The Battle for Berlin, April to May 1945

The image of the hoisting of the Red Flag over the Reichstag 2 May 1945 has come to represent the ‘total victory’ of Soviet Russia over Nazi Germany in the Second World War. That same day, General Helmuth Weidling, the last remaining commander of the Nazi forces defending the German capital, ordered ‘the immediate cessation of resistance’, thereby surrendering the city to the Red Army.

However, the iconic shot, taken by the famous Soviet war photographer Yevgeny Khaldei and published on 13 May 1945 in the Ogonyk magazine, was a stage-managed re-enactment. According to Soviet accounts, the real hoisting of the Red Flag atop the Reichstag occurred on the night of 30 April after repeated attempts by Soviet soldiers to overcome a determined German garrison. But this date must also be treated with caution. The Soviet command and soldiers were obsessed with capturing the Reichstag by 1 May in order to be able to mark victory on International Worker’s Day, whilst fierce fighting continued in Berlin and its outskirts for some days after. Nevertheless, it was undeniable that by the beginning of May the Red Army had conquered ‘the lair of the fascist beast’.

The Soviet capture of Berlin came at a heavy price: 78, 291 Red Army soldiers killed and 274,184 wounded. The outcome was never in doubt: 90,000 German defenders faced over a million Red Army soldiers. The Nazi forces defending Berlin consisted of depleted and poorly armed Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS divisions, poorly trained and unfit Volkssturm (the German people’s militia established in 1944-45, made up of the old and unfit) and members of the Hitler Youth. However, there was bitter street fighting. The fear of Russian reprisals spurred on by Nazi propaganda, especially amongst the foreign contingents of the SS, inspired a ferocious last stand. They calculated that it would be better to deal with the Western Allies as occupiers than Soviet Russia.

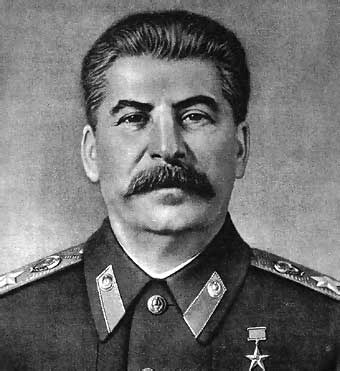

The high casualty rate was also a result of Soviet haste. Stalin had delayed the assault on Berlin because he wanted Soviet forces to be well-prepared to face the expected fierce Nazi resistance. On 1 April 1945 the Generalissimo summoned his top commanders to the Kremlin and made clear it was imperative for the Red Army to get to Berlin before the Americans or the British. Though he had originally promised the capture of Berlin to Marshal Zhukov, Stalin now split the command of the assault between Zhukov, Konev and Rokossovsky, telling them that ‘Whoever breaks in first takes Berlin’. Giving them two weeks, Stalin sparked a race between his senior commanders to capture the German capital. The commander of the unit which raised the ‘Victory Banner’ over the Reichstag would be made a Hero of the Soviet Union.

The race for the Reichstag

Stalin was initially hesitant about a dash for Berlin. At Yalta in February 1945 he had followed a ‘cooperative policy’ with the Western Allies that could benefit the Soviet Union, and might be threatened by a unilateral seizure of Berlin.

For the commanders and soldiers of the Red Army, however, the capture of the Reichstag was a symbol of their sacrifice and final triumph in the war with Nazi Germany. The letters home of ordinary soldiers testify to this thirst for revenge and glory, with the target of the Reichstag often prominent in their thoughts. The Eastern campaign of the Second World War fought between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia had been incredibly destructive of life and country; it was four times the scale of the conflict on the Western Front. The Nazi invasion and Soviet counter-offensive resulted in over 23m Soviet military and civilian deaths. Berlin would be theirs by right of suffering and not just conquest.

The race for the bomb?

Anthony Beevor has argued that the race for Berlin was an episode in Stalin’s quest for an atomic bomb. Soviet spies had informed Stalin of the progress of the Anglo-American-Canadian Manhattan Project. The Soviet programme, Operation Borodino, was far behind. The US had so far given only token supplies of the crucial material uranium oxide to the Soviets - in the hope of finding out what they were up to - and intended, with the British, to establish a post-war monopoly on the world’s supplies of atomic material. Stalin was determined to capture the expertise and atomic supplies of the German nuclear research centre, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, situated to the southwest of Berlin. But although the Red Army managed to capture successfully the facilities and three tons of uranium oxide, which gave a much needed boost to Stalin’s atomic bomb programme, the Western Allies made off with the expertise.

The Soviet view of the European endgame

Stalin saw in a conquered Germany and Eastern Europe the opportunity to redress the immense human and material losses of the war: a source of physical and financial reparation, labour and the markets necessary for reconstruction of the Soviet economy and society. But Stalin mistrusted the territorial, political and commercial ambitions of the United States and Britain. Their aim, he believed, was to meet the Red Army as far West as possible, occupying territory in the agreed post-war Soviet zone. British and American troops had crossed the Rhine, having taken advantage of the German failure to blow up a railway bridge spanning the river at Remagen, and Stalin feared that they would get to Berlin before the Red Army. He also feared, wrongly, a separate armistice between the Western Allies and Germany. Stalin’s mistrust was exacerbated by the death of President Franklin Roosevelt on 12 April 1945: Roosevelt’s successor, Harry S. Truman, had said in 1941 that the Nazis and Soviets should be left to kill off one another. Stalin decided, therefore, to revive earlier Soviet plans to take Berlin. In fact, Truman, initially at least, would continue what he judged to be Roosevelt’s strategy. The contribution of the Western Allies to the final assault on Berlin was limited to bombing the city and German fuel supplies until the Red Army entered the capital on 20-21 April.

The US view of the European endgame

Eisenhower therefore resisted British calls to get to Berlin before the Russians: he saw no need to suffer the heavy casualties anticipated or to antagonise Stalin. Anyway, he reasoned, it had been agreed that the German capital would be in the Soviet sphere of influence. Eisenhower perhaps underestimated Stalin’s determination to take Berlin and capture the German nuclear research programme. The US Commander in Chief decided to stick to his own plan of a general advance across the Rhine and the surrounding of the Ruhr. With the approval of Washington, but to the dismay of London, he directed the main American thrust eastwards towards Saxony - where US and Red Army soldiers shook hands on the Elbe at Torgau 25 April - and south to take what he wrongly believed would be the final Nazi redoubt in the Bavarian and Austrian Alps. With little confidence that British forces could reach Berlin before the Russians, as a concession to the British Eisenhower ordered them to push on to the Danish border and advance along the north German coast.

The British view of the European endgame

Though neither content with a Red Army capture of Berlin nor sanguine about post-war Soviet ambitions, the British were in no position to challenge the Russians in a ‘race for the Reichstag’. If US policy had been to get there first, Western Allied forces might have given the Red Army a run for their money, but in this final stage of the European conflict American attention was fixed firmly on the Far Eastern war. For the Soviet Union, reaching Berlin first was both a symbolic act and a practical pre-emptive strike. Stalin was determined that it must be Red Army soldiers who overcame the ferocious last stand of Nazi Germany and planted their Victory Banner in the burning ruins of the Reichstag. The force of the Soviet leader’s determination, and the Russian desire for revenge at the end of a terrible conflict, was to prove an ominous portent for the unfolding story of post-war Europe. But in late April and early May 1945, most people just wanted the war in Europe to be over.

Suggestions for further reading:

Anthony Beevor, Berlin: The Downfall 1945 (Penguin Books, 2002)

John Erickson, Road to Berlin: Stalin’s War with Germany Volume II (Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1983)

Gill Bennet (ed), The End of the War in Europe 1945 (HMSO, 1996)

David Stafford, Endgame 1945: Victory, Retribution, Liberation (Little, Brown, 2007)

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.

1 comment

Comment by starla posted on

amazing story