The Downing Street Policy Unit[i] has been part of the inner workings of British government for half a century. It was created by Prime Minister Harold Wilson in March 1974.[ii] All successive prime ministers have retained the Policy Unit, adapting it to fit the needs of their government.

But why does a prime minister need a Policy Unit?

Unlike secretaries of state, a prime minister does not have a formal department. The machinery of government to support them is small in terms of staff numbers, compared to many government departments. Indeed, during Wilson’s first premiership (1964-70) he recognised the issue of ‘the hole in the centre’, as did his successor Edward Heath (1970-74).[iii] With the creation of the welfare state as well as technological and societal change, the role of the prime minister and functions of government had grown and become more complex. The “hidden wiring”[iv] of government however had not caught up. The advent of a Policy Unit was therefore significant in bolstering a prime minister’s ability to access alternative policy advice, which was responsive to the urgent and the important issues of the day, as well as politically attuned.

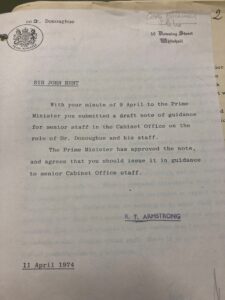

In establishing the Policy Unit, Wilson was partially implementing a recommendation of the Fulton Report on the Civil Service (1968) to introduce Planning Units.[v] Wilson intended for his Unit to act as a new source of politically aligned policy analysis on short to medium term issues.[vi] This would complement and counterbalance the politically impartial policy advice provided by the Civil Service. The first head of the Policy Unit, academic Bernard Donoughue, retells the story of Wilson asking him to take on this new role. The Prime Minister was clear about the tasks and objectives; he wanted the new Unit to be his ‘eyes and ears in Whitehall’. [vii] Donoughue set about staffing the Unit with external recruits from outside of the Civil Service, including from academia.[viii]

Wilson’s Policy Unit was part of a larger whole of alternative policy provision. It sat alongside an innovation created in 1970[ix] by Wilson’s predecessor Heath, to act as a “Think Tank” of sorts – the Central Policy Review Staff (CPRS). As ever, the geography of power had a part to play in the influence of central units. The Policy Unit provided short to medium term policy analysis to the Prime Minister from within No.10. Whereas the CPRS offered longer-term policy advice to the Prime Minister and ministers from next door in the Cabinet Office. Wilson’s biographer Ben Pimlott reflected that ‘Wilson was happiest when he felt that advice was reaching him from different angles.’[x] But as Wilson’s period in office looked to be ending, Donoughue wrote in his diary, ‘I wonder what will happen to the Policy Unit.’[xi] As it was, Wilson’s successor James Callaghan kept the Policy Unit. But how would it fair under a government of a different political hue?

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (1979-90) made use of the Policy Unit throughout her premiership. A note written on 9 May 1979, by civil servant Kenneth Stowe, the Principal Private Secretary to the Prime Minister, outlined the intended purpose of the Policy Unit under the new government. The Unit would have the task of assisting the Prime Minister in ‘developing and maintaining the strategic policies of the Government, with a view to achieving its long-term objectives.’[xii] Under Thatcher, the Policy Unit acted as ‘a kind of special forces little platoon, on economic and industrial issues.’[xiii] It grew into a group of experts who shadowed a selection of key policy areas in Whitehall departments. There were several heads of the Policy Unit during Thatcher’s long tenure including businessman, John Hoskyns; journalist and novelist, Ferdinand Mount; merchant banker turned politician, John Redwood; and finally academic and economist, Brian Griffiths. When in 1983 Thatcher disbanded the Central Policy Review Staff, some of the CPRS staff joined the Policy Unit.[xiv] Then Policy Unit member David Willetts, recorded seven functions of the Unit under Thatcher:

- ‘A small creative think tank’;

- Policy advice on papers from departments put to the Prime Minister;

- Reports on progress of policy development;

- Considers issues less likely to be raised by inter-departmental machinery;

- Fosters good relations between departments and No.10 to focus on critical issues;

- Offers a ‘non-Whitehall’ policy perspective to the Prime Minister;

- Acts as a ‘grand suggestions box’ for the Prime Minister, drawing on ideas from universities and within the Civil Service.[xv]

Thatcher herself reflected that ‘the value of the Unit […] lies in its flexibility and involvement in day-to-day policy matters, on the basis of close collaboration with the Prime Minister.’[xvi]

The Policy Unit under Prime Minister John Major (1990-97) was first headed by Sarah Hogg, an economic journalist. In becoming head, Hogg was the first woman to hold the role. She was an influential and close adviser to Major. During her tenure, the Unit provided policy advice on the economy, Europe and social policy.[xvii] Major described her as someone ‘respected by Civil Service mandarins and by politicians – a double not easily achieved.’ [xviii] For Hogg, the function of the Policy Unit under Major was ‘to keep the Prime Minister in touch with outside thinking, to work on his own ideas to act as a sounding board for ministers, advising on the flow of proposals and counter-proposals that pour in continuously from all around Whitehall.’[xix] In practice, Hogg said the Policy Unit tried to provide both ‘grit and oil in the government machine.’[xx] Hogg was succeeded by management consultant, Norman Blackwell. Like his predecessors, Major found the Policy Unit to be a valuable source of brain power for developing his domestic policy objectives.[xxi]

As Prime Minister (1997-2007) Tony Blair, retained the Policy Unit as well as introducing several new units at the centre of government. The first head of Blair’s Policy Unit was David Miliband, who had been a policy analyst at a think tank. An existing member of the Unit, Andrew Adonis, took over in 2001 as head of policy. At this point, the Blair government experimented with merging the Policy Unit and the Prime Minister’s Private Office to form the Policy Directorate. The Policy Directorate was to focus on day-to-day priorities and short-term policy advice. The Prime Minister’s Principal Private Secretary, Jeremy Heywood, led the Policy Directorate. This change was intended to promote further cohesion in No.10, yet the longstanding functions of the Policy Unit and Private Office continued. Adonis was succeeded by Geoff Mulgan, an established key figure in the Blair government who was then also leading the Strategy Unit. Prime Minister Blair’s final head of policy (and strategy) was management consultant, David Bennett. Blair reflected on his motives for machinery of government changes at the centre, ‘In Downing Street, I formed a Delivery Unit, Policy Unit and Strategy Unit, staffed largely by outsiders and charged specifically with trying to learn the lessons of change.’[xxii] These units played an important role in developing and implementing the Blair government’s ambitious public service reform agenda.

Over the last 50 years, the Policy Unit has proved to be a crucial part of the machinery of government for prime ministers. It has been staffed at times by politically-appointed special advisers only, at other times a mix of special advisers and civil servants, and on occasion by civil servants exclusively. Harold Wilson’s innovation, created half a century ago, has endured because it has been sufficiently elastic. It has evolved and allowed the prime minister of the day to adjust it to their governing style and their vision for the country.

Dr Michelle Clement is Lecturer and researcher on government reform and delivery at The Strand Group, King’s College London where she teaches on the MA Government Studies. She is also Researcher in Residence at No.10 Downing Street.

@MLClem @TheStrandGroup

[i] Also referred to as the No.10 Policy Unit.

[ii] Harold Wilson was Prime Minister 1964-1970 and 1974-1976.

[iii] ‘The hole in the centre’ is attributed to Cabinet Secretary, John Hunt (1973-79) and quoted in, J. Davis, Prime Ministers and Whitehall 1960-74 (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007), p. 117 and 149.

[iv] P. Hennessy, The Hidden Wiring: Unearthing the British Constitution (London: Indigo, 1996).

[v] P. Hennessy, Whitehall (London: Pimlico, 2001), p. 203.

[vi] P. Hennessy, The Prime Minister: The Office and Its Holders since 1945 (London: Penguin, 2000), p. 359.

[vii] B. Donoughue, The Heat of the Kitchen (London: Politico’s, 2003), p. 117.

[viii] D. Kavanagh and A. Seldon, The Powers behind the Prime Minister: The Hidden Influence of Number Ten (Kindle edition, London: HarperCollins, 2013), Location 2221.

[ix] The CPRS officially went live in February 1971. See, Davis (2007), p. 117.

[x] B. Pimlott, Harold Wilson (London: HarperCollins, 1993), p. 620.

[xi] B. Donoughue, Downing Street Diary with Harold Wilson in No.10 (London: Jonathan Cape, 2005), p. 471.

[xii] Kenneth Stowe minute for Margaret Thatcher, Thatcher Papers, Churchill Archives Centre, THCR 2/6/2/125. Available here: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/112172

[xiii] Hennessy (2000), p. 409.

[xiv] K. Jenkins, Politicians and Public Services: Implementing Change in a Clash of Cultures (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2008), p. 51.

[xv] Hennessy (2001), pp. 659-660.

[xvi] M. Thatcher, The Downing Street Years (London: HarperCollins, 1995), p. 31.

[xvii] Hennessy (2000), p. 447.

[xviii] J. Major, John Major: The Autobiography (London: HarperCollins, 1999), p. 211.

[xix] S. Hogg and J. Hill, Too Close to Call: Power and Politics – John Major in No.10 (London: Little, Brown, 1995), p. 24.

[xx] Hogg and Hill (1995), p. 24.

[xxi] Major (1999), p. 261.

[xxii] T. Blair, A Journey (Kindle edition, London: Cornerstone, 2010), Location 377.