Clement Attlee bore little resemblance to the contemporary politician. He had no time for the things that are now the stock-in-trade of all serious aspirants for high office: image and public relations. Attlee was so apparently unconcerned with presentation that when a reporter asked him whether he would like to make a comment on Labour’s general election campaign, then in full flow, he simply said ‘No’.

It is difficult to envisage a twenty-first century politician passing up the opportunity to promote their ‘message’. Even privately, ministerial colleagues found Attlee difficult to engage with; one of the few things he was willing to actually talk about was cricket.

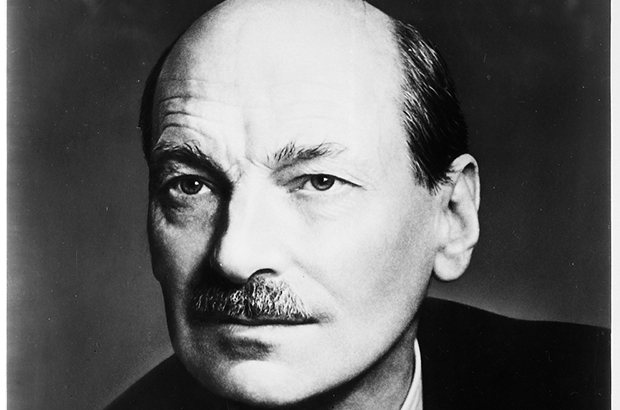

That was always the way with Attlee. Yet his quiet persona, reserved demeanour and lack of charisma concealed something equally striking: formidable political skills. These had made Attlee one of the political giants of the modern age, every bit the equal of Baldwin, Churchill and Thatcher. He was underestimated throughout his career – and those who did so usually paid a high price for the mistake. Born to an upper-middle class background and drawn into the Labour Party through social work in poor areas of London, Attlee became Prime Minister in 1945 and oversaw a programme of radical, if often controversial, economic and social legislation. It is this for which he is most remembered.

A formidable Deputy Prime Minister

But it is often forgotten that Attlee had already come to occupy a powerful place in Westminster, as Deputy Prime Minister to Churchill during the cross-party coalition formed in 1940 to fight the Second World War. Nobody did more to hold together the tense alliance between the Conservatives and Labour. Attlee also ran large policy areas of the home front while Churchill focused on the military struggle, occupying a position akin to a spider nestled at the centre of the vast Whitehall web. Few were more adept at manipulating the committee system that was created between 1940 and 1941 to mobilise Britain’s resources. Attlee pushed Churchill to establish a new body, the Lord President’s Committee, as an informal Cabinet for domestic issues and helped to make it the core of the Whitehall machine.

Attlee was an extremely powerful, and effective, Deputy Prime Minister. It was in this role that Attlee deployed his skills at the highest level for the first time. Until his retirement, very few could best him in a committee room. His abilities as a chairman were astonishing. Attlee was able to cut to the heart of a matter, helping other ministers to devise creative solutions to difficult challenges. He did not allow others to talk for too long and was usually able to steer meetings to his desired end. His pipe was also a useful political prop; when in a difficult spot, lighting it and taking a puff would buy time to think. As a political manager, Attlee had few equals. He was equally good at managing the Labour Party. His sure touch enabled him to deflect rivals – often by giving them difficult jobs. This may have been why Attlee was the longest serving leader of a major British political party during the whole century, guiding Labour for two decades between 1935 and 1955.

Extending the role of the state

Attlee became Prime Minister when Labour won the 1945 election. He fended off an attempt by his great rival Herbert Morrison, grandfather of Peter Mandelson, to seize the premiership before Attlee could see the king and accept the commission to form a government. Attlee implemented one of the most ambitious legislative programmes in British history, creating the National Health Service, expanding the size and scope of the welfare state and taking major sectors of the nation’s industry into public ownership. The Attlee government even sought to control the supply and prices of some commodities in order to ‘plan’ the economy. The Labour Party had, of course, been committed since its inception to creating a more egalitarian society through state action, particularly intervention in the economy. During the war a civil servant, William Beveridge, had drawn up a blueprint for a future welfare state that captured the imagination of the public and convinced Labour to make this one of its priorities.

The economic legacy of the Attlee government endured in its essentials until the election of Mrs. Thatcher in 1979. Attlee’s social and welfare policy continues to form a major part of the political landscape of the twenty-first century. Attlee was an active and energetic Prime Minister, especially between 1945 and 1947. But his record is polarising. Partly that comes down to subjective political preferences. Yet objective judgements are also difficult to make, because the government was confronted with the unprecedented economic disarray and dislocation that followed the Second World War. Faced by what John Maynard Keynes called a ‘financial Dunkirk’, Attlee’s government was forced to impose stricter rationing in peacetime than had existed during the war. Serious financial crises in 1947 and 1949 damaged the Labour government. The middle-classes who had voted in droves for Labour in 1945 abandoned the party at the general elections of 1950 and 1951, as years of poor living standards took their toll. In hindsight it seems that Attlee’s government may have been over-ambitious; restoring prosperity at the same time as financing expanded social provision was probably trying to achieve too much, too quickly.

Important role in the Cold War

Internationally, Attlee afforded his Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, the freedom necessary to maximise Britain’s reduced global standing; the Labour government recognised the ambitions of the USSR and was an important architect of the Atlantic alliance with the United States. This helped to address Britain’s geopolitical dilemmas when the country was too weak to do so itself. Attlee’s government was an important force in the febrile international atmosphere of the early Cold War. During this time Britain also began the retreat from empire, but it should not be forgotten that the withdrawals from India and Palestine left much bloodshed in their wake.

Attlee finally retired in 1955, and died 12 years later. Historians have struggled to understand him – just as his contemporaries did. It is often difficult to detect his fingerprints in the surviving sources. Never a great gossip, Attlee revealed little of himself and his plans to those around him, and thus he remained a deeply enigmatic figure. He suggested that the key to being a successful Prime Minister was ‘a sense of urgency, of dispatch … you must have a sense of timing, judgement of what will go and what won’t and when’. Few politicians have matched his command of those skills.

Further reading

Francis Beckett, Clem Attlee (London, 1997).

Robert Crowcroft, Attlee’s War: World War II and the Making of a Labour Leader (London, 2011).

Kenneth Harris, Attlee (London, 1982).

Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour in Power, 1945-1951 (Oxford, 1984).

Copyright Robert Crowcroft. This article was produced as part of the No10 Guest Historian series, coordinated by History & Policy.

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for email updates from this blog.

5 comments

Comment by Bryn Davies posted on

Labour received more votes in 1950 and 1951 than it did in 1945, contrary to what is suggested above.

Comment by Joseph Bailey posted on

It would be interesting to be told more about Atlee's attitude towards the great upheaveals in the Labour party in the 1930s.Towards Ramsay MacDonalds decision to join the Tories in the National Government and the fall of George Lansbury.Very little has discussed about Atlee's political movements at this time, preferring instead to concentrate on his Finest Hour in the founding of the Welfare State after 1945

Comment by Debera Willis posted on

A recent television series called The Crown indicates that Atlee was actually a drug addict is that true?

Comment by Tpup posted on

Debera Willis you are talking about Anthony Eden who was prescribed a lot of drugs after his gall bladder surgery and the drugs had a ton of bad side effects.

Comment by Nick posted on

It's pretty clear in the series that those drugs he was prescribed were narcotics. The side effects being euphoria, pain relief and drowsiness. Can't seem to find anything in the literature about this but then again this was probably common practice back then for an ulcer.