Sunday 28 June 1914 was warm and sunny, and most Londoners were enjoying a day of rest. One exception was the resident clerk at the Foreign Office who was on duty to deal with any unexpected crisis that might occur. At 4pm in the afternoon a short telegram arrived from the Consul General in Sarajevo: ‘News received here heir apparent and his consort assassinated this morning by means of an explosive nature’.

Two hours later further detail arrived from the British ambassador in Vienna: ‘Bomb was first thrown at their carriage on their way to town hall and later young Serbian student shot them both with a revolver as they were returning to Konak’.

Thus began the ‘July Crisis’—as the period between the assassination in Sarajevo of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the outbreak of the First World War became known. By the following morning news of the murder of the heir to the Habsburg throne, and his wife Sophie Chotek, was widespread. Under the headline ‘The Austrian Tragedy’, The Times devoted extensive coverage to the event. But although the assassination shocked Europe few initially expected the tragedy to have serious political consequences outside the Balkans. Yet within 37 days Europe was convulsed by conflict and Britain found herself embroiled in a world war.

Follow the July crisis on Twitter

100 years on from the July Crisis of 1914 the Foreign & Commonwealth Office are tweeting, in real time, extracts from Foreign Office telegrams, dispatches and letters to give a feel for how the sequence of events unfolded and how the crisis was viewed from Britain.

The title draws on the immortal words of the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey: ‘The lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.’

Keep track of developments by following @WW1FO on Twitter

Diplomatic traffic

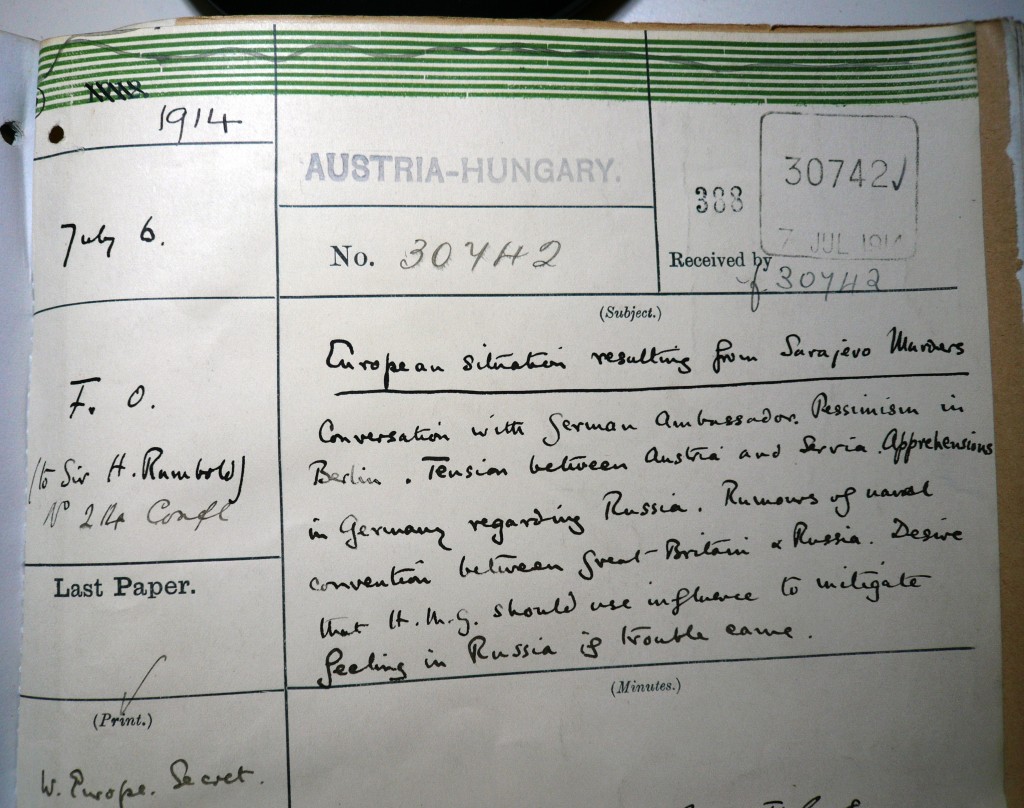

The tweets are drawn from a volume of British diplomatic documents, first published in 1926, which captured the unravelling of events during the July Crisis: British Documents on the Origins of the War, 1898-1914 Volume XI: The Outbreak of War, 28 June – 4 August 1914.

They feature diplomatic correspondence and minutes from the main players in the July Crisis: Sir Edward Grey; Sir Arthur Nicolson, Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office; Sir Eyre Crowe, Assistant Under Secretary of State at the Foreign Office; Sir Francis Bertie, British Ambassador in Paris; Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador in St. Petersburg; Sir Maurice de Bunsen, British Ambassador in Vienna; Sir Edward Goschen, British Ambassador in Berlin; Sir Francis Villiers, British Minister in Brussels; Dayrell Crackanthorpe, British Chargé d’Affaires in Belgrade; W.G. Max Müller; British Consul-General in Budapest and J.F. Jones, British Vice-Consul in Sarajevo.

In their despatches ambassadors recount meetings with government officials, conversations with diplomats from other countries and summarise what the national press were saying. Incoming despatches were circulated around the Foreign Office where officials often made comments on them, known as ‘Minutes’.

The Foreign Secretary wrote to ambassadors issuing instructions or reporting on conversations held with foreign envoys in London. During his period as Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey went abroad only once and preferred instead to conduct relations through ambassadors in London: Count Lichnowsky for Germany, Count Benckendorff for Russia, M. Cambon for France and Count Mensdorff for Austria-Hungary.

The Permanent Under-Secretary of the Foreign Office corresponded privately with diplomats, especially those in more remote posts, to keep them in touch with thoughts and opinion at home, and pass on information from other Missions.

For incoming communications the tweets are arranged in order of the date on which they were received in the Foreign Office, not despatched from posts abroad. Modern spellings of place-names and people have been used. All of the documents can be read in full in this (third-party) copy of the volume.

Origins of the July Crisis

Although the assassination of the Archduke provided the immediate catalyst for war, its origins stretched back to great power rivalries of the 19th century: the humiliating defeat of France by Prussia in War of 1870 and the resulting loss of Alsace-Lorraine, the competition between Austria-Hungary and Russia for influence in the Balkans, Germany’s bid for world power status and subsequent naval rivalry with Britain.

By 1914 Europe was divided into two rival camps, each with millions of men under arms, and each with its own enmities and fears. On the one hand stood the Triple Alliance comprising Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy; on the other the Dual Alliance of France and Russia. Britain was linked to the latter through ententes (or understandings) concluded with France in 1904 and Russia in 1907—commonly referred to as the Triple Entente. But Britain sought not just to support France and Russia against German hegemony but also to prevent them from being drawn into the German orbit or allowing them to feel they could rely on British support to challenge Germany themselves: in essence to maintain a ‘balance of power’ in Europe.

Germany tried to split the Anglo-French entente by provoking diplomatic crisis over Morocco in 1905 and again in 1911. However this had the effect of confirming, rather than undermining, Anglo-French friendship: both countries entered into ostensibly non-committal military conversations to plan how best they might cooperate if a war broke out and also concluded a Naval Agreement in 1912 under which the French fleet guarded the Mediterranean and the Royal Navy guarded the north French coast.

Attempts to reach a political and naval settlement with Germany failed as both countries had irreconcilably different goals. Germany wanted to secure British neutrality in the event of a European war while Britain wanted an end to the naval race with Germany. However better relations with Germany were achieved over minor points. In August 1913 an agreement was reached over the future of the Portuguese colonies and in June 1914 Britain agreed to join in the Baghdad railway scheme.

As Turkish power continued to fade in Europe wars broke out over her territorial possessions. Firstly, in 1912 Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria and Montenegro fought the Ottomans for their Balkan territory. The intervention of the larger European powers brought about an end to the conflict but in 1913 fighting again broke out, this time over the spoils.

Tensions in the region were still high in 1914. This unrest and nationalistic fervour was a concern to Austria-Hungary with her multinational empire. The Habsburgs had long worked to curb demands for Slav autonomy within their borders and they had an uneasy relationship with their neighbour, Serbia, one of the main beneficiaries of the Balkan Wars.

German leaders were pessimistic over the perception of encirclement by the Triple Entente and the resurgence of Russian power, since the latter’s defeat by Japan in 1905. Austria-Hungary worried about Serbia, as a champion of pan-Slavism, and Russia, both as a regional competitor and supporter of Slav nationalism.

It was against this backdrop of nationalism and militarism, alliances and rivalries that the July Crisis unfolded…

Look out for the tweets from @WW1FO starting on 28 June 2014.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.

1 comment

Comment by Dan posted on

What a great idea. Very clever!