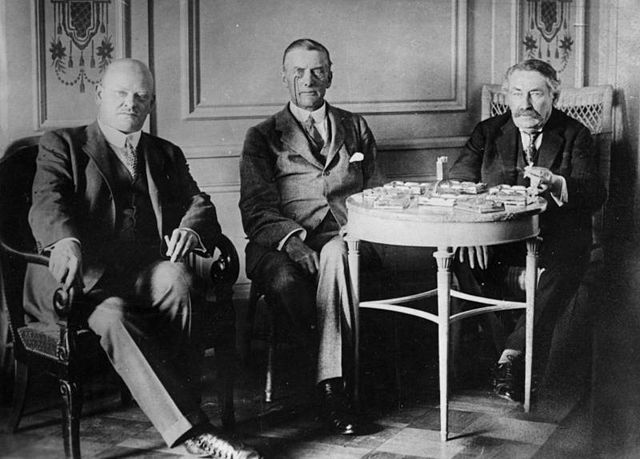

1 December 2015 marks the 90th anniversary of the formal signing of the Locarno Treaties at the Foreign Office in London. Named after the town in Switzerland where the treaties had been negotiated a few months earlier, their aim was to bring peace and security to Europe. However, as the British diplomat Harold Nicholson later wrote: ‘The Heavenly alchemy of the Locarno spirit, the triumphant splendour of those autumn days, did not prove of long endurance.’ The success of these negotiations, however fleeting, owed much to the good rapport between Foreign Ministers who would dominate European diplomacy for the rest of the 1920s: Austen Chamberlain (United Kingdom), Aristide Briand (France) and Gustav Stresemann (Germany).

Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R03618 @WikiCommons

Europe after the First World War was an unsettled place. Germany was still aggrieved by the Treaty of Versailles and wanted revisions. However, the Germans were still excluded from many diplomatic negotiations. France, Belgium, Czechoslovakia and Poland, on the other hand, feared a revival of German military power and wanted their borders to be guaranteed against a future German invasion. French anxieties about a resurgent Germany, greater in population size and industrial capacity, were heightened by a settlement of the reparations question through what was known as the Dawes Plan (1924).

In 1923 and 1924 two efforts to secure the peace through the League of Nations failed. First to fail was the Draft Treaty of Mutual Assistance (1923) which would have bound all member states to assist a victim of aggression. Second to fail was the Geneva Protocol for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes (1924), which aimed to tie together security and disarmament with compulsory arbitration of disputes. Both were rejected by the British government following objections to obligations of military assistance and economic sanctions.

The diplomatic puzzle of European security therefore remained unsolved. France wanted a formal military alliance with Britain, hoping to avoid the uncertainties of British commitment to securing peace on the continent in the years leading to the First World War. However, the British were uneasy about extending existing defence commitments and instead wanted disarmament, hoping to avoid an arms race which many argued had led to the First World War.

On 9 February 1925, the German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann proposed a mutual guarantee for the permanence of the Franco-German frontier and the demilitarized zone of the Rhineland. After initially hesitating, the Francophile British Foreign Secretary Austen Chamberlain, supported the idea as a way to allay French fears of a resurgent Germany. The essence of this Pact of Mutual Guarantee was that if one country violated another’s agreed borders, neutral countries would enforce them militarily. The guarantee was subsequently broadened to include the German border with Belgium.

Through the summer of 1925 the shape of the agreement was thrashed out. Still, much diplomatic haggling lay ahead of the statesmen as they gathered at Locarno on the northern tip of Lake Maggiore in southern Switzerland to finalize the agreement. The site was chosen by Stresemann for its neutrality, relative freedom from press scrutiny and proximity to Italy should Benito Mussolini, the Italian Prime Minister, wish to join the party to bask in the glory of a successful outcome (which he duly did). The location worked its magic as strolls about town, luncheons and even a boating excursion saw the resolution of the remaining sticking points. On 16 October, Chamberlain’s sixty-second birthday (a coincidence deliberately engineered by the British delegation), they initialled the agreement at the Locarno town hall.

On Chamberlain’s invitation, the Locarno delegations reconvened on 1 December 1925 in London for a formal signing in the Foreign Office’s Reception Suite which was later renamed the Locarno Suite. The recent death of Queen Alexandra could not dampen the jubilation at what many hailed as the beginning of ‘the Great Peace’. Indeed, in 1926 the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded jointly to Stresemann and Briand for their efforts on Locarno. The previous year it had been shared between Chamberlain for his promotion of the treaty and the American Charles Dawes for his work on the reparations settlement.

The Locarno Treaties included arbitration treaties between Germany and France, Belgium, Poland and Czechoslovakia. However, there was to be no ‘Eastern Locarno’. Instead there were new treaties of mutual assistance between France and Poland and France and Czechoslovakia to make up for the failure to obtain any German guarantee of its eastern frontiers. Most importantly, the Rhineland Pact obliged Britain and Italy to act against any violation of the existing borders between Belgium and Germany, and France and Germany and provided for arbitration to settle future disputes. These five Rhineland powers foreswore war with each other (except that France would aid Poland in the event of German aggression). Once Germany joined the League of Nations (as it did in 1926) violations of this pact and subsequent arbitration procedures would be referred to the League Council.

The big winner of the Locarno negotiations and Treaties was Germany which was once again a respected power. Germany had not only prevented the formation of an alliance directed against itself but had gained from important concessions on the terms of the Versailles Treaty such as on disarmament, reparations, and the threat of occupation.

The big losers at Locarno were France and its east European allies. France lost its power to enforce the Versailles settlement. If French troops again marched into the Ruhr, as they had done in 1923, Britain and Italy would be called on to come the Germany’s aid against France. France could do little if Germany did what the French most feared, defaulted on reparations and its commitment to disarmament. Poland and Czechoslovakia ended up with no German guarantee of their territorial gains from the peace treaty. Briand had got what he could, including, crucially for him, a British guarantee of the frontiers and peace of Europe.

Britain emerged from Locarno holding the balance of peace in Europe, but its ability to guarantee the security of the Rhine frontier was minimal. Its army was an imperial one, scattered across the globe. The force available for intervention on the European continent, much as before the First World War, was too small to cope with the sophistication and speed of modern warfare. However, Britain’s naval and financial muscle was enough for now to dissuade the French and Germans from conflict.

However, Chamberlain’s fervent desire for peace brought harmony only in the short term. The so-called ‘Spirit of Locarno’ never truly held. Despite Stresemann’s triumph, the Locarno guarantee of Germany’s Western Frontier only fuelled its growing revanchism and revisionism. At the same time the Locarno treaties undermined the League of Nations. With the Wall Street Crash in 1929 and the ensuing global economic depression, the optimism and sense of security which characterised the latter half of the 1920s ended. But it is important to remember that for a period there was a global belief that future wars could be prevented and conflicts could be resolved by peaceful, diplomatic means.

Suggestions for further reading:

Locarno 1925: The Treaty, the Spirit and the Suite

The Locarno Suite: ‘Drawing room for the Nation’

Sally Marks, The Illusion of Peace: International Relations in Europe, 1918-1933 (Basingstoke: 2003)

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.

1 comment

Comment by Robert Denemark posted on

I understand that the Foreign Office instituted a new Bureau for the Conclusion of Multilateral Treaties in 1923 to help foster just such agreements. I cannot find any source on this - information on the historical structure of the Foreign Office is hard to find. Might anyone be able to confirm the creation of this Bureau at this time and/or help me find a source on the structure of the FO? It would be greatly appreciated.