1939-51; also documentation in FCDO Historians, Britain and the making of the postwar world: the Potsdam Conference and Beyond.

1 comment

Comment by Ken Nannichi posted on

I’ve just finished reading Benn Steil’s “The Battle of Bretton Woods”. It portrayed US-UK financial confrontations, not collaborations in face of Soviet Union, in the process towards, and afterwards, the December 1945 agreement. Worth reading.